This post was written by Isabel Parkinson, who studies German & Philosophy at Worcester College.

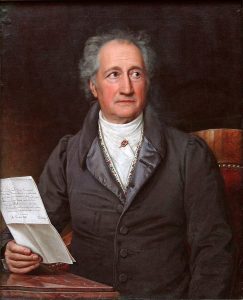

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe was born, rather poetically, on a summer’s day in Frankfurt in 1749 just as the church bells were striking noon. In true sensitive-artist style he studied law as a young man and detested it, preferring to attend poetry lectures instead and write Baroque-style verse for his lover. Goethe became a literary celebrity at just twenty-five when he wrote Die Leiden des jungen Werthers – a quite beautiful story that’s not only unchallenging enough to be read for pleasure, but has been so excellently translated that no knowledge of German is required. It’s achingly melancholy and endearingly optimistic in equal measure with a core of reverent, self-sacrificial, and occasionally obsessive love; the young hero Werther is so desperately infatuated with Lotte that he sends his servant to her house when he himself cannot visit, just to have someone in his home who has seen her.

Werther made Goethe an overnight success, and by the 1790s he was collaborating and communicating with the other major player in the German literature scene, Friedrich Schiller. In 1809 Goethe published his third novel, Elective Affinities. It is written in prose, rather than in the epistolary style of Werther and is a similarly excellent story, with not so much a love triangle as a love square or maybe even a pentagon.

Goethe turned his hand to many things – politics, science, prose – and his epic reworking of the classic legend Faust is an example of his dabbling in the closet drama genre. Part One is closely connected to the original famous legend, while Part Two – published in 1832, the year of Goethe’s death – pushes the story and the soul wager to its conclusion. The rich detail and sheer length of Goethe’s Faust may unfairly paint it as an impenetrable work; these misconceptions hide a vividly imagined and often quite humorous tale. It is true that one can make much of the religious, moral, and philosophical questions, but they are balanced with lighter touches such as a shape-shifting poodle and Mephistopheles accompanying Faust on a double date through a garden – and what Oxford student can fail to identify with the dissatisfied academic who trades his soul for knowledge and pleasure?