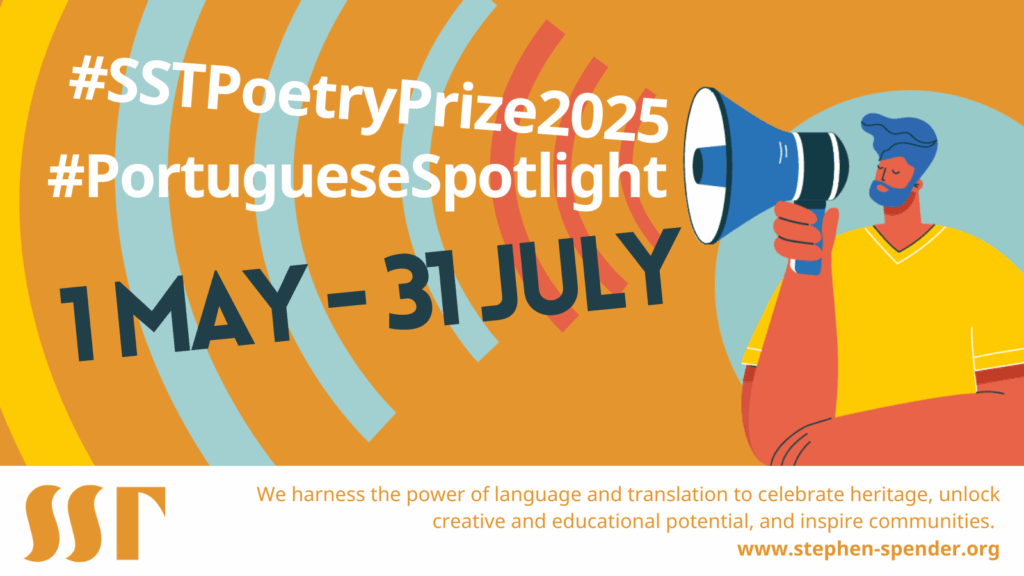

This week, we pass over to our friends at the Stephen Spender Trust to tell us about their 2023 prize for poetry in translation.

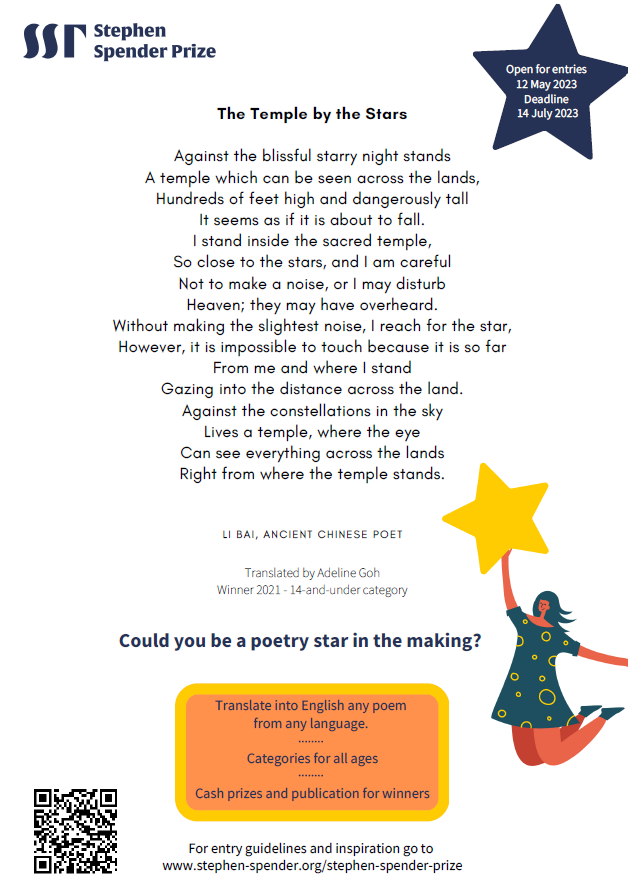

Translate ANY poem from ANY language into English, and win publication and cash prizes! Language lovers and budding poets of all ages are warmly invited to take part in the Stephen Spender Prize for poetry in translation, open to adults aged 19+ from all over the world, as well as to individual young people and school pupils in the UK and Ireland and students at British Schools Overseas.

For 2023 there will also be a special language focus with the Ukrainian Spotlight strand, open to all young people in the UK and Ireland aged 18 and under.

The deadline to submit entries is 14th July.

Details:

Entrants are invited to submit an English translation of a published poem from any language, ancient or modern, together with a commentary of no more than 300 words. The translation should be max. 60 lines (extracts are accepted). All forms and genres are welcome, including texts from rap, spoken word and slam poetry. We also welcome translations from sign language.

Prize strands:

- International Open Entry (NEW FOR 2023) – For adults aged 19+ from all over the world.

- Individual Youth Entry – For individual young people in the UK and Ireland or attending British schools overseas. Two age categories: 14-and-under; 18-and-under.

- Schools Laureate Prize (NEW FOR 2023) – For teachers submitting on behalf of their students, open to schools in the UK and Ireland and British schools overseas. Four categories for pupils from KS1 to KS5.

- Ukrainian Spotlight (NEW FOR 2023) – For young people in the UK and Ireland or at British schools overseas. Entries can be submitted individually or by teachers on behalf of students. Three age categories: KS1-2, KS3-4 and KS5.

- Teacher Laureate Prize (NEW FOR 2023) – Free to enter for all teachers at schools that have entered pupils for the Schools Laureate or Ukrainian Spotlight strands.

Judges:

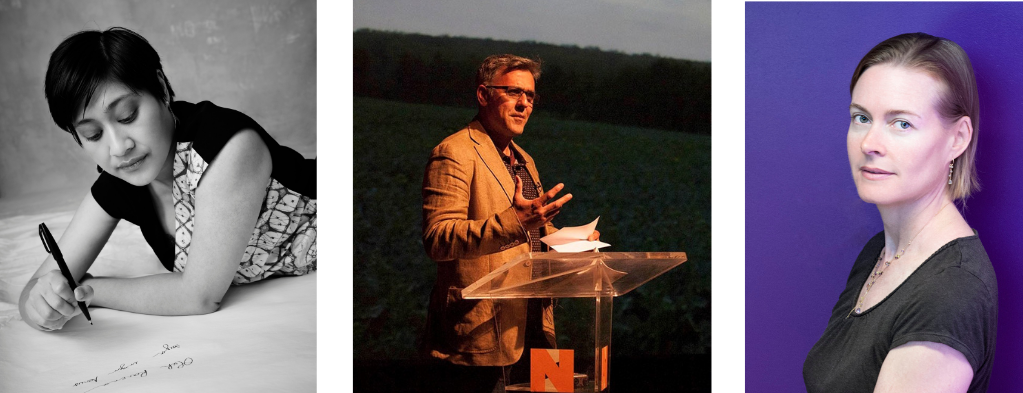

Open category: Taher Adel, Jennifer Wong, Samantha Schnee

Youth categories (Individual Youth Entry and Schools Laureate Prize): Keith Jarrett

Ukrainian Spotlight: Nina Murray

Prizes:

- Open Entry: £1000 (1st), £500 (2nd), £250 (3rd)

- Individual Youth Entry, Schools Laureate Prize and Ukrainian Spotlight: Cash prizes of up to £100 for the winners in each age category.

- Teacher Laureate Prize: Annual print subscription to Modern Poetry in Translation for the winning teacher, plus a Stephen Spender Prize workshop for their school during the next academic year.

All winners will have their translations published in our 2023 prize booklet and will be invited to participate in our livestreamed awards ceremony in the autumn. The winner of the Open category will also be published in Modern Poetry in Translation.

In each age category we will additionally reward three Highly Commended entrants and up to 30 Commendees, as well as three special First-Time Entrant Commendations in the Open category.

Entry Fee:

Open category: £10 per translated poem, or £5 per additional poem in the same submission.

Youth and teacher categories: Free

Further details:

Full information on how to enter can be found on the Stephen Spender Prize homepage and the different category subpages.

For a wealth of poetry translation inspiration, including advice for those trying poetry translation for the first-time, explore our Guide to Poetry Translation for Newcomers, the archive of tutorials and testimonials on the Stephen Spender Trust YouTube channel, and the multilingual bank of suggested poems for translation in our Prize Resources hub.

Good luck to all entrants!