This week’s blog post is written by one of our wonderful student ambassadors, a finalist in French and Spanish. Enjoy!

Before coming to Oxford, if you asked me about feminism, I wouldn’t have been able to tell you a lot other than about the suffragette movement and movements in the 1970s and 80s. However, one of the most rewarding and unexpected things that I have discovered since studying at Oxford is that feminism goes a lot further back than I had ever thought.

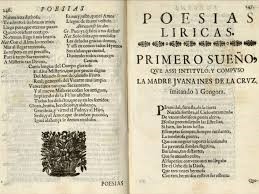

As part of my degree in Spanish, I had the opportunity to choose an ‘author paper’ that I would study over my second and final year. This is where you pick two authors and get to know a variety of their works in depth. Having enjoyed studying El médico de su honra by Calderón (a celebrated Spanish playwright) in my first year, I decided to pick a paper which focuses on the golden age (siglo de oro). I continued my studies on Calderón however, I was delighted to find that there was a female author on the syllabus (which is largely male-dominated as a result of contemporary attitudes of the time): Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. Although her works are known to provide some challenges with sentence structure and philosophy, I can firmly say that I am glad I took these challenges on.

Sor Juana was born in Mexico and had a desire to learn from a young age. As a result of the misogynistic attitudes of the time, she was unable to attend school. Despite this, she begged her mother to attend but disguised as a male student yet it wasn’t enough. Sor Juana was educated at home and during that time, she learnt how to read and write in Latin by the age of three and in Nahuatl (an Aztec language), she became well-versed in philosophy and wrote an array of poems.

Sor Juana later entered the monastery of the Hieronymite nuns which allowed her to pursue her studies with few limitations. During that time, she amassed a huge collection of books and was supported by the Viceroy and Vicereine of New Spain. The Vicereine Maria Luisa Manrique de Lara y Gonzága, Countess of Paredes was a recurring subject of her love poetry.

One of Sor Juana’s most famous poems ‘Hombres Necios’ (You foolish men) was written in the 1680s. This poem is one of my firm favourites! Published in a society that was extremely patriarchal, this poem criticises the double standards that men imposed on women and advocates the need for women to have more agency in their day-to-day lives. These double standards affected her reputation, her (sexual) freedom as well as her prospects as she would be left in situations that she could not control.

To illustrate her case, Sor Juana makes a strong argument for how double standards imposed on women aren’t just a problem of her time. Through comparing Thaïs (an independent, educated and sexually free woman who often accompanied Alexander the Great) to Lucretia (a woman who was so committed to fidelity to her husband that she killed herself after being abused by another man), Sor Juana demonstrates how there is a double expectation placed on women: they are expected to be sexually free like Thaïs before and then should completely change and be like Lucretia after entering a relationship with a man.

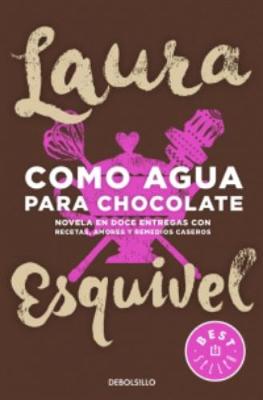

Whilst I have only mentioned one of Sor Juana’s poems, there are so many others that I could have delved into! For anyone who wants to further their interest in women’s writing or feminist works, I would definitely recommend Sor Juana (even if you are not studying Spanish!). There are many accessible English translations of her poetry and works available which also explore other themes such as education, love and philosophy. If you want to learn more about a subject area in general, there are so many beautiful opportunities to do so through literature. Whether it is medieval literature, seventeenth century plays or modern day poetry, there is bound to be a topic or genre that will fascinate you. Whatever the language, there is something for everyone!