This post was written by Kate Osment, a first-year student in German at St Anne’s College. Kate tells us a little more about studying German at Oxford and why Marx is still relevant today.

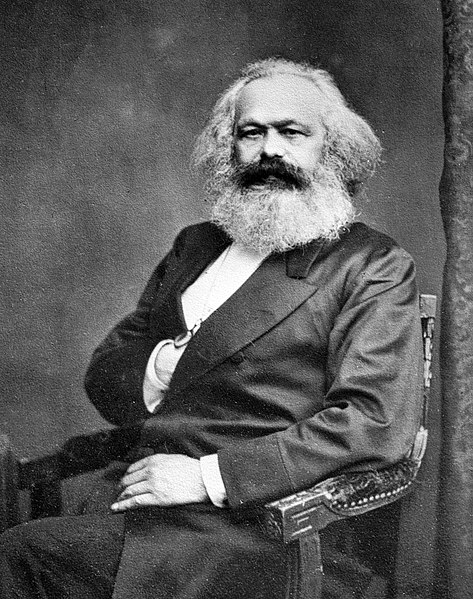

One of my favourite things about studying German at Oxford is the philosophy module in Hilary and Trinity (Easter and summer) terms. Over the course of eight weeks, we dissect the writings of famous German-speaking philosophers like Kant, Nietzsche, Freud (yes, he came up with more than the Oedipus complex), and of course Marx and Engels, looking at their arguments and the rhetorical devices they make them with. It’s challenging and fascinating generally, but out of these thinkers, the one who’s intrigued me most is Marx. Revered and reviled in similar measure, he’s worth reading because of the massive impact his ideas had on international 20th-century politics as well as the fact (which I think gets overlooked too often) that he’s just such a good writer!

Much of modern distaste for Marxism comes from a misunderstanding of what it actually is, so I’ll take the time here to say that Soviet Russia was Marxist in name only. Although a ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’ is widely seen as a Marxist goal, Marx believed this was only a step on the way to the perfect society, in which there’d be no social class distinctions – hence no class conflict – and no state. He thought there’d be no need for one, as he saw governance and law as an expression of the morality of the ruling bourgeoisie, forcibly imposed on the majority. The proletariat would – could – not rule in this way, because they’re the vast majority, so their interests are those of humanity collectively.

Marx argued that communism wasn’t just desirable, it was bound to happen. This stems from his theory of historical materialism, which Engels called his friend’s greatest ‘scientific discovery’. The argument is that all developments in human culture are driven by development of the forces of production. ‘The hand mill gives you society with the feudal lord, the steam mill society with the industrial capitalist.’ Capitalism only replaced feudalism because technological development made feudal society, with its guilds and protectionism, untenable. Communism would likewise replace capitalism because ever-more frequent crises of over-production would eventually drive profit down to nothing. Human history’s a story of class conflict caused by this evolution of productive forces, Marx believed, and because capitalism needs this evolution, the bourgeoisie will bring about their own destruction.

Of course, over-production doesn’t seem to lead to capitalist profits falling, and an accurate description of historical materialism is as a philosophical, not scientific, theory. But an end to bourgeois rule must’ve seemed possible in the 1840s when Marx and Engels wrote Das kommunistische Manifest, the same decade as Vormärz (the German workers’ revolution of 1848). And a world in which ‘the free development of each is a condition for the free development of all’ would certainly be preferable to one where six-year-olds work with dangerous machinery for 11 hours a day. Plus, the only thing that’s changed about that state of affairs is that it doesn’t happen in Western Europe any more. Anti-capitalist critiques remain necessary.

(If you’re interested in reading more about Marxism, I’d recommend Marx: A Very Short Introduction by Peter Singer, Why Read Marx Today? By Jonathan Wolff, and All That Is Solid Melts Into Air by Marshall Berman. And Naomi Klein’s No Logo is an invaluable critique of capitalism at the turn of the millennium.)