Seb Dows-Miller, an MSt student at Merton College, introduces some of the intriguing beasts he has encountered in the medieval Bestiary which is held by his College library.

When was the last time you tried to draw a lion? How did it go? It’s definitely not easy!

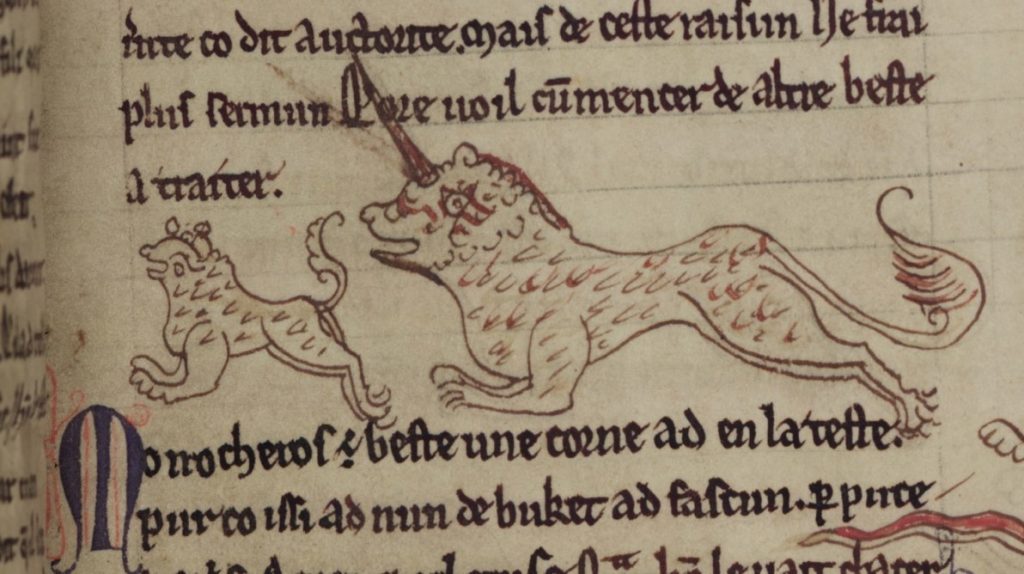

Now imagine you’re a medieval monk or nun, working in a dimly lit library with not much other than a candle to light up your work. You’ve been asked to draw pictures to accompany a bestiary, a medieval text that talks about the behaviours of different animals, many of which live in far-off lands or don’t exist at all.

You’ve never seen a lion, nor has anyone you’ve ever met, and the only clues you have about what they look like are drawings by other monks and nuns, who don’t really know what a lion looks like either. Do you think your drawing would be any good?

We actually have examples of drawings done in conditions like these. Manuscript 249 in the library of Merton College, written in a mixture of Latin and Anglo-Norman (a dialect of French that was spoken in England after 1066), contains one of only three surviving copies of a bestiary by the poet Phillippe de Thaon.

The manuscript has been at Merton since 1374, and in it there are close to 50 line drawings containing all sorts of animals.

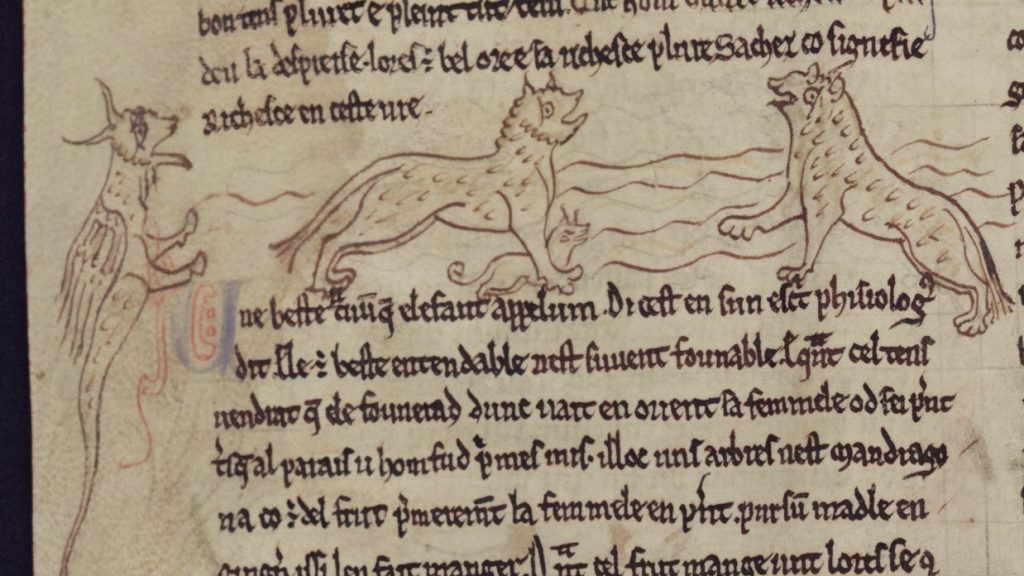

The image below, for example, shows a lion hunting a zebra, and was almost certainly drawn by somebody who hadn’t seen either animal before, but it’s still pretty good!

Some of the drawings are less successful… The one below depicts the ‘cetus’, a mythical creature that has been written about since Classical times, generally assumed to be modelled on a whale. Clearly nobody had ever got close enough to realise whales don’t have scales!

Among the mythical beasts in the bestiary, we also find a ‘monocheros’ (unicorn). While we usually think of the unicorn as being very similar to a horse, according to Phillippe de Thaon and those who copied the text it was actually closer to a ‘buket’ (goat)!

What was the purpose of this text? Nowadays we have all sorts of books and TV programmes talking about the behaviour of animals as we understand it, and so in that sense the bestiary isn’t too different to the way most of us think about wild animals today.

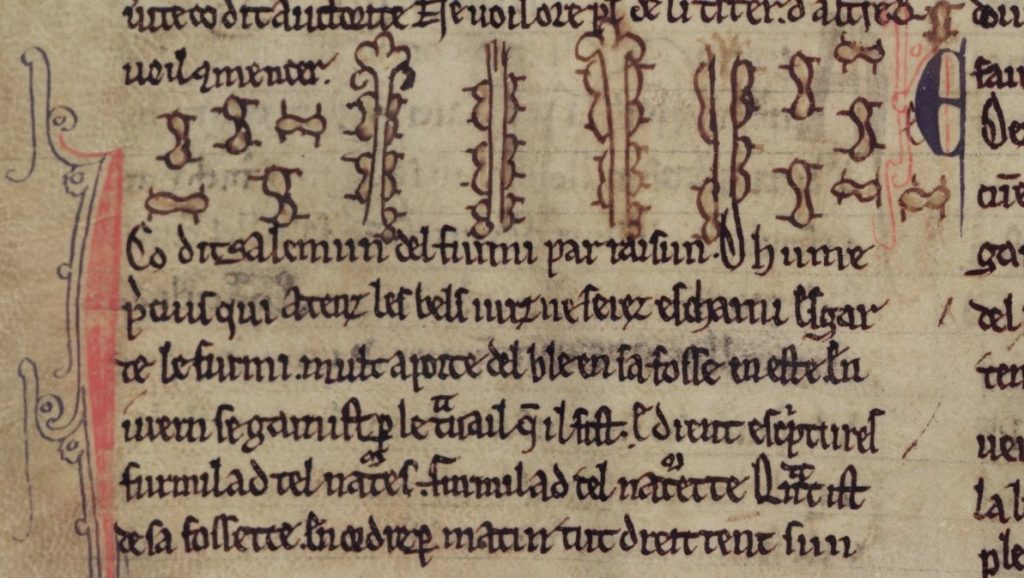

Unlike our modern approach, however, medieval bestiaries are usually quite religious in flavour. They talk a lot about what the behaviour of animals apparently tells us about the teachings of religious texts such as the Bible. The community spirit and self-sacrifice of ants, for example, is said to tell us a lot about the way in which Christian society should be organised.

So, did the readers of our bestiary only want to get down to the Christian message of the text? We can’t be too sure, but it was almost certainly more complicated than that. Whatever the texts themselves say, people reading and copying bestiaries probably wanted to find out more about the natural world just as much as they wanted to hear any religious messages.

Another important question is: who read this text? We can be sure that once it had arrived at the college, Merton’s copy was read primarily by men who were members of the college, but was this always the case? The text is dedicated to Eleanor of Aquitaine (1122-1204), wife of Henry II of England, and so there was at least one intended female reader!

The fact that this particular bestiary was written primarily in Anglo-Norman, rather than Latin, which is very unusual for this part of the Middle Ages, suggests that the text’s audience was probably quite broad, and may have included people who didn’t know how to read Latin. Just as we use books with pictures to teach children how to read, could bestiaries have been used to help teach medieval learners?

What’s going on here? The picture below shows an ibis eating (possibly) a snake, but the picture has been cut off at the bottom of the page. This probably doesn’t mean that the illustrator just ran out of space, but rather that someone later on, when putting a new binding on the manuscript, trimmed off the bottom of the page to make it fit.

Meanwhile, this poor onoscentaurs (centaur) has had the top of his head trimmed off! We see this a lot in medieval manuscripts, where later re-binders have cut off images or sometimes even text. The most recent re-binding of Merton MS 249 took place in the 17th century, so it could have happened then or even earlier.

This shows just how important it is to remember that manuscripts change over time. The manuscript didn’t stand still after its creation, with different generations of readers having different interpretations of what makes it valuable.

There’s so much more to discover in this manuscript, so why not have a look for yourself! The text is very difficult to read (although you might recognise certain words, even if you don’t speak French), but the pictures tell just as much of a story. You can also follow the misadventures of Merton’s beasts on Twitter: @MertonBeasts.

by Seb Dows-Miller

Images reproduced with the kind permission of the Warden and Fellows of Merton College, Oxford.