In this final post by Oxford students who were involved in judging this year’s Prix Goncourt, Ombline Damy (Hertford College) shares some thoughts on the four shortlisted novels.

The four novels that made it to the shortlist of the Prix Goncourt could not be more different from one another, in theme, writing style, tone, voice. The astounding diversity of the texts made our task as judges close to impossible.

The winner of the British Prix Goncourt, Djaïli Amadou Amal’s Les impatientes, interrogates the (elusive) virtue of patience within the context of the oppression of women in Sahel. Written in a simple, but certainly not simplistic, language, the author uses a polyphony of female voices to craft her powerful and harrowing narrative.

Also set in Africa, Maël Renouard’s L’historiographe du royaume explores the intricacies and challenges of life in the service of a king through its narrator and main character Abderrahmane Eljarib, who spends most of his life seeking, more or less successfully, the favour of Moroccan king Hassan II (1929-199).

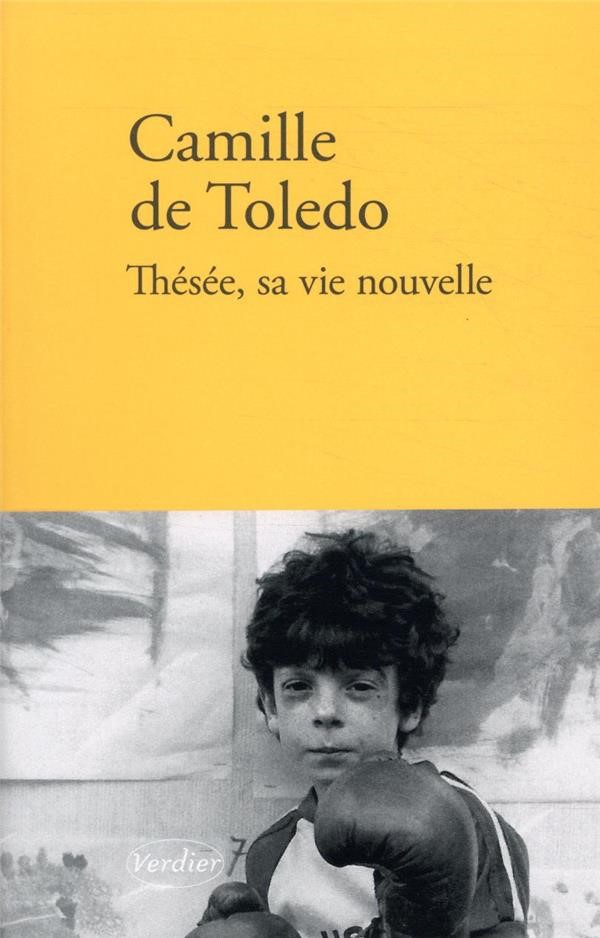

Moving away from the questions of political power and influence which dominate Les impatientes and L’historiographe du royaume, Camille de Toledo’s Thésée, sa vie nouvelle asks the haunting question of who commits the murder of a man who kills himself. And this man, we find out in the text, is none other than the writer and narrator’s own brother.

Contrasting with the autobiographical tone of Toledo’s text, the winner of the French Prix Goncourt, Hervé Le Tellier’s L’anomalie, is a thought-provoking page turner which skilfully interweaves a plethora of literary genres, in what seems to be, in the end, a sci-fi novel. It is a true challenge to talk about the book without giving away important plot twists, but hopefully I will not be revealing too much about the text when I write that it turns around the question of what would happen if the same plane were to land twice.

Faced with such disparate novels, how is one to choose which one of these four texts is the ‘best’ book? For choosing the ‘best’ book is, in the end, what the role of a literary prize judge is. ‘Best’ according to which standards? Enjoyment? Importance of the subject-matter? Literary and aesthetic qualities? Ultimately, then, as judges for the British Prix Goncourt, we have had to ask ourselves a million-dollar question: What makes for literary value?

If Les impatientes is the novel that won the British Prix Goncourt, there can be no doubt that the three other novels have something to teach us about literary value – and also that each of them is equally deserving of the literary prize itself. Hannah Hodges has written in more detail about Les impatientes in this blogpost.

What impressed me most about L’historiographe du royaume is the author’s capacity to borrow from, imitate and connect distinctive literary styles. Renouard indeed consciously uses the language of Louis Rouvroy de Saint-Simon, whose memoirs commented on and criticised the workings of Louis the fourteenth’s court in Versailles. Renouard does not, however, stop at transposing Saint-Simon’s voice in the context of Hassan II’s reign. He also adopts a Proustian rhythm, and copies the style of the One Thousand and One Nights. What emerges out of this virtuosic pastiche of literary models and references is a rich and carefully thought-through text, whose literary value lies precisely in its intertwining of disparate perspectives and styles in a coherent narrative.

Thésée, sa vie nouvelle is equally virtuosic, but for very different reasons. The narrative that Toledo crafts, investigating the reasons that led his brother to take his own life, is beautifully melancholic, and deeply touching. Toledo pays great attention to the aesthetics of the text on the page. With its use of images drawn from the author’s family albums, bold and italic text, and attention to detail, the text assumes the form of a book-long poem. Toledo’s story becomes the reader’s own, as one is drawn into the narrator’s uncovering of the successive traumas which shape his family’s history. I became acutely aware of my own attachment to the story when I thought I had accidentally thrown away the slip which was wrapped around the book. It’s just a slip, you might think, isn’t important. Believe me, I tried to reason myself in this way too. But, on the slip was a photo of Jérôme, the narrator’s deceased brother, as a child. Losing it made me feel as though I had erased him out of life once again. And, to be frank, I could not bear the thought of having done that. Such is the effect of Toledo’s elegy in memory of his dead brother.

Le Tellier’s L’anomalie could not be more different than Thésée, sa vie nouvelle. And yet, in its own way, this book is also astonishing. Le Tellier is an incredibly gifted engineer of literature. Setting himself a task, writing a novel which brings together different literary genres, he achieves just this. From one chapter to another, Le Tellier takes his reader from crime fiction to chick lit, from science fiction to realistic fiction. The speed with which he draws us into the world of each of his characters is extraordinary. Listening to him speak, we understand why: his characters are real to him; he has a true affection for some of them, a strong dislike for others. They simply exist. And the reader becomes utterly convinced of the same thing. It will be hard to forget Joanna, Slimboy, and Victor Miesel.

Les impatientes, L’historiographe du Royaume, Thésée, sa vie nouvelle, and L’anomalie, then, are each ‘best’ books. It’s a shame that we had to choose only one of them.

To read more about the process of judging the British Prix Goncourt, see Sophie Benbelaid’s blogpost here.

by Ombline Damy