posted by Kate Rees

2016 marks the fifth year of Oxford University’s French film competition, in which school pupils are invited to watch a selected French film, and write an essay or script re-imagining the ending. As last year, the competition was open to students across secondary school year groups, with a large number of entrants from pupils in years 7 and 8. We received almost 200 entries, from over 50 schools.

The judges were deeply impressed by the range and richness of responses to the two set films, both directed by Céline Sciamma: Tomboy (years 7-11) and Bande de filles (years 12-13). The winner in the younger age category was Sophie Benbelaid, who came up with a startling and creative interpretation as to the young Laure’s decision to act as a boy. (An extract from Sophie’s entry is below.) Runners-up in this category were Nano Quirke-Bakradze and Nikolas Thatte. Kate Lopez Woodward and Bridgette Dancel were highly commended; six more students received commendations (Roxy Francombe, Jamie Sims, Rose Tingey, Rachel Dick, Megan Bradley, Neave Reilly).

When judging the older age category, we were so taken with the overall standard of the entries that we decided to offer prizes to joint winners. Read an extract from Gurdip Ahluwalia’s imaginative French-language script here. George Jeffreys wrote and directed a filmed ending to Bande de filles, reflecting the tensions and energy of Sciamma’s own cinematography. In this category, Amy Jorgensen and Jack Butler received high commendations; four more pupils received commendations (Elena Albot, Clare Borradaile, Lucy Morgan and Isabelle Smith).

Rewritings of the end of Tomboy offered a rich tonal and emotional range, from the gentle and tender to the sudden and shocking. Laure was often seen as disturbed by uncertainty of her expression of her gender, running away and contemplating suicide; her mother too was often seen as angry and confused, and the mother’s pregnancy was seen to end traumatically in a number of entries. Other entries attempted to envisage a future for Laure in which she opted for gender realignment surgery. The strongest entries were those which captured something of the quiet intimacy of family life seen in Sciamma’s film, along with the childlike vision of the young Laure; various entries explored the relationship between the sisters in attentive and authentic ways.

In the older age category, there were some exceptional re-imaginings of the ending of Bande de filles. Many were written in French, and a number, too, opted to present their entries as a film script, imagining appropriate visual close-ups and musical insertions. Marieme/Vic was variously imagined accepting Abou’s offer, selling drugs, and sometimes being tempted into other criminal acts such as bank robbery; others opted for a more positive ending which saw her returning to study or coaching girls’ sports teams. As was the case with Tomboy, those entries which focused attention on the family relationships or on the interaction between the girls in the ‘bande’ tended to be particularly successful, introducing moments of tension, intimacy and credible dialogue.

The Medieval & Modern Languages Faculty congratulates all participants and expresses its gratitude to their teachers for supporting their entries. Particular thanks are offered to Routes into Languages for their generous support of the competition.

THE WINNERS

George Jeffreys:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vV-nSqtlMOg&feature=youtu.be

Gurdip Ahluwalia (extract):

SCENE 5

[A L’EXTERIEUR DE LA MAISON]

[MARIEME PREND QUELQUE CHOSE DE SA POCHE. LA CAMERA REVELE QU’ELLE TIENT A LA MAIN UN TEST DE GROSSESSE. LE TEST EST POSITIF. ELLE SOUPIRE ET ESSUIE LES LARMES DE SES YEUX]

SCENE 6

[ON REVIENT CHEZ ISMAEL. IL LIT LA LETTRE, CONFUS ET INQUIET. ON ENTEND LA VOIX DE MARIEME, QUI LIT LA LETTRE]

LA VOIX DE MARIEME : Ismaël, Je sais que je viens de dire que je t’épouserais, mais j’y ai pensé. Cette proximité à Djibril, la réputation d’être une putain. Ces deux problèmes signifient que je ne peux pas rester ici. Je risque d’être bloquée ici, sans avenir, sans possibilité. Je ne veux pas cette vie pour mes sœurs. J’ai vu la vie de ma mère. Elle travaille sans arrêt, elle n’a pas de motivation, elle, même, a peur de son propre fils. Si je reste ici avec toi ma vie sera la même. Et mes sœurs et moi, nous avons le droit de quelque chose de meilleur. Je veux faire quelque chose avec ma vie, je veux être quelqu’un, je veux montrer à mes sœurs qu’elles peuvent être les femmes qu’elles veulent être. Je ne peux pas t’épouser dans de telles circonstances. Peut-être si les choses étaient différentes. Mais elles ne le sont pas. Après tout, je ne peux que dire que je suis désolée. Je t’aimerai toujours, mais il faut que je fasse ce qui est meilleur pour les filles. Marième

[ISMAEL RESPIRE DE PLUS EN PLUS PENIBLEMENT, DEVENANT EN COLERE. IL DECHIRE LA LETTRE, EN PLEURANT. IL JETTE LES MORCEAUX DANS LA POUBELLE. IL Y A UN VASE SUR LA TELE. IL LE PREND AVEC VIOLENCE. LE VASE S’ECRASE CONTRE LE MUR]

SCENE 7

[A L’EXTERIEUR]

[MARIEME MET LE TEST DE GROSSESSE DANS LA POUBELLE. ELLE SOULEVE MINI ET LE SAC-A-DOS. ELLE PREND LA MAIN DE BEBE. SON PORTABLE SONNE. ON VOIT QUE C’EST LADY. APRES AVOIR ATTENDU QUELQUE MOMENTS ELLE SOUPIRE. MARIEME MET LE PORTABLE DANS LA POUBELLE AUSSI]

MARIEME (SOURIANT TRISTEMENT AUX FILLES) : Allons-y. Une nouvelle vie nous attend

FIN

Sophie Benbelaid (extract):

TOMBOY

“Lève-toi, tu dois t’habiller,”

Laure a respiré. Elle a entendu sa mère ouvre les rideaux. Fatigué, elle a tourné lentement sur son dos et a ouvert ses yeux – un œil et puis l’autre.

“Vite,” sa mère a dit encore, “va t’habiller.” Avec des pas chancelants, la jeune fille marchait à son armoire. Les portes étaient fermées.

“Pas là,”

Laure a fait demi-tour en entendant ces mots, “Quoi?” Laure a demandé avec une tonalité d’être encore demi-dormant.

“Tu t’habilleras dans cette robe,” et un vêtement en bleu était lancé sur les couverts du lit. La mère regardait sa fille très intensément pour sa réaction mais Laure restait tranquille; elle pensait au son rêve de la nuit avant. Elle s’est assise et a vu la robe qui était affalée sur son lit. Ses yeux se sont élargisses en choc.

“Non,” elle a murmuré, “Non, non, non!” Laure criait encore et encore et a couru à la porte où sa mère l’a empêché de s’évader. Elle a tenu sa fille au lit et elle y a mis.

“Arrête, Laure!” La mère a hurlé à sa tortillant fille. “Ça suffit, Laure! Arrête!”

Laure a senti les mains de sa mère sur ses épaules. Elle a arrêté de se bouger, mais elle s’est cachée son visage dans l’oreiller.

“Ça suffit, Laure,” sa mère a dit encore. Cependant, elle a eu une plus douce voix, cette fois. Elle est restée immergé dans son oreiller, mais elle écoutait. “Tu ne peux plus mentir à tes amis. Ce n’est pas juste pour eux.” Laure a commencé de se tortiller encore. “Ça m’est égal si tu veux t’habiller comme un garçon…” elle a caressé la tête de sa fille, “mais ils ont le droit de savoir la vérité.”

“Je n’irai n’importe où!” Laure a crié de façon agressive, “Tu ne peux pas me forcer,” elle a marmonné. “Je n’y irai,” La mère a soupiré, mais est restée près de la porte de la chambre. “Laisse-moi d’aller seule,” Laure a dit.

“Avec la robe?”

“Non, mais laisse-moi rendre visite à mes amis,” Sa mère a tiqué et a adopté un visage d’incrédulité. “Non,”

“Pourquoi?”

“Si tu iras avec la robe, tu peux aller. Mais si non…” le reste n’a pas besoin d’être dit à voix haute.

Sa mère a soupiré tristement. “Écoute, Laure, je sais que tu veux faire…”

“Je ne comprends pas que tu dis,”

“Oh, tu sais,” la mère a commencé de caresser sa fille encore, “mais tu ne veux pas l’accepter la vérité”. Laure n’a rien dit. “Laure, tu peux t’habiller comme lui, mais il ne reviendra jamais.”

Laure a fermé ses yeux et a pressé les serrés.

“Je ne veux pas parler au sujet de ça,”

“Et quand, alors?”

“Jamais,”

“Jamais? Ça c’est absolument ridicule. Est-ce que tu n’as pas écouté ce que la thérapeute a dit? À un moment, tu as besoin de parler au les choses qui-ce passent.”

“Oui, à un moment – pas en ce moment!”

Le silence que s’est ensuivi avait tant de tension que ni la fille ni la mère a bougé.

Petit à petit, les défenses de Laure se sont effondrées et, bientôt, Laure était en larmes. La mère a marché à sa fille et l’étreignit longtemps.

“Mon bébé, pleure,” Laure a fait de l’hyperventilation contre la poitrine de sa mère, qui a caressé sa fille dans un rythme stable pour la calmer. Même si ses yeux étaient fermés, Laure encore voyait l’accident devant elle.

![affiche-finale-agathe-212x300 [55473]](http://bookshelf.mml.ox.ac.uk/wp-uploads/2016/05/affiche-finale-agathe-212x300-55473.jpg)

![Pichet Marie Talbot [55474]](http://bookshelf.mml.ox.ac.uk/wp-uploads/2016/05/Pichet-Marie-Talbot-55474.jpg)

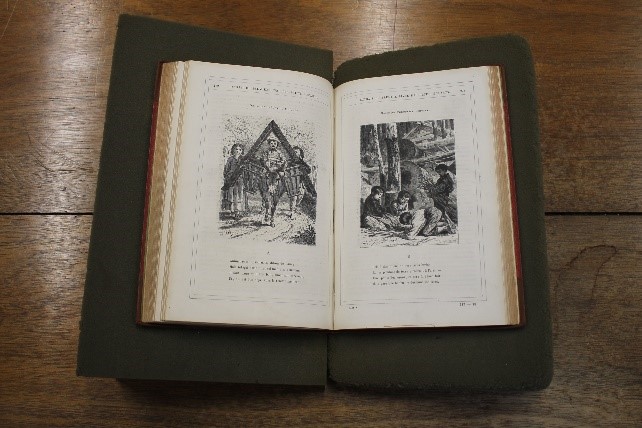

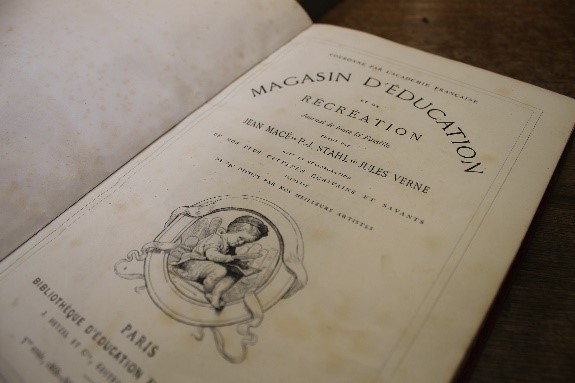

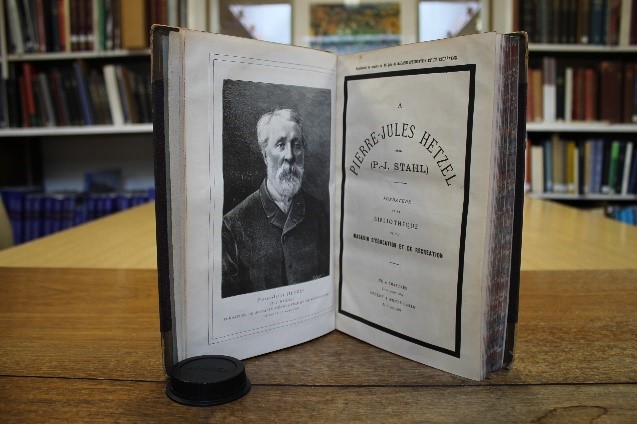

Typical title page of the Magasin d’éducation et de recreation, the era’s most popular children’s periodical.

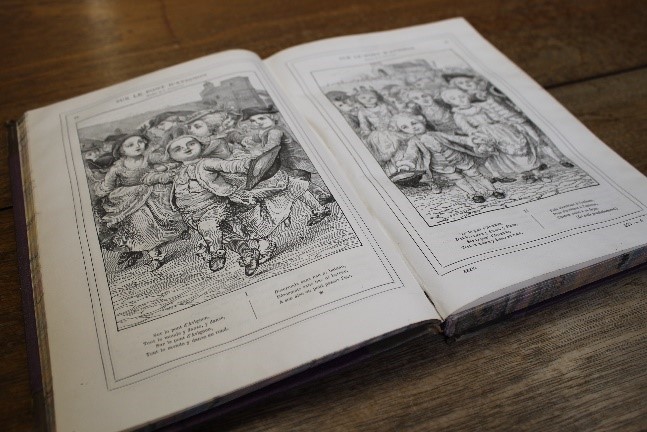

Typical title page of the Magasin d’éducation et de recreation, the era’s most popular children’s periodical. Remember this song from when you were a kid? They were teaching it in the 19th century too!

Remember this song from when you were a kid? They were teaching it in the 19th century too! Learn about France’s heritage in this segment called ‘Vues et monuments de France’.

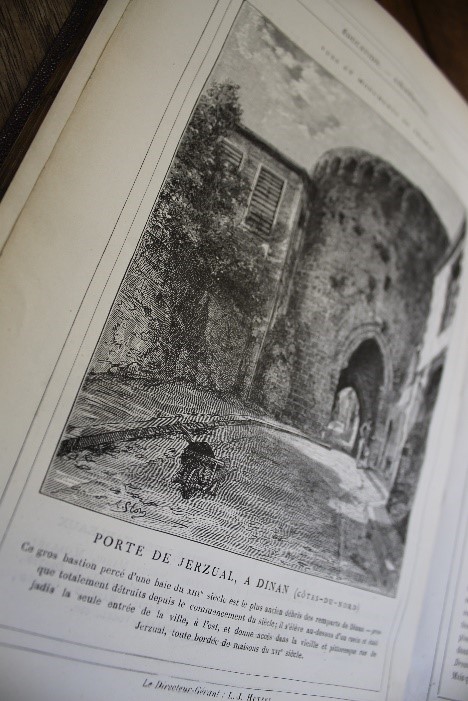

Learn about France’s heritage in this segment called ‘Vues et monuments de France’.

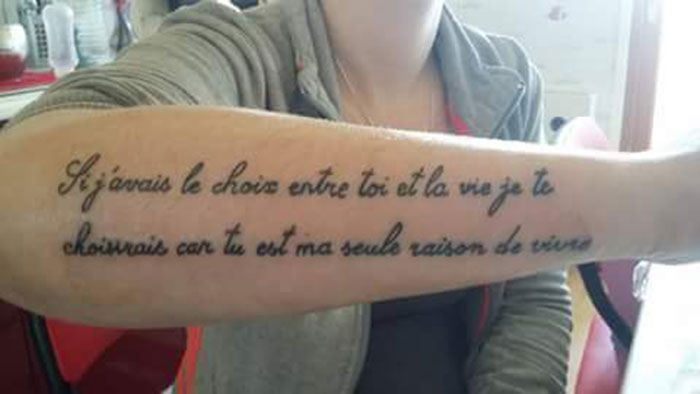

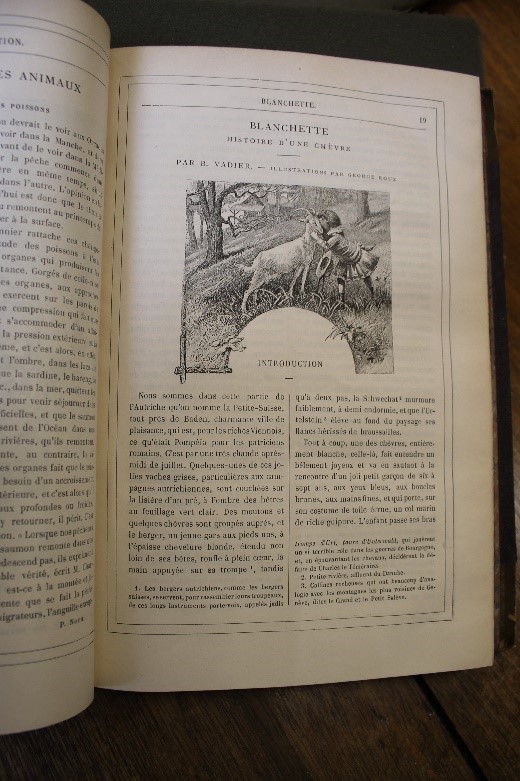

Notice the footnotes designed to help the young readers with new vocabulary.

Notice the footnotes designed to help the young readers with new vocabulary.