by Simon Kemp

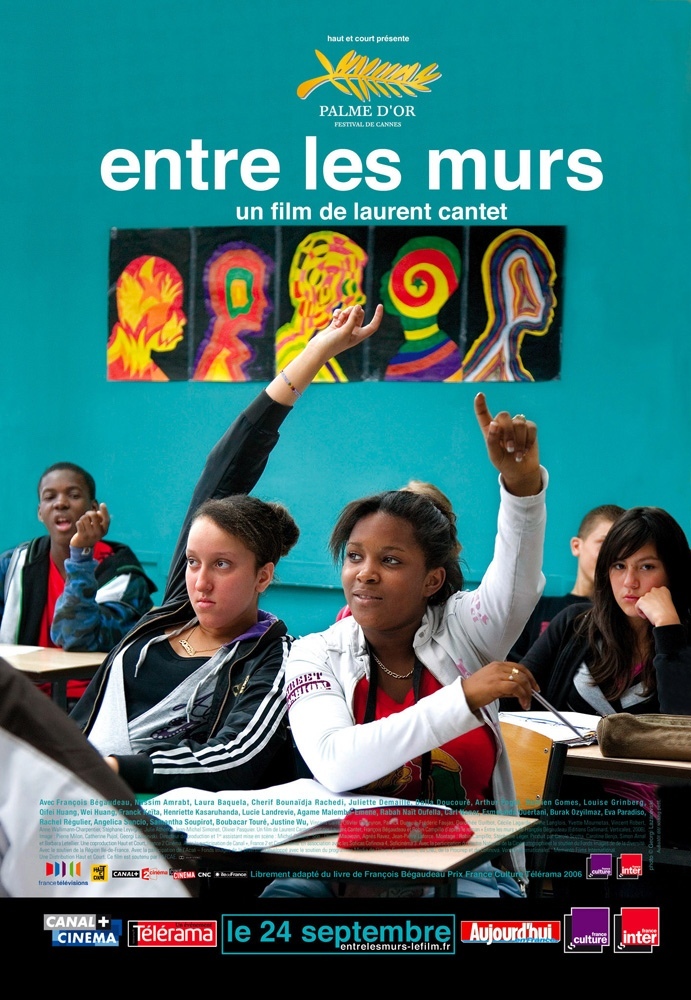

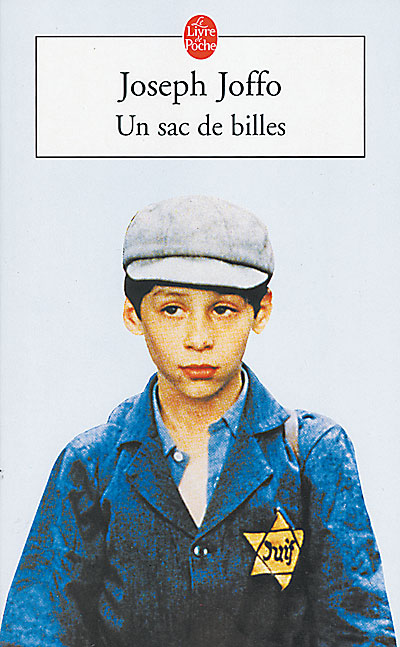

This is a post about the memoir Un sac de billes by Joseph Joffo, which you may encounter on the French A-level course.

A single marble that looks like a miniature Planet Earth…

a star-shaped piece of yellow cloth with the word ‘Juif’ written across it in stark black letters…

a canvas bag full of marbles with a shoelace as a drawstring…

…some of the objects we come across in the opening pages of Joseph Joffo’s Un Sac de billes take on outsized meaning for us as readers and for the two young protagonists who are about to go on the run from Nazi persecution in Occupied Paris. Among these objects are the musettes, the cloth bags in which the boys’ mother packs changes of clothes, soap and toothbrush and folded-up handkerchiefs on the evening that they are sent away from home:

Sur une chaise paillée, près de la porte, il y avait nos deux musettes, bien gonflées, avec du linge dedans, nos affaires de toilette, des mouchoirs pliés. (p. 35)

And out of all the things we see at the start of the story, it is the musette that returns to focus at the end. Joseph notes on his return to Paris:

J’ai toujours ma musette, je la porte avec plus de facilité qu’autrefois, j’ai grandi. (p. 228)

And the final image before the epilogue is of his reflection in the window of the family barber’s shop, full circle to the home he left years before:

Je me vois dans la vitrine avec ma musette.

C’est vrai, j’ai grandi. (p. 229)

A musette is a cloth bag with a shoulder strap, sometimes translated as satchel or haversack. It’s often associated with ordinary soldiers in the two World Wars, so kit-bag is another possible English rendering. Plus, if you fill it with oats and put the strap over a horse’s ears rather than over your shoulder, it can also be the French word for a nose-bag.

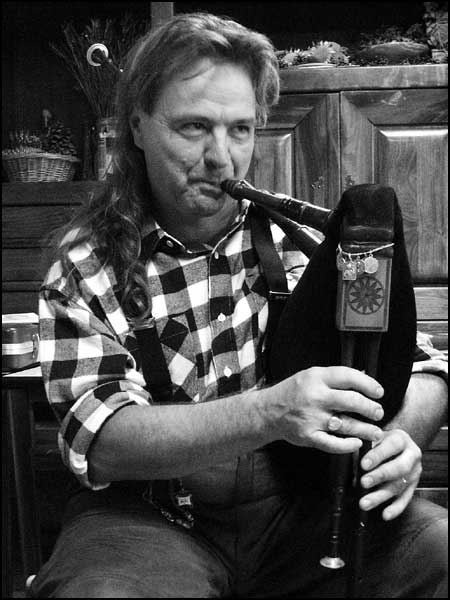

If it seems an odd word for a bag, that’s because it’s actually related to cornemuse, the French word for bagpipes, and musette can actually still mean a variety of French mini-bagpipes, as well as the sort of traditional French country music you might hear played on them – although these days you’d be more likely to hear it on an accordion. Even more oddly, the muse part of the words musette and cornemuse doesn’t seem to be related to musique/music at all: rather, it comes from museau/muzzle to refer to the face you have to make as you puff out your cheeks to inflate the bag while you play the pipes.

In the novel, the epilogue shows us why the musette is the thing Joffo has chosen to tie the start of the story to the end of it. Partly, it’s to show the literal circularity of Jo’s and Maurice’s journey, drawing our attention to the things that are the same (a boy with a bag standing in front of a barber shop window), and the things that are not (the child is now a young man, his father is no longer on the other side of the window). But as the epilogue makes clear, it’s also about another kind of circularity: the cycle of history repeating itself, generation after generation. The adult Joffo imagines what it would be like having to say the same thing to his own son as his father once said to him:

J’imagine que ce soir, à l’heure où il va pénétrer dans sa chambre, à côté de la mienne, je sois obligé de lui dire : « Mon petit gars, prends ta musette, voilà 50 000 francs (anciens) et tu vas partir. » Cela m’est arrivé, cela est arrivé a mon père et une joie sans bornes m’envahit en songeant que cela ne lui arrive pas. (p. 230)

But this ‘boundless joy’ is not the emotion on which the novel closes a few lines later. Rather, it’s on a note of foreboding that we end with an image of the musettes stored away in the attic, just in case:

Les musettes sont au grenier, elles y resteront toujours.

Peut-être… (p. 231)

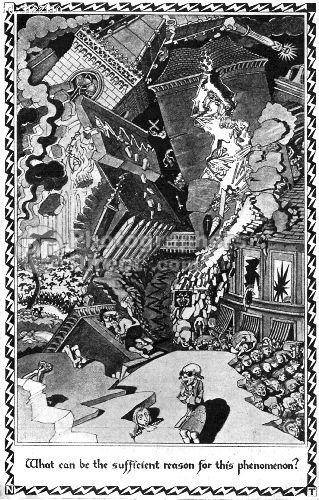

When Joffo’s father was forced to flee, we learned back at the start of the book, it was the violence of the anti-Jewish pogroms that forced him and his family from their home. That home was ‘un grand village au sud d’Odessa, Elysabethgrad en Bessarabie russe’.* The region of Bessarabie is part of modern-day Ukraine. As people once again flee from Odessa and the surrounding area in fear for their lives, while at the same time not one but two far-right candidates are prominent in this year’s French presidential election, Joffo’s work has never felt more timely than it does today.

* Joffo’s Elysabethgrad may or may not be today’s Kropyvnytskyi, which was called Elizabethgrad before 1924 and was the site of severe anti-Jewish violence during pogroms incited by the Russian Tsar in the early twentieth century. Kropyvnytskyi is a city rather than a village, however, and north of Odessa, so there may have been some confusions as the family tale was passed down the generations.

posted by Simon Kemp

posted by Simon Kemp