posted by Catriona Seth

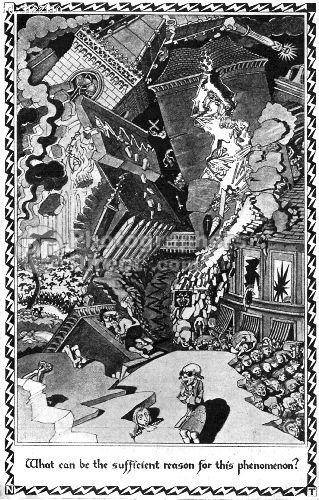

As the ship on which Candide is sailing nears Lisbon at the end of chapter 5, the sky becomes gloomy : ‘l’air s’obscurcit, les vents soufflèrent des quatre coins du monde, et le vaisseau fut assailli de la plus horrible tempête’. Candide, Pangloss and ‘ce brutal de matelot qui avait noyé le vertueux anabaptiste’ are the only ones on board who survive the storm and as they set foot in town, they feel the earth quake beneath their feet. Voltaire gives a graphic description of what happens. He was drawing on a recent historic event.

On November 1st 1755, Lisbon, at the time the third largest port in Europe, was hit by a terrible earthquake and tsunami. Much of the city was destroyed. In the following days, reports speaking of 100 000 deaths reached Geneva where Voltaire was living. These were certainly excessive, but they bear witness to the magnitude of the catastrophe, which is still considered to have been one of the deadliest earthquakes ever.

Voltaire was so distressed by the news that he set about writing a long poem. He called it Poème sur le désastre de Lisbonne ou Examen de cet axiome ‘Tout est bien’. He speaks of the innocent lives lost and can find no justification for why Lisbon should have been wiped off the face of the earth rather than similar cities like Paris or London.

‘Tout est bien’ refers to the doctrine of optimism: thinking that on the whole ‘tout va pour le mieux dans le meilleur des mondes possibles’, as the fictional Pangloss would say. Optimism was defended by the German philosopher Leibniz in his 1710 Theodicy, which justifies the existence of evil. He claimed the world could not have been better: to suggest it was imperfect, he believed, was like accusing God of not being up to the task he had set himself.

Following the earthquake, the philosophy of optimism no longer seemed defensible to someone like Voltaire. As he wrote to a correspondant on November 30th 1755, ‘Vous savez l’horrible événement de Lisbonne […] voilà un terrible argument contre l’optimisme.’

Candide was published four years after the terrible events, in 1759, and with the subtitle ‘ou l’optimisme’. In the book, the earthquake comes hot on the heels of a battle-scene. The slaughter is a manmade disaster. The earthquake is a natural one. You cannot blame anyone for it, in the way you might accuse a bellicose general of making his troops fight. The generous and virtuous Anabaptist drowns at the beginning of the episode set in and around Lisbon, whilst the wicked sailor survives. There is nothing moral about this. It clearly shows that all is not well.

During the whole of the ‘conte’, Candide, whose name means he is candid or naïve, is made to learn through experience (and through unlearning what Pangloss has erroneously taught him). Here he is shown that the force of nature cannot be controlled and that sometimes innocents die when criminals survive. This is an illustration of the fact that Pangloss’ philosophy (optimism) does not offer an acceptable explanation of the world. A number of other passages in the text show this in different ways, like the encounter with the ‘Nègre de Surinam’, a slave mutilated by his nasty owner.

Just after the earthquake in Candide, the Lisbon authorities organise an auto-da-fé: literally an ‘act of faith’, supposed to ward off any future disasters by torturing heretics. Voltaire is very sceptical of such actions. Since earthquakes have physical causes, there is no way that burning criminals will have any effect on their occurrence. The university of Coimbra’s supposed pronouncement that ‘le spectacle de quelques personnes brûlées à petit feu, en grande cérémonie, est un secret infaillible pour empêcher la terre de trembler’ is obviously ironic. Voltaire shows us (and this is a subject to which he frequently returned in his writings) that too often punishments do not fit the crime.

Even the severity of the alleged ‘crimes’ is called into question. One of the people put to death before Candide’s eyes has married his godchild’s godmother—an arcane rule of the Catholic Church said that if you were godparents to the same child you were technically related and therefore could not marry. The two others are executed because they removed the bacon in which some chicken had been cooked: this is thought to reveal their fidelity to the Jewish faith. Though Voltaire believed in God, he thought that established religion served to divide and not to unite people. This scene, depicting the public burning of people who simply failed to conform to what seem to be arbitrary and even insignificant ‘rules’, allows him both to condemn superstitious attitudes to natural catastrophes, and to imply that the world would be better off if reason—rather than blind faith and a slavish adherence to religious doctrine—were to triumph.

So, to recap, there are several reasons why the earthquake matters:

- It is a historical event which would have been familiar to Voltaire’s contemporaries.

- It is a way of showing that natural disasters are not selective in the victims they make.

- It forces Candide to start facing facts: all is not always for the best.

- It demonstrates that optimism is a fallible philosophy.

- It provokes the the auto-da-fé, which shows that religion can be bloodthirsty, and that by encouraging superstitious actions, the Church is clearly pulling the wool over peoples’ eyes.

Candide is known in French as a ‘Conte philosophique’, a philosophical tale. This is because it is a fictional story which is often quite amusing, but one which sets out to teach us something profound and not just to entertain us. Candide’s learning curve is meant to function for the reader too. Like him, we should be asking ourselves what conclusions can be drawn from his different adventures.