This blog post was written by Franklin, a second-year student studying Spanish and Portuguese. Here, Franklin tells us about Eduardo Lalo’s stay in Oxford and the way it shone a spotlight on the Spanish-speaking Caribbean.

Every term, a number of academics from countries in the ‘Global South’ – a term that refers to countries in Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean whose economies are small to medium-sized – arrive in Oxford as TORCH Global South Visiting Fellows. TORCH, short for The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities, collaborates with an Oxford-based academic to sponsor and support the academic whilst they are here hosting events to do with their research interests and current projects.

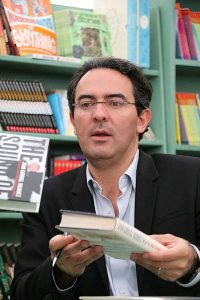

One of the academics Oxford welcomed in ‘Trinity’ term (summer term) was Eduardo Lalo, Professor of Literature at the University of Puerto Rico and a multidisciplinary artist, whose work spans creative writing, drawing and photography. Eduardo’s academic host in Oxford was María del Pilar Blanco, Associate Professor of Spanish American Literature and Tutorial Fellow at Trinity College; together, they devised a range of events throughout the term for him to showcase his work and engage with the local and university communities.

The first of those events was a seminar series entitled ‘The Mis-invention of the Caribbean’. In the three seminars that comprised the series, which brought together students, researchers and members of the wider Oxford community, Eduardo examined the literature of the encounter between the Caribbean and its peoples and Europeans, with key texts including Christopher Columbus’s journal, dating from 1493, and the edition of it annotated by Bartolomé de las Casas, a Spanish cleric whose writings chart the first decades of the colonization of the Caribbean. The series reconsidered the historiography surrounding the ‘discovery’ of the Caribbean, revealing that, at the heart of Columbus’ journal, lie a number of problematics and points of contention, and that, as a text, it cannot always be taken at face value. Beyond Columbus, Eduardo explored works by English travellers in the nineteenth century – texts by such figures as James A. Froude and Spenser St. John – and how they relate in style and content to Columbus’s fifteenth-century diary. In particular, Eduardo analyzed the recurrence of the cannibal as a figure that European writers return to again and again to represent their cultural others.

Alongside his three-part seminar series, Eduardo led a separate creative writing workshop for a group of ten students. After a short question-and-answer session, Eduardo, through a range of exercises, invited seminar-goers to consider the importance of the notion of writing in space (the space of a page of a book, for instance). Those in attendance enjoyed the opportunity to think creatively about, and move through, approaches to creative writing.

Aside from his more academic seminars and creative writing workshop, members of the Oxford community were able to attend an exhibition of his photography, entitled ‘Deudos’, or ‘Death Debts’, held at St John’s College. Eduardo’s black-and-white images of life in Puerto Rico, taken between 2012 and 2018, bring to the fore in powerful detail the realities of day-to-day life in what has been termed the world’s ‘oldest colony’ (Puerto Rico remains a commonwealth of the United States). Held over the course of the fourth week of term, the exhibition was well attended and its venue appropriate, in the light of the recent announcement by St John’s College’s that it will launch a new research project, named ‘St John’s and the Colonial Past’, to examine the role the college played in creating and maintaining Britain’s overseas empire. Eduardo’s exhibition seemed apt at a time when the Oxford community is opening discussions about decolonial approaches to art and scholarly work.

Eduardo’s term as a TORCH Global South Visiting Fellow, then, shone a spotlight on the relative lack of research that is done in Oxford on the Spanish-speaking Caribbean, compared with that done on Spain and South America. His seminar series was a very useful follow-up to Professor Blanco’s lectures in ‘Hilary’ term (spring term) on ‘Literature of the Spanish Caribbean’, providing attendees with important historical context as far as the literary history of the Caribbean is concerned. Equally, it was enjoyable and insightful to explore new approaches to creative writing and to engage with photography, two aspects of the arts under-represented and under-explored in Oxford curricula: approaches that challenge us to think of long-established canons from a decolonial perspective.