posted by Jessica Allen

Digital Humanities are certainly a very modern invention. They are a way of creating a copy or a version of a text, literary or otherwise, and putting this online so that it is available to a wider audience than it would be if only the physical, printed format were available. Whilst looking at a screen is no substitute for having the actual material object in front of you, it’s certainly good to be able to continue reading or researching whilst you are away from university, or to look at rare books without having to journey deep into some stacks. Browsing is also very easy and often free so readers tend to discover a few unexpected treasures along the way.

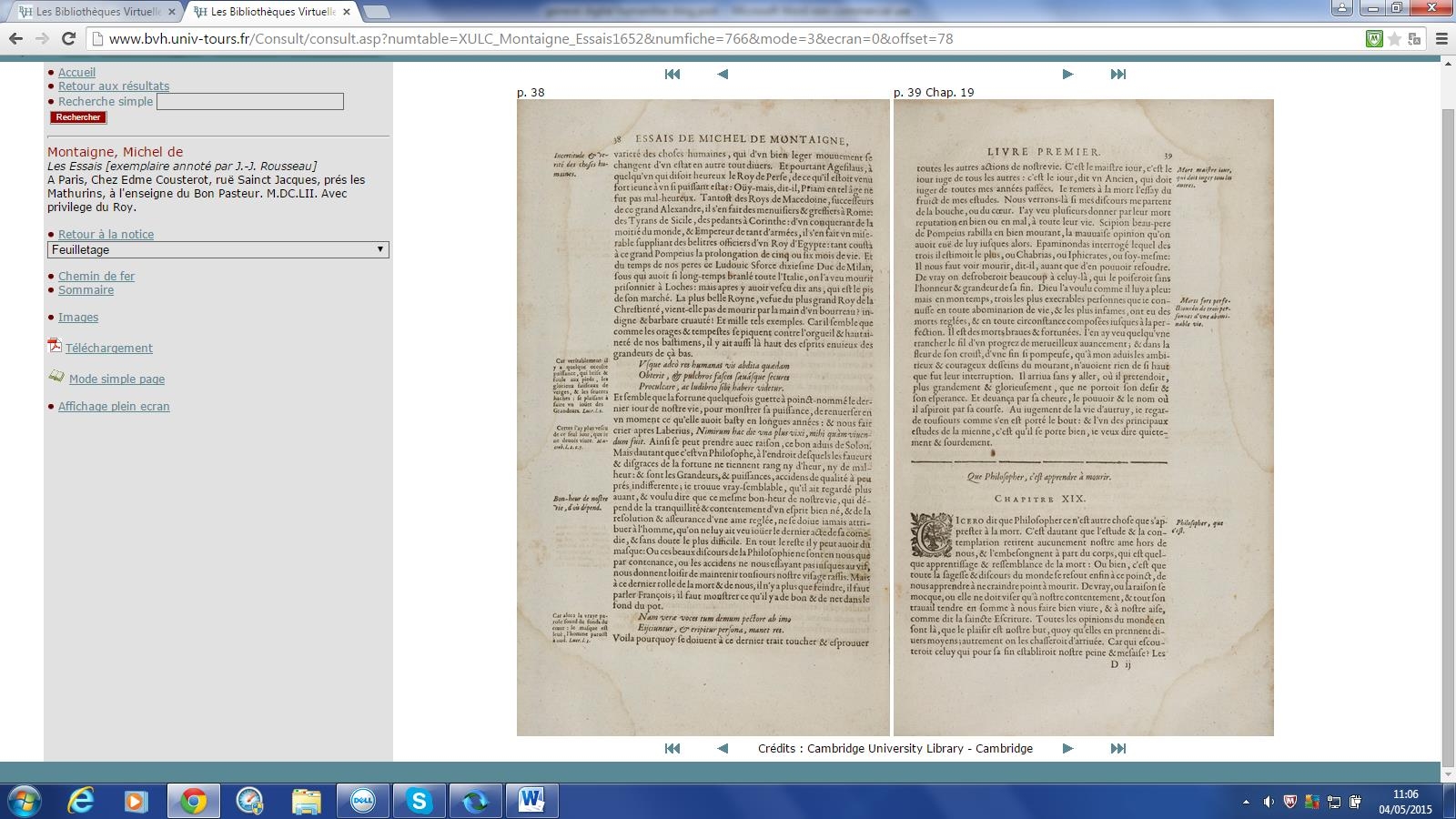

The web is home to an ever increasing number of Digital Humanities projects, so it can sometimes be difficult to know where to start. As part of my year abroad I was lucky enough to intern on a Digital Humanities project in Tours, France. The Bibliothèques Virtuelles Humanistes, often known simply as the BVH, is dedicated to 16th Century French literature and provides Renaissance fans with a treasure trove of manuscripts and first edition printed books in pdf format, as well as searchable transcripts and image databases. The online database is divided into several sections, so I’m going to write about my favourite bits here:

MONLOE (MONntaigne à L’Œuvre)

Michel de Montaigne was a 16th Century French thinker whose three volumes of essais provide the basis for what we consider to be an essay today. In writing his essais, one of his main aims was to offer a portrait of a self which was constantly changing and developing. The online editions are particularly magical because the pdfs allow us to see his marginalia and additions (or his allongeails, as he called them) in their original state, so therefore the development of this self, as well as those added by his editor and fille d’alliance (adopted daughter) Marie de Gournay. The MONLOE corpus also contains books owned by Montaigne himself and sources which inspired the Essais, so it is a must for any Montaigne fan. You can access this part of the library here: http://www.bvh.univ-tours.fr/Montaigne.asp

ReNOM Renaissance

This project focuses on the work of Renaissance writer François Rabelais, most famous for the ground-breaking collection La Vie de Gargantua et de Pantagruel, and of the poet Ronsard, the most prominent member of the Pléiade. Both writers’ texts are peppered with place names, so ReNOM provides surfers with an interactive map which allows them to browse extracts from the books whilst matching them to their real location. This is a brilliant way to make the most of a sightseeing trip and to really make literature come alive. Looking at the map shows just how geographically wide-ranging these texts are: http://renom.univ-tours.fr/fr/cartographie

There’s no better way to discover the Renaissance than by looking at authentic materials, so definitely check out the BVH. Don’t forget that there are online resources to suit all tastes, so if the Renaissance isn’t your cup of tea, perhaps try looking at Gallica (http://gallica.bnf.fr/), which is run by the National Library of France in Paris and covers all periods of literature. Your next literary adventures are just a few clicks away…