posted by Jennifer Rushworth

Many people will have heard of Proust’s ‘madeleine’ moment, where a piece of cake dipped in tea has the power to revive full technicolour memories of the narrator’s past.

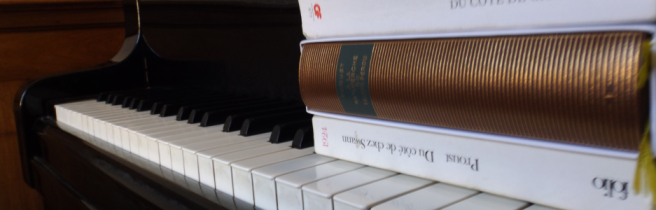

Fewer people will have delved further into Proust’s long novel A la recherche du temps perdu (translated originally as Remembrance of Things Past and more recently as In Search of Lost Time). Even first-year French students at Oxford only read the first two hundred pages of the first volume, Du côté de chez Swann (Swann’s Way/The Way by Swann’s). And there are seven volumes in total to get through (not unlike that more modern classic, Harry Potter…)!

Do read on, however, and you will encounter one of my favourite characters and some of my favourite passages. Meet Vinteuil, a composer. Vinteuil is a strange composer, however, for he is purely fictional or imaginary.

Early readers of Proust’s novel were obsessed with identifying the man behind the mask, and suggested a number of famous French composers whose music you may have heard or played: Saint-Saëns, Debussy, Ravel, Fauré, Franck… In contrast, more recently readers have quite rightly tended instead to read Vinteuil as pointing not to any real composer, but rather as a specifically literary, entirely imaginary manifestation.

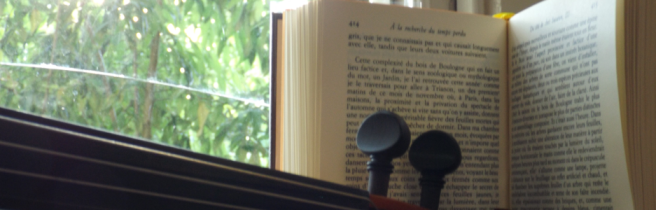

What does it mean for a composer to be fictional or imaginary? It means that their music is essentially silent, heard only in language, and often mediated by the written responses of different characters within the novel.

From Proust’s novel we have only sparse details about Vinteuil’s life. He was a village organist and piano teacher, widowed, and with a daughter. His music earned him neither fame nor riches during his lifetime. Yet two of Vinteuil’s compositions emerge in the novel as sublime works of genius: a sonata for piano and violin, and a septet (a piece for seven instruments, which are never entirely coherently listed by Proust).

Generously supported by the John Fell OUP Research Fund, I am leading a project this academic year (2016–17) to bring to life Vinteuil’s violin sonata.

How can Proust’s novel act as a catalyst for new pieces of music? And what will these new compositions tell us about how musicians read and respond to Proust’s literary music?

Two undergraduate students in Music at Worcester College, Oxford have been commissioned each to write a violin sonata responding to the passages from Proust’s novel where Vinteuil’s sonata is heard and described. These passages have been wonderfully translated into English by a team of undergraduates in French at Oxford, led by Madeleine Chalmers (Cambridge), and can be consulted here in both French and English.

If you can, do join us for a free final concert on Friday 5 May 2017 at the Holywell Music Room, Oxford, to hear these new commissions, alongside readings from Proust’s novel. Free tickets can be booked here.

Alternatively, the new music will be also be available and recorded online, so do check back in May to hear the music of Vinteuil newly imagined by two student composers.

For more information and to explore this project further, please consult the website: https://proustandmusic.wordpress.com/