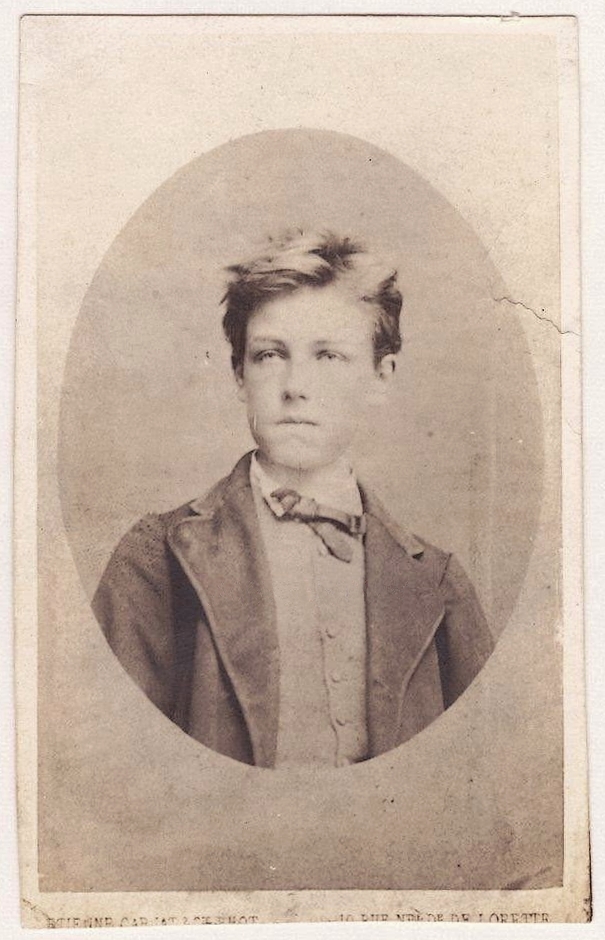

This week’s post explores one of the most famous French poets of the nineteenth century, Arthur Rimbaud, whose collections include Une Saison en enfer and Illuminations. Rimbaud captured the imagination of his readers, both on account of his experimental writing style and his turbulent personal life. Prof. Seth Whidden, Fellow and Tutor in French at The Queen’s College, has recently published a biography on Rimbaud. Here, he reflects on the writing process and the tricky relationship between life and literature.

Writing about one of France’s most famous authors was a daunting task, but what made it less so was what makes his story so compelling to all lovers of literature: year after year, generation after generation. If Arthur Rimbaud (1854-1891) is French teenagers’ perennial favourite, it’s because during the course of his short life and even shorter literary career — he stopped writing poetry by the age of 21 and died at the age of 37 — he embodied some of the fundamental urges that we all have known, at one time or another: bursts of creativity; seeing how far rules can be bent before they break; and the desire to pick up and move away, expanding horizons and learning about self and the world.

Mixing life and literature can be dangerous business: reducing a poem to a biographical detail flattens the poem and removes so much of what makes literature sing (how it sounds, how it’s rhythmed, how it feels, how it moves the reader…). Instead, I set out to weave two parallel stories. Yes, of course, it is helpful to know that ‘Le Dormeur du val’ is dated October 1870, and so Rimbaud set out to his presentation of war’s bloody interruption ruining the bucolic Ardennais countryside just weeks after France capitulated in Sedan, a dozen miles from his hometown. But that knowledge doesn’t tell the full story of the poem, far from it: it leaves out how the final line is prefigured (spoiler alert!) in the repeated vowel sound of ‘bouche ouverte’ of line 5; of how the standard twelve-syllable line is destabilized several times, with punctuation an accessory to the crime:

C’est un trou de verdure où chante une rivière

Accrochant follement aux herbes des haillons

D’argent; où le soleil, de la montagne fière,

Luit: c’est un petit val qui mousse de rayons.

Un soldat jeune, bouche ouverte, tête nue,

Et la nuque baignant dans le frais cresson bleu,

Dort; il est étendu dans l’herbe, sous la nue,

Pâle dans son lit vert où la lumière pleut.

Les pieds dans les glaïeuls, il dort. Souriant comme

Sourirait un enfant malade, il fait un somme:

Nature, berce-le chaudement: il a froid.

Les parfums ne font pas frissonner sa narine;

Il dort dans le soleil, la main sur sa poitrine

Tranquille. Il a deux trous rouges au côté droit.

It is a green hollow where a river sings / Madly catching on the grasses / Silver rags; where the sun atop the proud mountain / Shines: it is a small valley which bubbles over with rays. // A young soldier, his mouth open, his head bare, / And the nape of his neck bathing in the cool blue watercress, / Sleeps; he is stretched out on the grass, under clouds, / Pale on his green bed where the light rains down. // His feet in the gladiolas, he sleeps. Smiling as / A sick child would smile, he is taking a nap: / Nature, cradle him warmly: he is cold. // Odours to not make his nostrils quiver; / He sleeps in the sun, his hand on his breast, / Silent. He has two red holes in his right side. (translation from Rimbaud, Complete Works, trans. Wallace Fowlie, revised Seth Whidden, Univ of Chicago Press)

Life-writing can help connect some dots, though, and such connections are what makes this biography slightly different from others. In order to appreciate what made Rimbaud’s poetry so revolutionary, it’s important to understand the norm from which he made such a clear departure. Readers of this book will learn some of the basic rules of French prosody: just enough to be able to feel some of his creativity and rule-breaking. They will also see that his creativity doesn’t stop when he leaves Europe; instead, I propose a new way of looking at his African period. Rather than repeating the formula that has served the Rimbaud myth well for over a hundred years — Europe means poetry; Africa means commerce — I propose a new narrative in which inquisitiveness and creativity are constants in his life, informing his activities in both periods of his adult life. It can be easy to keep poetry elevated on its pedestal and assume that a life after poetry is an uninteresting one — easy for literary critics who love poetry, anyway! — but if poetry is just one manifestation of a broader creative force, then there can be other possible moments of creativity. They might not measure up to the brilliance of his poems, but their presence in the story of his life might be worthy of a little more attention.

Ultimately, it’s up to the reader to decide: the reader of Rimbaud’s poetry, first; then the reader of this biography. My final chapter poses a series of questions, and I hope that anyone interested in creativity, rule-bending, and seeing the world will recognize therein some of the questions that we all ask from time to time: about literature, about life, about ourselves and about the world around us.