Arthur Wotton, who is currently studying for an MSt in Spanish at The Queen’s College, is writing a dissertation on the Latin American dictator novel. In this post he shares some insights into this enthralling literary genre.

Latin American literature is among the most popular and rewarding options offered as part of a Spanish degree at Oxford. Students have the opportunity to study a diverse and fascinating corpus of literature, and to explore the innovative styles of writing that authors developed in order to respond to the social, cultural and political landscapes of Latin America. Household names such as García Márquez, Borges and Neruda feature on the reading list, as do huge range of literary movements from the 1800s to the present.

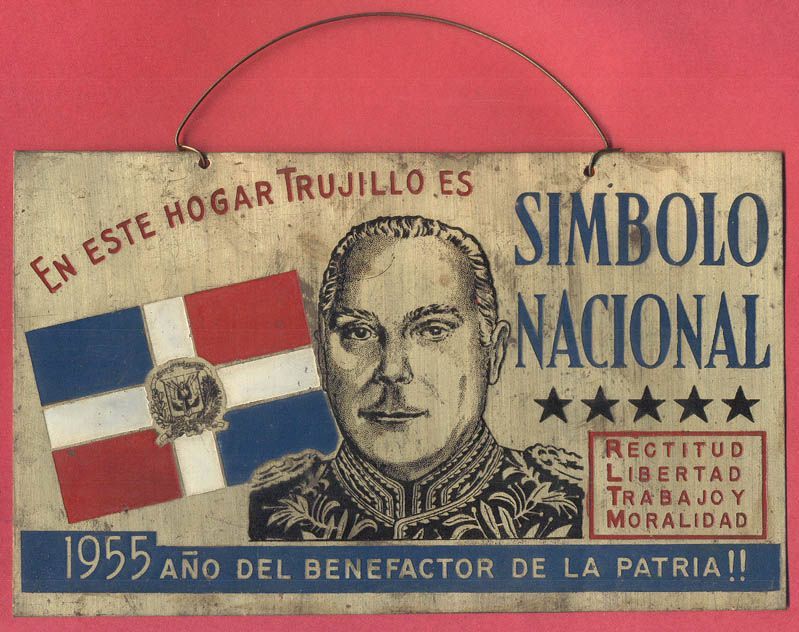

One of Latin America’s most interesting and influential literary traditions reflects a political reality that has been ever-present since independence: dictatorship. A long lineage of caudillos, or strongmen, have loomed large in Latin American politics for centuries: repressive and often brutal figures such as Augusto Pinochet in Chile, Alfredo Stroessner in Paraguay, the Somoza dynasty in Nicaragua, and Rafael Trujillo in the Dominican Republic, who ordered that churches display signs reading ‘Dios en cielo, Trujillo en tierra’ (‘God in heaven, Trujillo on Earth’)!

The dictator novel, or novela del dictador, emerged as a result of writers seeking to challenge, satirise, or come to terms with the impact of dictatorship through representing it in fiction, and the genre came to be one of the most influential and important in all of Latin American literature, involving many of its most famous names. Not only do they focus on political machinations and repression, but in depicting visions of authoritarian societies they tackle a huge variety of themes, including historical memory, appearance and reality, the importance of language, and gender roles.

Here’s a brief look at some key dictator novels:

Miguel Ángel Asturias’s El Señor Presidente (completed 1933, published 1946) is a disturbing and experimental novel, loosely based on the Estrada Cabrera regime in Guatemala. Asturias presents a terrifying society governed by whispers and rumours, where dictatorship permeates all aspects of life: he talks of how ‘una red de hilos invisibles, más invisibles que los hilos de telégrafo, comunicaba cada hoja con el Señor Presidente, atento a lo que pasaba en las vísceras más secretas de los ciudadanos’ (‘a web of invisible threads, more invisible than telegraph wires, connected every single leaf with the President, who was aware of what was going on in the citizens’ innermost entrails’). Everyone, from the raving despot to the capital’s homeless, is caught up in this web of oppression, which is juxtaposed with mundane daily life: prisoners are interrogated while jubilant street parties take place outside, and citizens go about their morning chores as the daughter of an exiled colonel frantically searches for her family.

While Asturias’s dictator is only seen briefly, Gabriel García Márquez delves into the mind of the ruler of an unidentified Caribbean country in El otoño del patriarca (1975). García Márquez uses lots of magical realist descriptions in this novel, which seems to go in circles as the dictator’s ‘dead body’ is repeatedly found in the crumbling ruins of his palace. This gives the book a rather timeless quality, and its rambling sentences, which occasionally take up whole pages, make us think about language and who controls it – just like in Augusto Roa Bastos’s monumental Yo el Supremo (1974), an extravagant and complicated work made up of an interlocking series of conversations and footnotes in which language and writing are central.

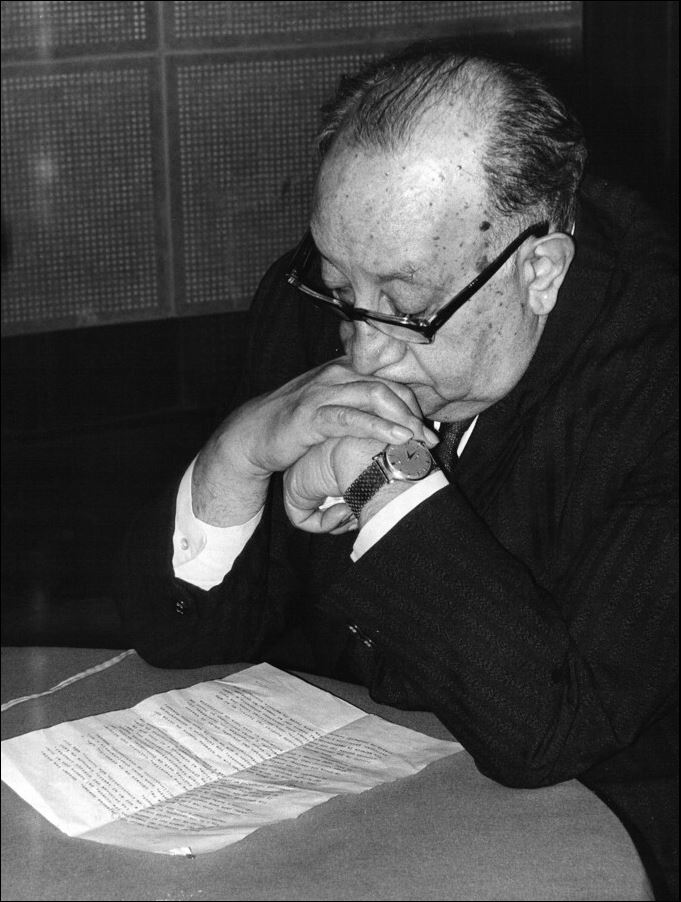

Memory, history and how we approach them are also prevalent themes in the novel of dictatorship. The question of how people can come to terms with the past after the fall of dictators is explored by Mario Vargas Llosa in Conversación en la Catedral (1969) and La fiesta del Chivo (2000 – a staple of the Oxford first-year reading list). These ground-breaking novels alternate between present-day events and characters’ recollections as their protagonists confront the past. In Conversación en la Catedral, Santiago has a lengthy and revelatory conversation with an old acquaintance in a seedy bar in Lima, while La fiesta del Chivo interweaves Urania’s return to the Dominican Republic with storylines explaining Trujillo’s assassination. Vargas Llosa not only presents a comprehensive picture of societies under dictatorship, but also uses large casts of characters to show how different opinions on these regimes come into being.

At turns comedic, unsettling and mesmerising, dictator novels combine vibrant storytelling with a huge range of interesting themes that are bound up in their depiction of autocracies. Hard-hitting and satirical, they are extremely thought-provoking, and it’s fascinating to consider the resonance they still have today. The relationship between executive power and the media has come into sharp focus recently, as have generational political divides like those we see opening up in Vargas Llosa’s novels as family members hold starkly different perceptions of events that took place.

How might El Señor Presidente’s regime operate in an age of social media, when we share so much about ourselves online? And how would we react upon finding out that one of our world leaders had suddenly been transfigured into an enormous parrot made out of words – or tweets? – like Jorge Zalamea’s Gran Burundún-Burundá?

The dictator novel is a rich and powerful genre of Latin American fiction, and is a great starting point for anyone interested in getting into Spanish-language literature. Some of the longer texts described above can be somewhat daunting, so here are some more accessible recommendations:

- Tirano Banderas by Valle-Inclán: perhaps the first true dictator novel, Spanish writer Ramón del Valle-Inclán depicts the ways in which a menacing ruler attempts to crush a revolt and maintain his grip on power.

- El gran Burundún-Burundá ha muerto by Jorge Zalamea: a highly underrated but fascinating ‘poem in prose’ about the funeral of a dictator who had banned the use of language itself!

- Conversación al sur by Marta Traba: two women reunite after many years and reminisce about their time standing against the Argentinian dictatorship as part of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo movement.

by Arthur Wotton

Image credits Wikimedia Commons