posted by Jessica Allen

When looking for an internship for your Year Abroad, definitely think outside the box and never be afraid to approach a company or organisation you might like to work for on the off chance they might be able to take you. As my time at Montaigne’s Château drew to a close last summer, my thoughts turned to the two month long Easter Vacation I would have from my German university. I knew I wanted to spend this in France but at that point, I was starting to doubt whether anywhere would take me for that amount of time.

However my fears were left unfounded and I quickly managed to secure the internship of my dreams. I mentioned to my boss at the château that I needed to find another placement and she knew that I’d spend much of my free time whilst I was there enjoying the books about Montaigne. One of my favourites focuses on the famous beams in Montaigne’s library, known for their Latin and Greek inscriptions. My boss then suggested that I contact Alain Legros, a frequent visitor to the château and the author of the book. So I quickly translated my CV into French and wrote a letter outlining my interests in 16th Century French literature, my future career plans, and my need for an internship. Within two days I had a reply. He couldn’t offer me anything himself, but he is an associate researcher at the CESR (Centre d’Etudes Supérieures de la Renaissance – the Centre for Renaissance Studies) attached to the University of Tours, so he passed my CV onto someone who could: Marie-Luce Demonet, a Professor of Renaissance French Literature and director of the BVH, the project on which I worked. Within three days, I had a positive response and everything was confirmed after a brief meeting in Oxford in September to discuss practicalities: I had a seven week internship in Digital Humanities in Tours!

But before I could get too excited, I had to find somewhere to stay. Finding accommodation in France can be tricky at the best of times due to the huge amount of bureaucracy, and for a two month stay, I didn’t fancy that. Admittedly I started panicking when the university accommodation website was incredibly unhelpful and looked at Tripadvisor on a whim. I managed to find a studio in the centre of Tours, a ten minute walk from where I would be working and which cost only a fraction more than the university accommodation. I could hardly believe my luck and spent eight wonderful weeks living an almost surreal grown-up existence in the city centre.

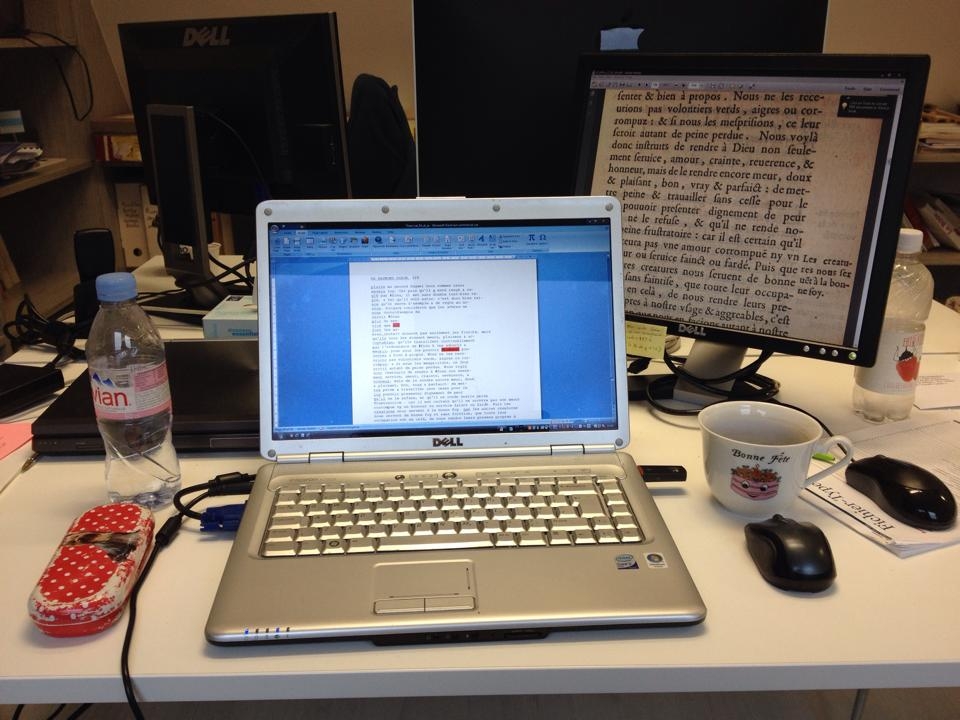

My daily life in Tours was similarly exciting. As an undergraduate who hopes to have a career in academia, I got the chance to experience life at a research centre. I worked on the Digital Humanities project MONLOE < http://www.bvh.univ-tours.fr/Montaigne.asp> (MONtaigne à L’Œuvre), which aims to publish digital versions of the sixteenth century philosopher’s essays as well as the books which were once in his library or the sources of his essays. I spent most of my time learning how to edit transcripts and use TEI-XML coding, two transferable skills which were completely new for me, so it was a very intense and beneficial experience. I was trusted to work on a real project, the digitisation of this book, http://www.bvh.univ-tours.fr/Consult/index.asp?numfiche=1136&url=/resrecherche.asp?ordre=titre-motclef=theologie%20naturelle-bvh=BVH-epistemon=Epistemon, which, after further editing and several control checks by other members of the team, will eventually appear online as part of the virtual library. It was very rewarding knowing that what I was doing was actually useful and part of a real project, something which can be rare in the world of internships. I also had the opportunity to go to conferences held at the CESR, looks at rare books in the reserve, use the extensive library, and meet professors working on the things which interest me. The other members of the team were friendly, welcoming, and easy to talk to – it’s always good to work in an environment where there are others who share your interests.

I worked five days a week from nine until six with an hour for lunch. On Fridays, we would go out for lunch as a team, but on the other days I would go and read by the Loire, try out the cafés around the centre, or browse the nearby shops: you can achieve a surprising amount in an hour. Staring at a computer screen all day and doing everything in French was quite tiring, so after work I often just spent the evening relaxing. When I had more energy, Tours was a great city to be in. The cinema, theatre, ice rink, swimming pool, and other attractions, were all within walking distance and every week the university holds events for people interested in languages, so it was easy to meet new people.

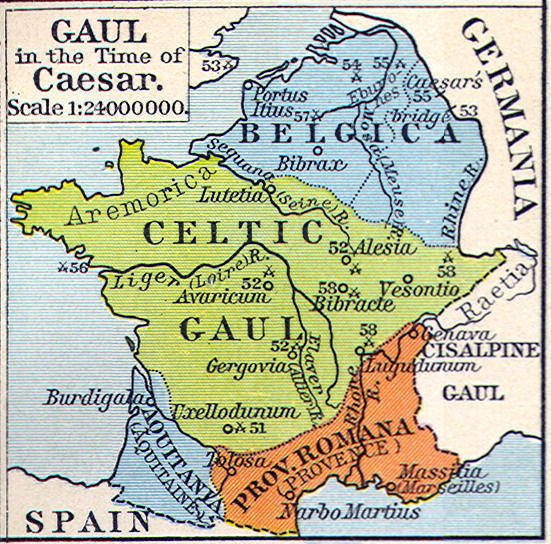

Located in the Centre region and in the Loire Valley, Tours was an ideal place for weekend excursions. With a Carte Jeune (the equivalent of a Young Person’s Railcard), I went to Paris three times, Versailles, Orléans, Angers, and also numerous chateaux all over the region, without ever paying more than fifteen euros for a train ticket. At times it felt like I really was in the Renaissance.

Overall, this internship was thoroughly enjoyable, opened my mind to the possibilities offered by an academic career, and had relatively few disadvantages. Obviously an interest in the literature of the French Renaissance was essential and, having spent so many of my waking hours editing 16th Century French, I now often find myself spelling like a Renaissance person, although this is easily rectified. This kind of internship might not be suitable for someone who would prefer to be with lots of people their own age. I enjoy spending time with people older than me, so being the youngest in the office and the centre itself didn’t phase me, but it might not be for you if this would bother you. If there is somewhere you would really like to work but they don’t seem to offer internships, I would always suggest sending that speculative letter…you never know where that might take you!