These days, most languages that you might want to study at university can be started from scratch. Oxford offers beginners’ courses in all our languages apart from French and Spanish, which means you can pick up any one of the following that takes your interest:

German

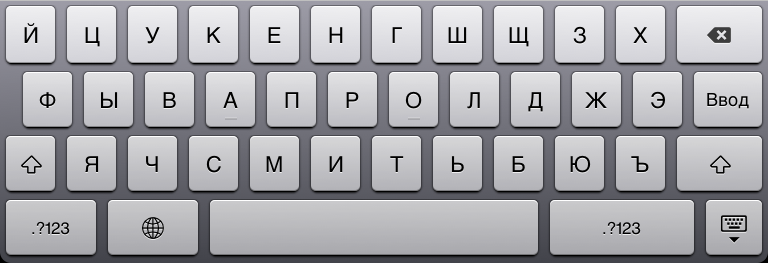

Russian

Italian

Czech

Portuguese

Greek

Polish

Plus, within each of our language courses are options to explore further related languages, including Bulgarian, Croatian, Ukranian, Catalan, Galician, Yiddish, Occitan.

And as well as the Modern Languages Faculty, two other Oxford faculties teach languages, several of which are available to combine with ours in a two-language degree.

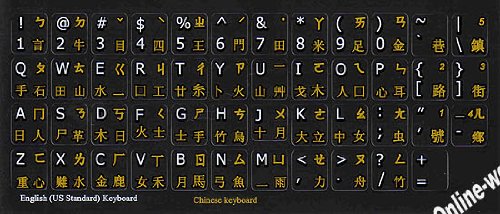

The Oriental Studies Faculty offers Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Sanskrit, Hindi, Urdu, Arabic, Persian, Hebrew or Turkish (last four available in a combined course with modern languages).

And the Classics Faculty offers Latin and Ancient Greek (both available in a combined course with modern languages).

So if you’re at all curious about trying something new, there’s lot’s to choose from.

Around the time that Oxford opened its Beginners’ German course, the Guardian newspaper published a story exploring beginners’ languages in UK universities. Here’s an extract:

Though it’s difficult to detect in admissions statistics, university language courses are changing, with more opportunities for students to study a language from scratch. Ab initio courses, as they are termed, once the preserve of Russian, Chinese and Arabic, are now being extended to include more familiar languages: Spanish, sometimes French and especially German. In some universities, such courses are long established, but others are making new forays: Oxford offered beginners’ German for the first time this year (available in joint honours to students with an A-level in another language); King’s College London, went further and this year offered German from scratch with a range of subjects. Manchester has introduced French from scratch – plus the chance to add a language as a minor degree subject.

For Lauren Valentine, 19, completing the first year of a single honours French degree at Manchester, the university’s new “flexible honours” programme has allowed her to fulfil her dream of learning Spanish, foiled when her school split her year into two random language groups and she ended up with French. “I was always embarrassed on family holidays when all I could say was una cola lite,” she says. “I couldn’t do Spanish at sixth-form college either, and I didn’t have the confidence to apply for joint honours with Spanish ab inito because I thought it wouldn’t ever be as good as my French.

Advertisement

“We did a lot of intensive grammar in the first year, and I feel that my Spanish is now above A-level standard, though the vocab will take more time to bed in. The course has given me even more than I’d hoped, and I now want to go into translation or interpreting.”

The new Manchester programme, introduced this year and allowing students to take a “minor” in a range of subjects including languages, is designed to catch students who might not have considered languages, or perhaps lacked the confidence to apply to study them at degree level. While the university still demands at least one good language A-level for traditional joint honours language courses, the minor courses require no prior language experience. This year, 30 out of 53 students taking a minor chose a language, and the vast majority plan to carry on – with a few even switching to full joint honours.

The scheme allows students to “dip their toe in the subject” for a year without risk, says assistant undergraduate director, Joseph McGonagle, and if they do continue they can get a language on their degree certificate. “The feedback is brilliant – they are grabbing it with both hands.” The hope is to double the numbers this September, he says. “This is about rebuilding from a low base – or a different base. We can’t let the popularity of school languages decline and not address that at university level.”

[…] At Oxford, ab initio German introduced this year has proved popular, and nine students are signed up for September (compared with 70 who have German A-level). Beginner students are taught very intensively and therefore their numbers will, for now, be capped at 16, says Katrin Kohl, professor of German literature.

The new course, Kohl notes, has attracted students drawn to German in diverse ways: perhaps through an interest in the economy, through family connections, or after reading something influential.

Jocelyn Wyburd, chair of the university council of modern languages and director of the language centre at Cambridge, sees the expansion of ab initio as “universities grappling with a pipeline problem” – a “woeful” 48% of the GCSE cohort last year took at least one language.

A strong fight back by language departments, mainly through the Routes into Languages campaign, plus government initiatives, may ultimately see a turnround in language take-up in the UK. But for now, Wyburd says, universities are “reinventing their rules. Each department is devising its own pathways and constantly reviewing what are the non-negotiables.”

Can ab initio rescue languages? “It can. Will it? I don’t know – I’d love it to. But it’s not a panacea.”