While the blog is on its summer holidays, here are a selection of the best posts from the past couple of years. We’ll be back on the first Wednesday in September with another question on an A-level text: ‘Just how clever is Lou from No et Moi?’

posted by Madeleine Chalmers

Montmartre is a legendary part of Paris – a maze of twisting cobbled streets, trees, squares, that leaves you breathless, and not just from the steep climb.

Tucked away discreetly in a side street behind the Sacré-Coeur, the Musée de Montmartre keeps the memory of the area’s heyday in the late 19th and early 20th centuries alive. Set in beautiful gardens overlooking the Montmartre vineyards, the museum’s collections are displayed in the house of artist Suzanne Valadon and her son Maurice Utrillo, a building which played host to the most dynamic and innovative artists, painters, and composers of the day. A zinc-topped bar counter, a battered piano with yellowed keys, photographs, paintings, and sketches all conjure up a time when Montmartre was the centre of an extraordinary creative ferment, and a lodestone for artists from across Europe, who would arrive with no money and no French, confident of a generous Montmartrean welcome, with kindness and credit freely given.

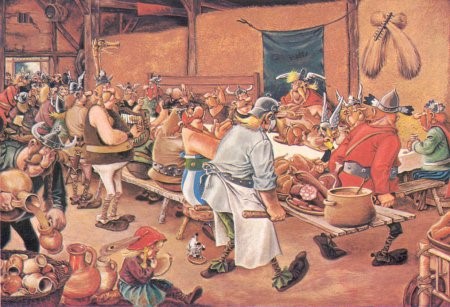

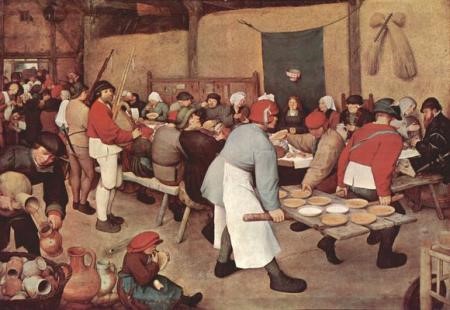

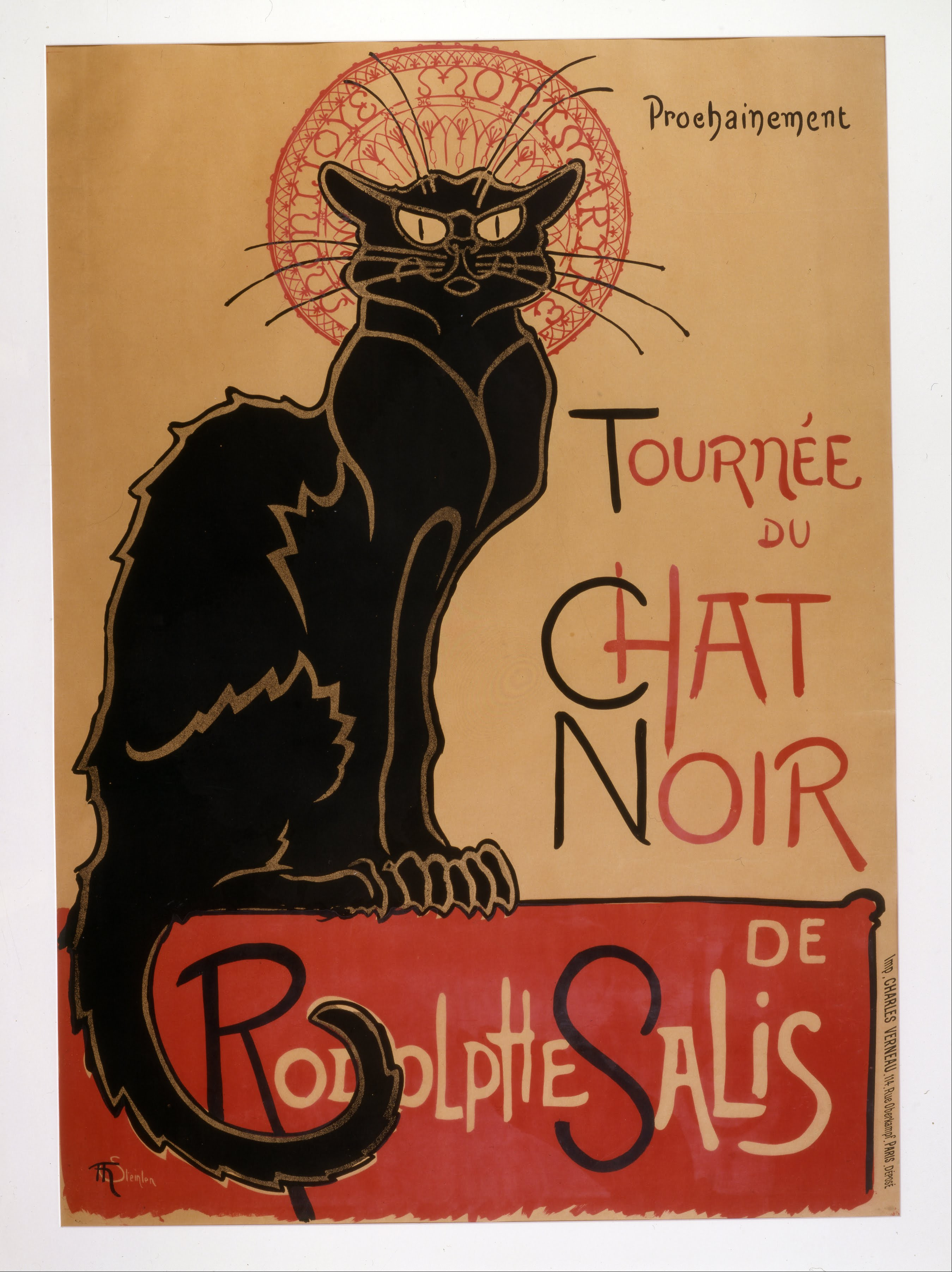

Alongside the Moulin Rouge, two iconic cabarets loom large in the museum’s collections: the Lapin Agile and the Chat Noir. Lithe, mischievous, and living by their wits, the nimble rabbit and black cat which form the Montmartre menagerie perfectly encapsulate the spirit of the area. Opened in 1855, the Lapin Agile still offers a nightly dinner and cabaret show 160 years later, although the atmosphere is somewhat different. In the late 19th century, you would step into a spicy fug of tobacco smoke and sweat, the aniseed burn of absinthe hitting the back of your throat. Ears ringing with the plaintive wheeze and rasp of an accordion, and the sound of bawdy, full-throated laughter, you would take a seat at one of the sticky tables, scored with the initials of your predecessors. You never knew who you’d be rubbing shoulders with: wealthy Parisians slumming it for a night, artists’ models, dancers, political radicals, ladies of the night, local eccentrics of every stripe, penniless poets with inkstained fingers or hungry artists still spattered with paint, come from unheated attics and studios to warm themselves with drink and friendship, and to listen to the chansons réalistes of poets such as Aristide Bruant. As their name suggests, these were songs which told the truth about Paris and the seamy underbelly of its nightlife, in a distinctive slang. They were tales of poverty, prostitution, violence, heartbreak, hopeless love, but also bawdy, innuendo-laden or just downright filthy sing-a-longs. They’re emblematic of gouaille – a uniquely Parisian trait, a blend of bolshy straight-talking, cheek, and bravado, with an underlying hint of vulnerability. It’s tempting to sanitize or romanticize the sordid reality of life in Montmartre, but these songs express the extremes of existence there – all human emotions and situations, from joy to misery, expressed with equal intensity.

Montmartre has retained its strong sense of identity: its inhabitants are still defiant outsiders and unrepentant eccentrics, helping each other out and fighting to preserve their traditions. Looking down from the gardens of the museum and imagining summer evenings heavy with the smell of ripening grapes and raucous with the din of the Lapin Agile, it’s easy to fool yourself into hearing the clack and swoosh of the windmills which used to dot the Montmartre hillside – and feeling the breeze of anarchy.

And if you’re interested…

… here’s a flavour of Montmartre’s cultural output during its heyday.

Art

With their exuberant colours, effervescent energy, and startling shapes, these are definitely worth a look:

Poetry

A larger than life figure, Guillaume Apollinaire was an experimental poet and the father of Surrealism. In his collections Alcools (1913) and Calligrammes (1918), he uses words which are simple individually, but puts them together in surprising combinations. He plays with the layout of his poems on the page to form verbal flowers or fireworks.

A particular favourite of mine is Le Pont Mirabeau (here in the original French, with English translations, and musical French versions).

Music

- ‘Milord’ – In this rambunctious number, Edith Piaf, the ‘Sparrow of Montmartre’, encourages a broken-hearted lover to drink and dance away his sorrows:

- ‘Rose Blanche (Rue St Vincent)’ – an iconic poet from the Lapin Agile, Aristide Bruant here sets his pen to tell of a woman’s tragic end at the hands of her gangster lover, on the Rue St Vincent in Montmartre (here in a rendition by variety star Yves Montand)

Films

- Le Fabuleux destin d’Amélie Poulain (2001)

- A modern take on the area, but which has an unmistakeably quirky Montmartrean charm. The director Jean-Pierre Jeunet lives in Montmartre and is a familiar face in its various restaurants and bars.

The Musée de Montmartre can be found at: 12 rue Cortot, 75018 Paris

Madeleine Chalmers.

I’m a 3rd year French student at St John’s, currently on an Erasmus study exchange at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris. I have been known to give the odd rendition of a chanson réaliste on my accordion.

![‘… a parler, bien sonere et parfaitement escrire douce frances qu’est la plus belle et la plus gracious langage et la plus noble …’ [A detail from a manuscript of the Manière de langage, Cambridge University Library, MS Dd.12.23, f. 67v.]](https://farm4.staticflickr.com/3847/14940771507_dc23047502_o_d.png)

Thanks for these most interesting examples. I agree that Trevien is by far the best of the translators here who try to preserve poetic form, but there are still some terrible word choices: for instance, haunting for mystique is a mistranslation, pure and simple. There’s no good reason for it, either, since the syllabication of the two words is the same.

Which brings me to your point about there being no objective standards by which to judge better and worse translations of poetry. It seems fairly clear that any translation which distorts a poem’s meaning is a worse translation than one which doesn’t. So, my bias, if you want to call it that, is for translations that preserve the meaning, including, insofar as possible, connotations, associations, and nuances, over form.

For me, then, Aggeler is far and away the best translator of Baudelaire sampled here, and I would also disagree that no one could tell from looking at his translation that Baudelaire has written a sonnet. The stanzaic structure and number of lines will strongly suggest the form to any reader who knows the technical requirements of the sonnet in the first place.

I also think that the best way to read foreign-language poetry is in a bilingual edition with the original and the translation on facing pages. Even if one has only “schoolboy French”, one can get a sense of the form, meter, and rhyme scheme from Baudelaire’s poem, and also, via a translation such as Eggeler’s, grasp the meaning.

P.S. Perec omitted the letter “e” (no “Googling” involved).

I have just published my own translation of ‘Les Fleurs du Mal’, available on Amazon in three editions. Here is my version of Les Chats, which I hope compares favourably with the above translations:

When ardent lovers or austere scholars grow old,

Both are disposed to love, in their maturity,

The powerful, gentle cat, pride of the family,

Who like them loves to sit, and like them shuns the cold.

Friends of both science and of sensuality,

Cats like to seek the silent horror of the dark;

As stallions of Erebus they’d have made their mark,

Had they to servitude inclined their dignity.

As they dream, they adopt the noble attitude

Of a great sphinx, recumbent in deep solitude,

Seeming to dream forever in its native land.

From their generous loins mysterious sparks arise,

And particles of gold, like grains of finest sand,

Reflect like stars behind their enigmatic eyes.

I have made one or two amendments to the above translation. I have changed “disposed” to “inclined” and and have made slight alterations to the two tercets, especially the last line which now has a more literal translation.

LVI. – CATS

When ardent lovers and austere scholars grow old,

Both are inclined to love, in their maturity,

The powerful, gentle cat, pride of the family,

Who like them loves to sit and like them shuns the cold.

Friends of both science and of sensuality,

Cats like to seek the silent horror of the dark;

As stallions of Erebus they’d have made their mark,

Had they to servitude inclined their dignity.

As they sleep, they adopt the noble attitude

Of the great sphinx, recumbent in deep solitude,

Seeming to dream forever in its desert land;

From their abundant loins magical sparks arise,

And particles of gold, like grains of finest sand,

Confusedly bestar their enigmatic eyes.