In an occasional series, we’ll be dropping in on our former Modern Languages students to see what they are doing now, and how the skills they’ve learned in their degree course have led them to their chosen career. This week, Daniel Abu, who studied French and Italian for his undergraduate degree at Oxford, talks about how his studies have led to a career in Marketing at a Brand Strategy Consultancy.

Monthly Archives: September 2021

Transferable skills from the Modern Languages Degree: Narrative in Business

One of the challenges facing modern languages today is justifying the subject to students in terms of its employability and transferable skills, particularly in competition with STEM subjects. A new report funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council and carried out by Oxford University will help make that case.

‘Storycraft: the importance of narrative and narrative skills in business’ based on interviews with major UK business leaders, shows the demand for a ‘narrative skillset’ in CEOs, managers and employees of twenty-first century business.

The narrative skillset comprises:

■ Narrative Communication

■ Empathy and Perspective Taking

■ Critical Analysis, Synthesis, and Managing Complex Data

■ Creativity and Imagination

■ Digital Skills

And the study found that Arts and Humanities degrees like Modern Languages are seen by business leaders as specialising in a range of skills that foster this area, such as essay writing, critical thinking, creative thinking, rhetoric and persuasion, storytelling, cross-cultural studies, social analysis, and dealing with ambiguities.

Some of the key findings of the research study are that:

■ Narrative is a fundamental and indispensable set of skills in business in the twenty-first century. The ability to devise, craft, and deliver a successful narrative is not only a pre-requisite for any CEO or senior executive, but is also increasingly becoming necessary for employees in

any organisation.

■ Narrative is about persuading another person to embrace an idea and act on it. Narrative exists in action rather than as a static message.

■ Narrative is necessary for a business to communicate its purpose and values. This reflects dramatic societal and economic changes this century by which society as a whole and employees, especially younger ones, expect businesses to live and operate by positive values.

The old corporate objective of focusing on maximising shareholder financial returns is no longer sufficient.

■ A successful narrative must be authentic and based on facts and truth.

■ Audiences for business narratives are becoming increasingly numerous and diverse. Previously, businesses would focus external communications on core audiences such as customers, suppliers, investors, and regulators. Now businesses must engage with a wider

variety of stakeholders and a diverse workforce, actively taking a position on key social issues including the environment, social well-being and the community.

■ Writing is a critical part of narrative, but it is as much a performative as it is a written form of communication. Body language, facial expressions, staging and engaging an audience are as important as the written word when it comes to disseminating a business narrative.

■ Diversity is integral to narrative on two levels. First, in a multicultural society like the UK even an internal narrative for domestic employees must appeal to people from different cultural, ethnic, gender, linguistic, religious, and educational backgrounds. For businesses with offshore

operations those narratives must cross geographic, social and cultural borders. Second, the devising and crafting of a business narrative must be done by a diverse group of people, reflecting the differences in background among audiences as highlighted above.

■ Arts and Humanities university degrees are better placed than others to train graduates with narrative skills, but narrative should also be taught across STEM (Science, Technology, Education, and Mathematics) disciplines as well and the Arts and Humanities should not be seen as having a monopoly on narrative skills. The consensus among business leaders interviewed for this project is that the education system in England – at secondary and tertiary levels – is too siloed for the needs of the economy in the twenty-first century, forcing students to choose between either the Arts and Humanities or STEM-related subjects too early. Instead, they argue that the education system should encourage and support students to undertake multidisciplinary

courses of study, because business problems require multidisciplinary solutions.

You can read the full report here.

LAND FAR FROM TRANQUILITY:

SPOTLIGHT ON POLISH ROMANTICISM

by ALEKSANDRA MAJAK

Seldom does a literary epoch, philosophical movement, or aesthetic proposition divide readers as much as Romanticism. And no matter what we do or study, when our preferences and affinities with Romanticism are at stake, they tend to be an either/or option. When we think about the end of the eighteenth century, we are likely to recall (in tranquillity or not) the well-known image of a wanderer above the sea of fog from Caspar David Friedrich’s 1818 painting or one of J. M. W. Turner’s atmospheric landscape or marine paintings.

We are quick to talk about it all in bullet points: ‘extreme individualism’, ‘introspection over objectivity’, ‘return of the irrational and fantastical’, ‘poetical genius and inspiration’, ‘escapism’, ‘renewal of oral and folklore tradition’. The list goes on. Nevertheless, characterising the whole literary epoch by extrapolating from several, albeit influential, artworks or reading salient poems does not give a full picture. Ranging from the emotional unrest of the early Sturm und Drang movement in Germany; through the huge impact French Revolution had on all European art, to the metaphysical conundrums of the Russian poet and writer Alexander Pushkin, Romanticism is far from monolithic.

In England, the words that are often invoked to describe romantic principles are these of William Wordsworth from Lyrical Ballads (1798). Poetry, for him, is ‘the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings’ that ‘takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquillity’ [1]. Years later, in his seminal 1919 essay about the representation of feelings in modern verse, modernist poet T. S. Eliot would attack a long-dead Wordsworth by opposing an idealistic romanticism of tranquillity and modern unrest [2]. The Wordsworthian idea from The Prelude was indeed romantic. And here, we may use ‘romantic’ in its adjectival and colloquial sense that indicates — to follow OED — a certain quixotism, sentimentality, naivety, or idealism.

If Wordsworth saw the historical moment as ‘a glorious time’ full of the ‘events / Of that great change’, others had reasons to be less optimistic. The roots and ambitions of Romanticism differ from country to country. By this logic, only by exploring paths ‘less travelled by’ – to follow Robert Frost’s ironically mainstream line – can we widen our understanding of the period and maybe even challenge the myths surrounding ‘unified’ Romantic sensibility and so-called ‘organic form’?

The glory of honourable defeats

Romanticism might well be glorious in the grandiosity of its poetic aspirations but – in Polish literature – it was far from tranquil. After the subsequent partitions (1772, 1793, 1795) of Poland between neighbouring Russia, Austria, and Prussia the country was totally swindled and spend 123 years under occupation. So, formally, there was no country, and Poland was erased from the maps of Europe. The suggestively entitled painting Rejtan, or the Fall of Poland by acclaimed artist Jan Matejko depicts Partition Sejm in 1773 and Rejtan’s (the character on the right bottom corner) dramatic protest against it.

When twenty-year-old Matejko finished Rejtan in 1866, the painting gave rise to heated debate. With the still-fresh memory of the failed January Uprising (1863) hanging heavily in the air, the young painter decided to criticise the elites and their responsibility for Poland’s tragic political situation. Cyprian Kamil Norwid — a late-romantic poet — would, for instance, criticise the painting, saying that ‘Rejtan is a demon with a moustache’. The daunting situation had a lasting impact on the culture and even the current national anthem, composed in 1797, opens with the line: ‘Poland has not yet perished / So long as we still live’. Given the genre, ‘not the most optimistic or conventional opening’ — as one of my undergraduate students aptly observed.

One of the many problems with Polish romanticism is its self-perceived seriousness, its idealised self-image, its lack of critical detachment. All of these continue to impact today’s perception of national symbols that are too often prone to political manipulations. The prominent critic and scholar Maria Janion thought about these issues diagnosing, after 1989, the end of the Romantic paradigm. Still, if transformation brought Poland a free market, rapid economic development, and international mobility; ‘how would Poles define themselves when they had nothing to fight bravely against?’ [3]

Even if Polish writers shared and borrowed from all European traditions, the role ascribed to literature differed from its Western counterparts [4]. The poet was treated like a prophet, soothsayer or bard while poetry was read seriously and in the hope that it would have some causative power. It is common to refer to the well-known trio of Polish romantic poets – Adam Mickiewicz, Juliusz Słowacki, and Zygmunt Krasiński – as wieszcze narodowi, meaning ‘The Three Bards’.

Literature fights against oppression

Still, the oddest idea developed by Polish romanticism was ‘Poland as a Christ of Nations’ that made Roman Catholic Christianity a distinctive part of its cultural heritage. The canonical literary works of the time drew a parallel between Poland’s suffering and the suffering of Christ. This messianism was therefore used by Poles in their fight for eventually re-gaining independence in 1918.

In his late and unfinished poetic drama Forefather’s Eve, Mickiewicz would fortify this tradition. His hero, Gustav, is a typically self-absorbed romantic lover. Here, however, Gustav transforms into Konrad, who is determined to fight against oppression. Notice how the symbolic death and rebirth of the hero is represented graphically, as if alluding to the ancient genre of epitaph so the text that is inscribed on a tombstone or plaque.

Ironically, the title of Mickiewicz’s drama, Dziady, which established the idea of ‘Poland as a Christ of Nations’ comes from nothing other than… a Slavic pagan ritual! The ritual of dziady was a feast of commemoration of the dead now celebrated mostly, if not only, in Belarus. It also made it into the game based on Andrzej Sapkowski’s saga, The Witcher 3 where one of the quests is to meet the master of the ceremony and help villagers in addressing incoming souls.

Well-educated, well-read, having lived abroad, and determined to address ‘Young Friends’ who are ‘Strong in unison, reasoned in rage’, the great rivals Mickiewicz and Słowacki began their work with youthful enthusiasm. They set their youthful energy and rebellion against the inertia of their elders. Sometimes, like in my favourite romantic poem My Testament by Słowacki, both patriotism and youthful determination intertwined. Think, for instance, about the following passage. Now, you may even recognise Slowacki’s allusion to the forefather’s eve ritual.

But you that knew me well, in your reports convey

That all my younger years were for my country spent:

While battle raged, at mast I stood, be as it may,

And with the ship I drowned when vanquished down she went.

Oh that my friends at night together gathered be,

And this sad heart of mine in leaves of aloe burn!

And give it then to her who’s given it to me.

Thus mothers are repaid: with ashes in the urn.

Oh that my friends around a goblet sit once more,

And drink unto my funeral and their poor lot.

Be I a ghost, I will appear and join them or —

If God may spare me pain and torture — I shall not.

But I beseech you — there is hope while there is breath.

Do lead the nation with a wisdom’s torch held high,

And one by one, if needed be, go straight to death,

As God-hurled stones that densely over ramparts fly. [5]

The last stanza of the excerpt exemplifies how Slowacki urges his friends to sacrifice their lives in the fight for freedom. Moreover, years later, in 1943, Aleksander Kaminski would use Slowacki’s words for the title of his book Stones for the Rampart. Through the book we, yet again, see how authors echo the romantic vision of sacrifice as the story follows a group of young friends whose hopes, dreams, and joys of their early twenties are interrupted by the outbreak of the Second World War and the failure of the Warsaw Uprising. In his war movie Warsaw 1944 (available on Netflix) Polish director Jan Komasa borrows from romantic imagery, ideals, and myths. The English trailer gives a sense of this post-romantic symbolism.

The urgency of longing

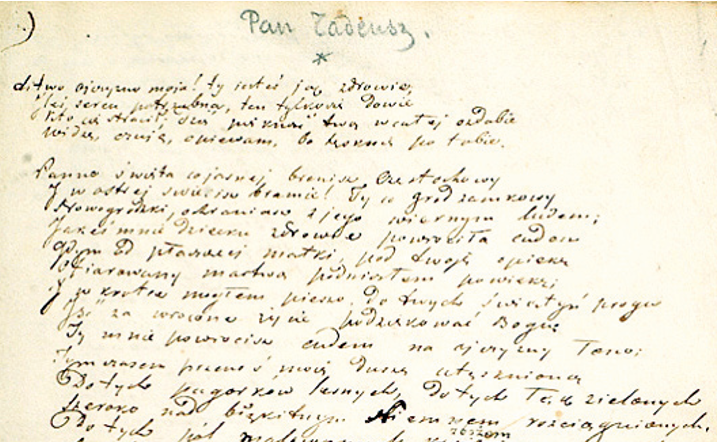

Sometimes poets would evoke political messages less directly, for instance, by adopting a nostalgic tone. One of the most well-known lines of Polish Romanticism comes from the epic poem Pan Tadeusz, written by Mickiewicz and published in Paris in 1834. The most recent English translation of the book – by the acclaimed translator and former Oxford student, Bill Johnson – is brilliant and gives the poem the freshness and dynamism that canonical works every so often lack if read within their own cultural circle. [6]

The epic, like all epics, begins in a serious, high-style tone that does justice to the author’s yearning for the missed Fatherland:

Lithuania! My homeland! You are health alone.

Your worth can only ever be known by one

Who’s lost you. Today I see and tell anew

Your lovely beauty, as I long for you.

The epic has the subtitle ‘The Last Foray in Lithuania’. Across twelve books, all written in the unique metre of the Polish alexandrine, Mickiewicz tells the feel-good, nostalgic story of the eponymous Sir Tadeusz. He is a young man from an upper class of nobility who returns from his studies abroad to an idyllic Soplicowo. In a way, the character of young Tadeusz enables Mickiewicz, as an author, to express his personal longing.

[…] Meanwhile, transport my yearning soul

Back to those wooded hills, those meadows wide

And green, that line the pale blue Niemen’s side;

Those fields adorned with many-colored grain

Where golden wheat and silvery rye both shine,

Where clover with its maidenly red blush,

White duck wheat, and amber rapeseed all grow lush,

Ribboned round by a green field boundary where

A tranquil pear tree nestles here and there.

Even if the scenery is indeed tranquil, the reader knows the backstory that makes such an idyllic description of nature into something more complex, and ambivalent, filled with juxtapositions that are not obvious at the first glance.

Full of national traditions, subtleties, and idiosyncrasies, much of Polish romantic poetry, epic, and drama was written against the grain of failed uprisings, buried hopes, tragic defeats, and longing for a lost fatherland as expressed by émigré writers. The well-known historian of Eastern Europe, Norman Davies, observed that the Polish political microclimate allowed ‘myths to flourish’. And since myths are known to have broad applications and functions, it is now fascinating yet dramatic to observe how the romantic ideas strongly embedded within Polish culture have or have not been used.

[1] More about the leading ideas and forms of European Romanticism can be found in a comprehensive book by Nicholas Roe, Romanticism: An Oxford Guide. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

[2] See https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/69400/tradition-and-the-individual-talent

[3] See the article by Stanley Bill in Being Poland : A New History of Polish Literature and Culture since 1918 ed. Czaplinski, P., Nizynska, J., Polakowska, A., & Trojanowska, T. (2019). Toronto, 2019.

[4] More about the political underpinnings of Polish Romanticism see: https://culture.pl/en/article/polands-unique-take-on-romanticism-why-is-it-so-different

[5] http://wolnelektury.pl/katalog/lektura/slowacki-my-testament

[6] See https://archipelagobooks.org/book/pan-tadeusz-last-foray-lithuania/

FRENCH FLASH FICTION: THE FINAL STORIES

And here are the last brilliant stories from the Year 12 and 13 highly commended entries in the French Flash Fiction competition 2021:

Sur une île isolée, il ne restait plus que deux hommes âgés qui parlaient la même langue. Chaque jour Jon et ses nombreux animaux rencontraient Paul pour maintenir leur langue ensemble. Un jour, Paul est allé rencontrer Jon. Mais en arrivant, il a remarqué que la porte était ouverte. Quelque chose n’allait pas. Paul est entré. John s’était éteint sur son fauteuil. Un mois plus tard, un notaire est arrivé avec le testament. Jon avait laissé à Paul son perroquet comme cadeau. Ce dernier s’est mis à pleurer quand le perroquet a commencé à parler la langue !

Harrison Cartwright, Year 12

Allô P-p-puis-je parler à Monsieur Bordeaux ? Il est là ?

Ouais c’est moi, imbécile. Tu veux quoi cette fois ?

On doit c-c-causer en personne… si c’est possible. J’peux pas te le dire maintenant.

Dis-moi, personne n’écoute, t’as fait quoi ?

J’ai… J’ai fait une p’tite erreur.

Mais t’as fait quoi ?

Il est devenu silencieux pendant un moment.

Mon coffre-fort a disparu. Ils ont fouillé tout mon appartement, ma chambre est en désordre.

Et ils ont pris combien ?

Tout.

Monsieur Bordeaux tenait le coffre-fort sur ses genoux.

Je suis désolé, mais j’peux rien faire, mon ami.

Elishe Lim, Year 12

L’Estrade

Je pense. Je pense à la puissance, aux possibilités infinies, aux occasions que cette estrade fournit. Je m’émerveille. Je m’émerveille devant la beauté de cette scène boisée : ses pièces distinctives, ses caractéristiques élaborées soigneusement et ses changements prévisibles des couleurs comme une discothèque monochrome.

Je regrette. Je regrette des erreurs que j’ai faites, des signaux que j’ai manqués, des occasions que j’ai gâchées. « C’est votre tour. »

J’espère. J’espère que j’ai bien pensé, que j’ai apprécié le moment, que je n’ai pas de regrets, que je peu m’exprimer en lettres et nombres… « Échec et mat ! »

Joseph Oluwabusola, Year 12

Il nous reste 24 heures.

J’ouvre la porte doucement. L’air se faufile dans ma maison. Je me sens bien. Mieux que bien; je me sens à la fois en sécurité et libre.

Il nous reste 16 heures.

Je sens une légèreté dans l’air, mais aussi plein d’espoir et de joie. La tension constante a disparu.

Il nous reste 8 heures.

La nuit tombe. Il fait un noir sombre, mais je n’ai plus peur. Plus besoin de me retourner en marchant. Plus besoin de craindre pour ma vie quand je marche seule dans la rue.

Il ne nous reste plus d’heures.

La journée sans hommes s’est terminée, mais elle était magnifique.

Safiyah Sillah, Year 12

Je me suis baladé dans la rue avec mon chien remuant sa queue. Ce matin était calme ; j’écoutais seulement le son des oiseaux qui chantent. Le soleil a jeté un coup d’œil à travers les nuages. Soudainement, mon chien est commencé à aboyer, avec un sens de l’urgence. Le ciel et les nuages a confondent en une couverture grise. Les vague de gens qui voyagent m’a frappé comme un tsunami. Vite et impitoyable. C’est lundi, le temps est venu de mettre vos masques pour la semaine. Préparez-vous, mais n’inquiétez pas, les jours passeront avant vous le connaissez !

Teniola Ijaluwoye, Y12

FRENCH FLASH FICTION: THE SIXTH-FORMERS

Here are five brilliant ultra-short stories that were highly commended entries in the Years 12 and 13 section of our Flash Fiction Contest. Hope you enjoy them — more next week…

La nature d’aujourd’hui

Rivières scintillantes, et soleil chaud. Tu la sens dans tes os, la tendresse de la pluie de l’été. Que la vie est belle ! Tout ce que ton âme veut, ce n’est rien. Il vaudrait mieux rester ici, pour toujours. Tu sais que Mère Nature est avec toi.

Tu enlèves les lunettes et sens la saleté. « Sont bonnes, n’est-ce pas ?» dit le commerçant. Tu acquiesces et tu te tournes pour partir.

« Attendez, madame ! Vous avez oublié vos boîtes d’oxygène ! »

Tu fais demi-tour et tu te demandes pourquoi le monde est devenu si gris.

Jamilya Bertram, Year 12

L’habit ne fait pas le moine. Bien sûr ; ce serait toujours lui. Il est aussi parfait que sa photo. La façon dont ses yeux regardent les miens en dit plus que les mots ne le pourraient jamais. Je veux le tenir pendant qu’il pose ses bras sur moi, sans jamais lâcher prise. Une larme tombe sur mon visage. Nous parlons sans mots ; nous n’avons jamais eu besoin de mots pour parler. Deux garçons ne pourraient-ils pas être amoureux ? Je ne sais plus. J’éteins mon téléphone. Il n’est pas là, il n’était jamais là. Je suis seul.

Benjamin Fletcher (Y12)

Lors d’une soirée d’hiver au ciel ténébreux, une sinistre bête plane vers les égouts à la rencontre de son ami, le rat. La chauve-souris vient échanger avec son ancien complice son dernier délit.

“Bel ami qu’as-tu fait ces deux dernières années ?” interroge le rat.

“Ma chère vermine terrestre, j’étais occupée à répandre dans le monde une maladie plus destructrice que ta propre petite peste ! Actuellement en route pour mettre fin à l’homme je suis…”

“Félicitations !” répond le rat.

Soudainement, les eaux des égouts montent, causant un déluge, qui noient les deux créatures.

Nul parasite vaincra l’humanité.

Charles Blagburn (Y12)

Les colonnes blanches entre lesquelles un agent de sécurité lui a regardé soigneusement étaient immenses. Derrière une vitrine, les bijoux de son arrière-grand-mère brillaient et à côté desquels il y avait une photo avec du texte, racontant son histoire par les mots de ceux qui l’avaient détestée.

Il était si proche à ses racines, jusqu’à ce que les conservateurs aient éteint les lumières pour annoncer l’heure de fermeture. Tout à coup les yeux de son arrière-grand-mère ont disparu dans l’obscurité. En sortant avec ses propres yeux pleins de larmes, ses mains à son cœur, il a rempli de joie.

Jamie Hopkins, Year 12

Je suis allongé, rigide. De l’acier dans mon teint. Les doigts de glace s’agrippent à ma gorge. Un portrait de ma grand-mère me dévore de son oeil sévère.

Virginia Woolf croit que toutes les femmes sont liées, ourlées ensemble par un fil invisible. Alors pourquoi ai-je l’impression que le tissu du monde n’était pas assez élastique pour s’étirer jusqu’à moi? Mes pensées sont grandes aujourd’hui. Adultes. Dangereuses. Mais je ne suis pas une adulte, et certainement pas grande.

Les murs ont des oreilles. Peuvent-ils entendre mes pensées, aussi?

Mes pensées s’arrêtent.

Je crois voir ma grand-mère tourner la tête.

Allie Gruber (Y12)