SPOTLIGHT ON POLISH ROMANTICISM

by ALEKSANDRA MAJAK

Seldom does a literary epoch, philosophical movement, or aesthetic proposition divide readers as much as Romanticism. And no matter what we do or study, when our preferences and affinities with Romanticism are at stake, they tend to be an either/or option. When we think about the end of the eighteenth century, we are likely to recall (in tranquillity or not) the well-known image of a wanderer above the sea of fog from Caspar David Friedrich’s 1818 painting or one of J. M. W. Turner’s atmospheric landscape or marine paintings.

We are quick to talk about it all in bullet points: ‘extreme individualism’, ‘introspection over objectivity’, ‘return of the irrational and fantastical’, ‘poetical genius and inspiration’, ‘escapism’, ‘renewal of oral and folklore tradition’. The list goes on. Nevertheless, characterising the whole literary epoch by extrapolating from several, albeit influential, artworks or reading salient poems does not give a full picture. Ranging from the emotional unrest of the early Sturm und Drang movement in Germany; through the huge impact French Revolution had on all European art, to the metaphysical conundrums of the Russian poet and writer Alexander Pushkin, Romanticism is far from monolithic.

In England, the words that are often invoked to describe romantic principles are these of William Wordsworth from Lyrical Ballads (1798). Poetry, for him, is ‘the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings’ that ‘takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquillity’ [1]. Years later, in his seminal 1919 essay about the representation of feelings in modern verse, modernist poet T. S. Eliot would attack a long-dead Wordsworth by opposing an idealistic romanticism of tranquillity and modern unrest [2]. The Wordsworthian idea from The Prelude was indeed romantic. And here, we may use ‘romantic’ in its adjectival and colloquial sense that indicates — to follow OED — a certain quixotism, sentimentality, naivety, or idealism.

If Wordsworth saw the historical moment as ‘a glorious time’ full of the ‘events / Of that great change’, others had reasons to be less optimistic. The roots and ambitions of Romanticism differ from country to country. By this logic, only by exploring paths ‘less travelled by’ – to follow Robert Frost’s ironically mainstream line – can we widen our understanding of the period and maybe even challenge the myths surrounding ‘unified’ Romantic sensibility and so-called ‘organic form’?

The glory of honourable defeats

Romanticism might well be glorious in the grandiosity of its poetic aspirations but – in Polish literature – it was far from tranquil. After the subsequent partitions (1772, 1793, 1795) of Poland between neighbouring Russia, Austria, and Prussia the country was totally swindled and spend 123 years under occupation. So, formally, there was no country, and Poland was erased from the maps of Europe. The suggestively entitled painting Rejtan, or the Fall of Poland by acclaimed artist Jan Matejko depicts Partition Sejm in 1773 and Rejtan’s (the character on the right bottom corner) dramatic protest against it.

When twenty-year-old Matejko finished Rejtan in 1866, the painting gave rise to heated debate. With the still-fresh memory of the failed January Uprising (1863) hanging heavily in the air, the young painter decided to criticise the elites and their responsibility for Poland’s tragic political situation. Cyprian Kamil Norwid — a late-romantic poet — would, for instance, criticise the painting, saying that ‘Rejtan is a demon with a moustache’. The daunting situation had a lasting impact on the culture and even the current national anthem, composed in 1797, opens with the line: ‘Poland has not yet perished / So long as we still live’. Given the genre, ‘not the most optimistic or conventional opening’ — as one of my undergraduate students aptly observed.

One of the many problems with Polish romanticism is its self-perceived seriousness, its idealised self-image, its lack of critical detachment. All of these continue to impact today’s perception of national symbols that are too often prone to political manipulations. The prominent critic and scholar Maria Janion thought about these issues diagnosing, after 1989, the end of the Romantic paradigm. Still, if transformation brought Poland a free market, rapid economic development, and international mobility; ‘how would Poles define themselves when they had nothing to fight bravely against?’ [3]

Even if Polish writers shared and borrowed from all European traditions, the role ascribed to literature differed from its Western counterparts [4]. The poet was treated like a prophet, soothsayer or bard while poetry was read seriously and in the hope that it would have some causative power. It is common to refer to the well-known trio of Polish romantic poets – Adam Mickiewicz, Juliusz Słowacki, and Zygmunt Krasiński – as wieszcze narodowi, meaning ‘The Three Bards’.

Literature fights against oppression

Still, the oddest idea developed by Polish romanticism was ‘Poland as a Christ of Nations’ that made Roman Catholic Christianity a distinctive part of its cultural heritage. The canonical literary works of the time drew a parallel between Poland’s suffering and the suffering of Christ. This messianism was therefore used by Poles in their fight for eventually re-gaining independence in 1918.

In his late and unfinished poetic drama Forefather’s Eve, Mickiewicz would fortify this tradition. His hero, Gustav, is a typically self-absorbed romantic lover. Here, however, Gustav transforms into Konrad, who is determined to fight against oppression. Notice how the symbolic death and rebirth of the hero is represented graphically, as if alluding to the ancient genre of epitaph so the text that is inscribed on a tombstone or plaque.

Ironically, the title of Mickiewicz’s drama, Dziady, which established the idea of ‘Poland as a Christ of Nations’ comes from nothing other than… a Slavic pagan ritual! The ritual of dziady was a feast of commemoration of the dead now celebrated mostly, if not only, in Belarus. It also made it into the game based on Andrzej Sapkowski’s saga, The Witcher 3 where one of the quests is to meet the master of the ceremony and help villagers in addressing incoming souls.

Well-educated, well-read, having lived abroad, and determined to address ‘Young Friends’ who are ‘Strong in unison, reasoned in rage’, the great rivals Mickiewicz and Słowacki began their work with youthful enthusiasm. They set their youthful energy and rebellion against the inertia of their elders. Sometimes, like in my favourite romantic poem My Testament by Słowacki, both patriotism and youthful determination intertwined. Think, for instance, about the following passage. Now, you may even recognise Slowacki’s allusion to the forefather’s eve ritual.

But you that knew me well, in your reports convey

That all my younger years were for my country spent:

While battle raged, at mast I stood, be as it may,

And with the ship I drowned when vanquished down she went.

Oh that my friends at night together gathered be,

And this sad heart of mine in leaves of aloe burn!

And give it then to her who’s given it to me.

Thus mothers are repaid: with ashes in the urn.

Oh that my friends around a goblet sit once more,

And drink unto my funeral and their poor lot.

Be I a ghost, I will appear and join them or —

If God may spare me pain and torture — I shall not.

But I beseech you — there is hope while there is breath.

Do lead the nation with a wisdom’s torch held high,

And one by one, if needed be, go straight to death,

As God-hurled stones that densely over ramparts fly. [5]

The last stanza of the excerpt exemplifies how Slowacki urges his friends to sacrifice their lives in the fight for freedom. Moreover, years later, in 1943, Aleksander Kaminski would use Slowacki’s words for the title of his book Stones for the Rampart. Through the book we, yet again, see how authors echo the romantic vision of sacrifice as the story follows a group of young friends whose hopes, dreams, and joys of their early twenties are interrupted by the outbreak of the Second World War and the failure of the Warsaw Uprising. In his war movie Warsaw 1944 (available on Netflix) Polish director Jan Komasa borrows from romantic imagery, ideals, and myths. The English trailer gives a sense of this post-romantic symbolism.

The urgency of longing

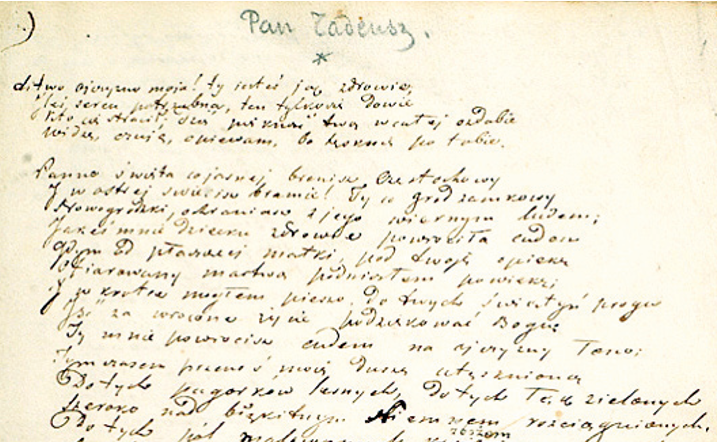

Sometimes poets would evoke political messages less directly, for instance, by adopting a nostalgic tone. One of the most well-known lines of Polish Romanticism comes from the epic poem Pan Tadeusz, written by Mickiewicz and published in Paris in 1834. The most recent English translation of the book – by the acclaimed translator and former Oxford student, Bill Johnson – is brilliant and gives the poem the freshness and dynamism that canonical works every so often lack if read within their own cultural circle. [6]

The epic, like all epics, begins in a serious, high-style tone that does justice to the author’s yearning for the missed Fatherland:

Lithuania! My homeland! You are health alone.

Your worth can only ever be known by one

Who’s lost you. Today I see and tell anew

Your lovely beauty, as I long for you.

The epic has the subtitle ‘The Last Foray in Lithuania’. Across twelve books, all written in the unique metre of the Polish alexandrine, Mickiewicz tells the feel-good, nostalgic story of the eponymous Sir Tadeusz. He is a young man from an upper class of nobility who returns from his studies abroad to an idyllic Soplicowo. In a way, the character of young Tadeusz enables Mickiewicz, as an author, to express his personal longing.

[…] Meanwhile, transport my yearning soul

Back to those wooded hills, those meadows wide

And green, that line the pale blue Niemen’s side;

Those fields adorned with many-colored grain

Where golden wheat and silvery rye both shine,

Where clover with its maidenly red blush,

White duck wheat, and amber rapeseed all grow lush,

Ribboned round by a green field boundary where

A tranquil pear tree nestles here and there.

Even if the scenery is indeed tranquil, the reader knows the backstory that makes such an idyllic description of nature into something more complex, and ambivalent, filled with juxtapositions that are not obvious at the first glance.

Full of national traditions, subtleties, and idiosyncrasies, much of Polish romantic poetry, epic, and drama was written against the grain of failed uprisings, buried hopes, tragic defeats, and longing for a lost fatherland as expressed by émigré writers. The well-known historian of Eastern Europe, Norman Davies, observed that the Polish political microclimate allowed ‘myths to flourish’. And since myths are known to have broad applications and functions, it is now fascinating yet dramatic to observe how the romantic ideas strongly embedded within Polish culture have or have not been used.

[1] More about the leading ideas and forms of European Romanticism can be found in a comprehensive book by Nicholas Roe, Romanticism: An Oxford Guide. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

[2] See https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/69400/tradition-and-the-individual-talent

[3] See the article by Stanley Bill in Being Poland : A New History of Polish Literature and Culture since 1918 ed. Czaplinski, P., Nizynska, J., Polakowska, A., & Trojanowska, T. (2019). Toronto, 2019.

[4] More about the political underpinnings of Polish Romanticism see: https://culture.pl/en/article/polands-unique-take-on-romanticism-why-is-it-so-different

[5] http://wolnelektury.pl/katalog/lektura/slowacki-my-testament

[6] See https://archipelagobooks.org/book/pan-tadeusz-last-foray-lithuania/