posted by Catriona Seth

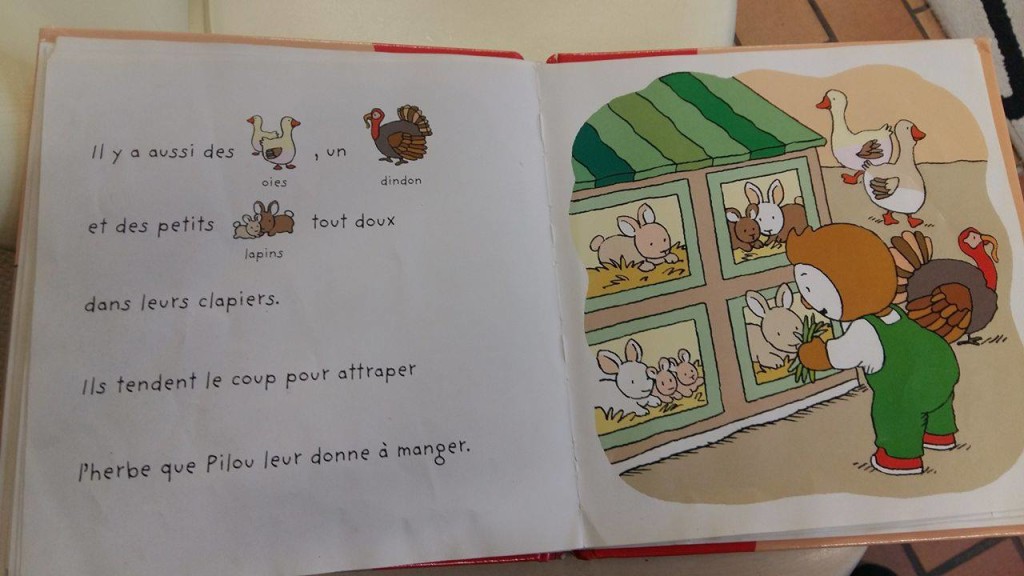

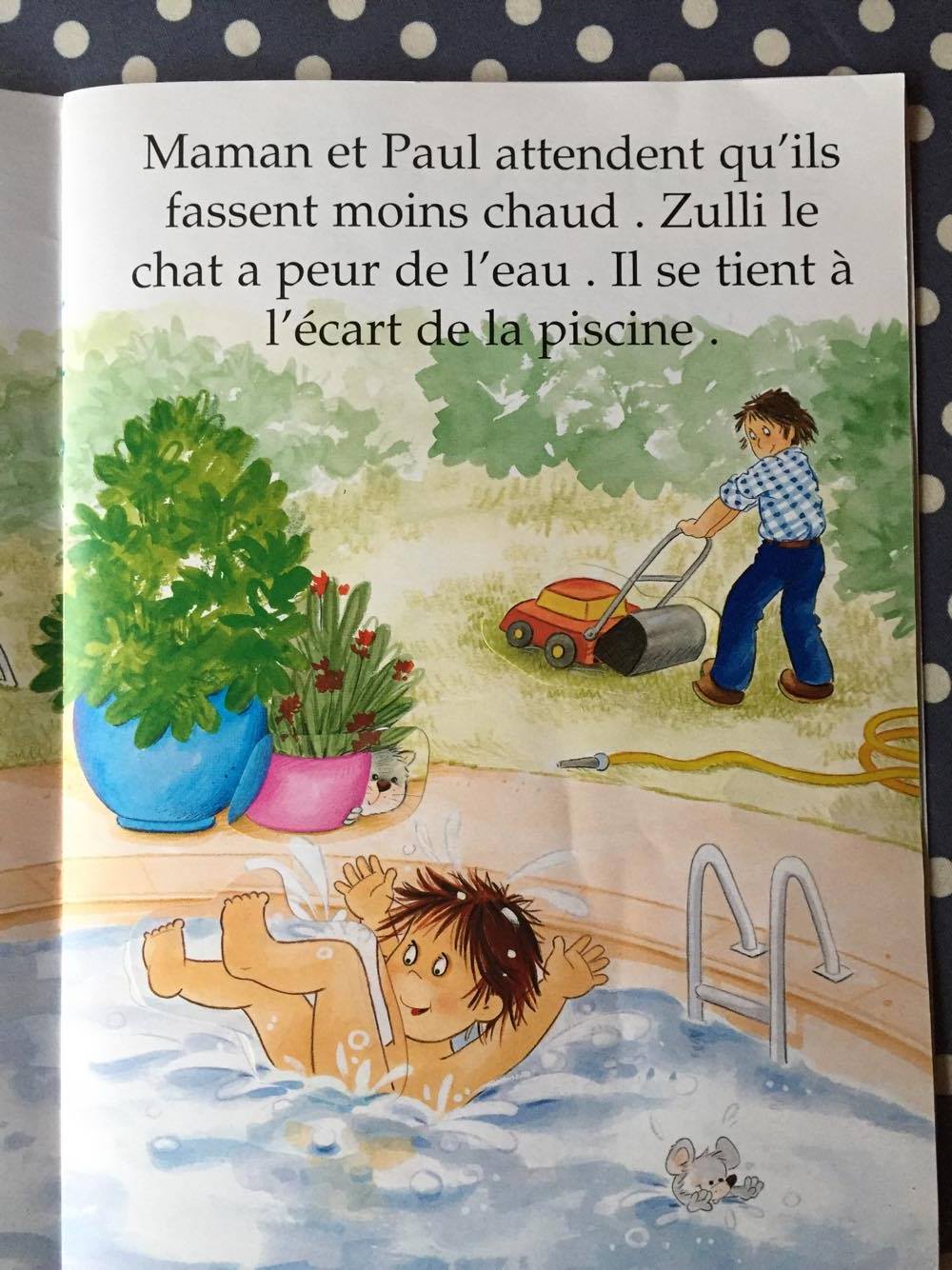

If you happen to be in France, there is one term you will see all over the place at this time of year: la rentrée. Obviously, it means the fact of re-entering… but what do you re-enter? ‘Papeteries’ or stationers and ‘Librairies’ or bookshops will give you a clue to one aspect of the ‘rentrée’ every schoolchild knows about: ‘la rentrée des classes’ or ‘la rentrée scolaire’, when everyone goes back to school. Nobel prize winner Anatole France relates a young boy’s thoughts and demeanour in his autobiographical Le Livre de mon ami, which was first published in 1885 : ‘Vivent les vacances, à bas la rentrée. Il avait le cœur un peu serré, c’était la rentrée. Pourtant, il trottait, ses livres sur son dos et sa toupie dans sa poche’. The spinning top in his pocket tells us a little about what games might have been usual at playtime in a nineteenth-century ‘cour d’école’. If he had come from Germany or parts of Eastern Europe, the young pupil might have been packed off for his first day at school with a ‘Schultüte’, a cone filled with sweets and small presents.

‘La rentrée’ is the time when everything picks up again after the summer. You will hear people of all ages and in all walks of life wishing each other ‘une bonne rentrée’. One of the specific aspects of French ‘rentrées’ is that they see the publication of a large number of books, particularly novels—there are 581 ‘romans de la rentrée’ out this year. This is what is known as ‘la rentrée littéraire’. Newspapers and magazines are full of suggestions about what to read: ‘les meilleurs romans de la rentrée’, ‘les romans les plus attendus de la rentrée’…

One of the books to watch is always Belgian author Amélie Nothomb’s new offering. She produces one book a year, regular as clockwork, and it comes out in time for ‘la rentrée littéraire’. Last year’s bore the same title as a fairy-tale by Charles Perrault, Riquet à la houppe (Ricky with the tuft) and is a fun variation on the ‘beauty and the beast’ theme. Like many of her novels, it is short and easy to read. This year’s offering, her 26th, is called Frappe-toi le cœur, a reference to a twelve-syllable line of verse (‘un alexandrin’) by romantic poet Alfred de Musset ‘Ah! Frappe-toi le cœur, c’est là qu’est le génie’: ‘Ah! Beat your heart, that is where genius lies’. He was suggesting that true genius involves feeling and not just thought. I have included his poem at the bottom of the page for those who want to read it.

And here is a little exercise on ‘rentrer’, the verb, and ‘rentrée’ the noun. See if you can fill in the blanks using the noun where appropriate and any of the following tenses for the verb: the ‘passé composé’, the ‘présent de l’indicatif’, the ‘futur simple’ and the ‘participe présent’.

Comme c’est la __________ Jeanne a un nouveau cartable. Cette année elle __________ à l’école primaire. Son frère Pierre est plus âgé qu’elle : il __________ au lycée l’année prochaine. Leur mère est une grande lectrice et s’intéresse aux romans de la __________. Après avoir déposé Jeanne à l’école, elle __________ chez elle avant de partir travailler. En __________ dans l’immeuble, elle a croisé son voisin de palier qui lui a souhaité une bonne __________. Il était très souriant : il venait d’apprendre qu’il allait avoir des __________ d’argent inattendues grâce à un petit héritage.

Answer: rentrée – est rentrée/rentre – rentrera/rentre – rentrée – est rentrée/rentre – rentrant – rentrée – rentrées

You will have noticed the meaning of ‘rentrée(s)’ in the final sentence is a different one: ‘Avoir une rentrée d’argent’ means to come into some money, not necessarily, as here, through an inheritance.

A mon ami Edouard B.

Tu te frappais le front en lisant Lamartine,

Edouard, tu pâlissais comme un joueur maudit ;

Le frisson te prenait, et la foudre divine,

Tombant dans ta poitrine,

T’épouvantait toi-même en traversant ta nuit.

Ah ! frappe-toi le cœur, c’est là qu’est le génie.

C’est là qu’est la pitié, la souffrance et l’amour ;

C’est là qu’est le rocher du désert de la vie,

D’où les flots d’harmonie,

Quand Moïse viendra, jailliront quelque jour.

Peut-être à ton insu déjà bouillonnent-elles,

Ces laves du volcan, dans les pleurs de tes yeux.

Tu partiras bientôt avec les hirondelles,

Toi qui te sens des ailes

Lorsque tu vois passer un oiseau dans les cieux.

Ah ! tu sauras alors ce que vaut la paresse ;

Sur les rameaux voisins tu voudras revenir.

Edouard, Edouard, ton front est encor sans tristesse,

Ton cœur plein de jeunesse…

Ah ! ne les frappe pas, ils n’auraient qu’à s’ouvrir !

Alfred de Musset (1810-1857)

posted by Simon Kemp

posted by Simon Kemp

![‘… a parler, bien sonere et parfaitement escrire douce frances qu’est la plus belle et la plus gracious langage et la plus noble …’ [A detail from a manuscript of the Manière de langage, Cambridge University Library, MS Dd.12.23, f. 67v.]](https://farm4.staticflickr.com/3847/14940771507_dc23047502_o_d.png)

Thanks for these most interesting examples. I agree that Trevien is by far the best of the translators here who try to preserve poetic form, but there are still some terrible word choices: for instance, haunting for mystique is a mistranslation, pure and simple. There’s no good reason for it, either, since the syllabication of the two words is the same.

Which brings me to your point about there being no objective standards by which to judge better and worse translations of poetry. It seems fairly clear that any translation which distorts a poem’s meaning is a worse translation than one which doesn’t. So, my bias, if you want to call it that, is for translations that preserve the meaning, including, insofar as possible, connotations, associations, and nuances, over form.

For me, then, Aggeler is far and away the best translator of Baudelaire sampled here, and I would also disagree that no one could tell from looking at his translation that Baudelaire has written a sonnet. The stanzaic structure and number of lines will strongly suggest the form to any reader who knows the technical requirements of the sonnet in the first place.

I also think that the best way to read foreign-language poetry is in a bilingual edition with the original and the translation on facing pages. Even if one has only “schoolboy French”, one can get a sense of the form, meter, and rhyme scheme from Baudelaire’s poem, and also, via a translation such as Eggeler’s, grasp the meaning.

P.S. Perec omitted the letter “e” (no “Googling” involved).

I have just published my own translation of ‘Les Fleurs du Mal’, available on Amazon in three editions. Here is my version of Les Chats, which I hope compares favourably with the above translations:

When ardent lovers or austere scholars grow old,

Both are disposed to love, in their maturity,

The powerful, gentle cat, pride of the family,

Who like them loves to sit, and like them shuns the cold.

Friends of both science and of sensuality,

Cats like to seek the silent horror of the dark;

As stallions of Erebus they’d have made their mark,

Had they to servitude inclined their dignity.

As they dream, they adopt the noble attitude

Of a great sphinx, recumbent in deep solitude,

Seeming to dream forever in its native land.

From their generous loins mysterious sparks arise,

And particles of gold, like grains of finest sand,

Reflect like stars behind their enigmatic eyes.

I have made one or two amendments to the above translation. I have changed “disposed” to “inclined” and and have made slight alterations to the two tercets, especially the last line which now has a more literal translation.

LVI. – CATS

When ardent lovers and austere scholars grow old,

Both are inclined to love, in their maturity,

The powerful, gentle cat, pride of the family,

Who like them loves to sit and like them shuns the cold.

Friends of both science and of sensuality,

Cats like to seek the silent horror of the dark;

As stallions of Erebus they’d have made their mark,

Had they to servitude inclined their dignity.

As they sleep, they adopt the noble attitude

Of the great sphinx, recumbent in deep solitude,

Seeming to dream forever in its desert land;

From their abundant loins magical sparks arise,

And particles of gold, like grains of finest sand,

Confusedly bestar their enigmatic eyes.