posted by Simon Kemp

(This is the fifth post in an occasional series asking and answering a key question about the books and films on the A-level French syllabus. You can find the others by clicking the ‘A-level texts’ tag at the end of this post.)

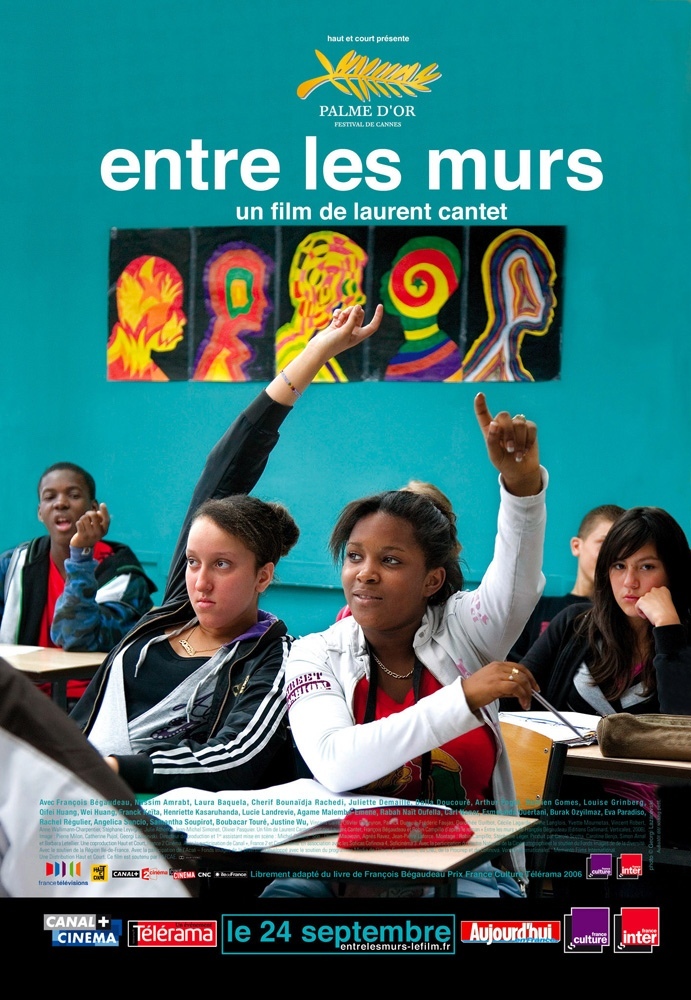

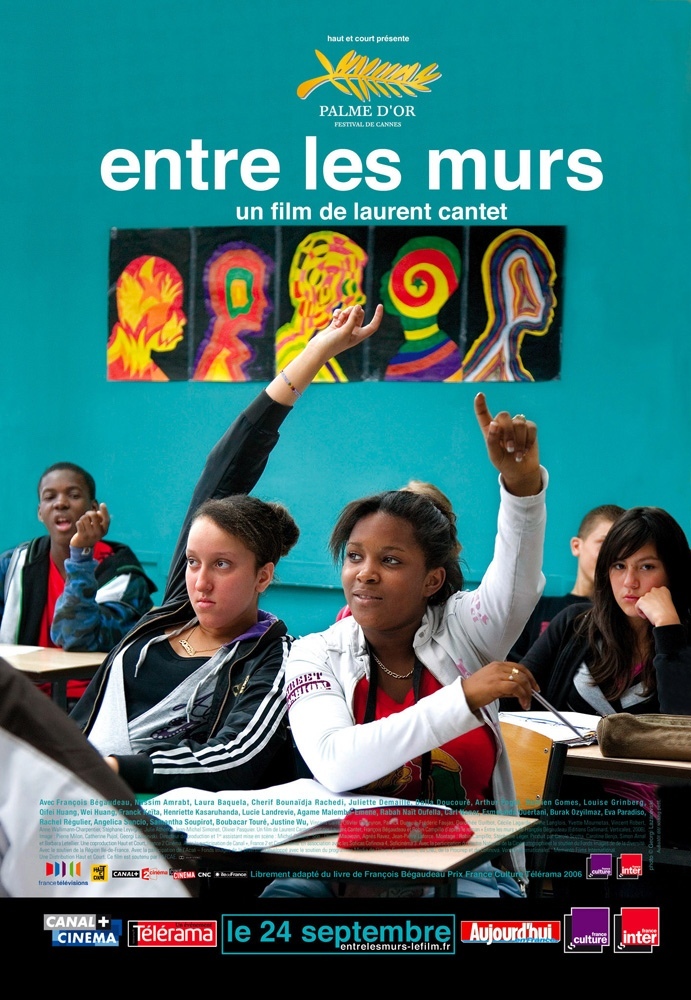

Entre les murs (The Class) is a 2008 film about a class of teenagers in an inner-city Paris school and their teacher, M. Marin. It stars François Bégaudeau as the teacher, who also wrote the screenplay, adapted from a novel he wrote inspired by his own teaching experiences.

If you don’t know the film, here’s a subtitled version of the trailer:

https://youtu.be/t8HWJqgMAhU

The turning point in the film, and one of the most dramatic moments in the story, centres on a single word. Since the start of the film, M. Marin has had a teasing, sometimes slightly mocking attitude towards the students, which has been met with a healthy disrespect coming back at him. On this day, though, he pushes things too far and openly insults two of his students. A line has been crossed, the class is in uproar, and there will be serious consequences for teacher and pupils alike.

To set the scene: Esmerelda and Louise are the class representatives, who, as part of their role, get to sit in on teachers’ meetings. The previous day they attended such a meeting and annoyed M. Marin with their whispering and giggling. Today in class he discovers that they have passed on sensitive information from the meeting to their classmates, including some negative remarks he made about one of them. As the mood in the class turns mutinous and M. Marin gets increasingly flustered, he starts to criticise the two girls for how they behaved during the meeting, and the following exchange occurs:

Louise : Mais nous, on a fait juste notre rôle, hein, rien de plus !

Esmerelda : On dit ce qui s’est passé au conseil de classe.

M. Marin : Ouais, bien sûr, ouais. Je n’avais pas cette impression-là, moi. Quand je vous ai vues ricaner là, un moment pendant le conseil, moi j’ai eu un peu mal, ouais ? Ça m’a fait un peu mal pour vous.

Esmerelda : Ah, bon ?

M. Marin : Et j’ai trouvé que c’était ni le lieu ni le moment de le faire. Et que c’était pas très sérieux pour tout dire, d’accord ?

Esmerelda : Ouais, ben, ça dérangeait personne en tout cas.

M. Marin : Ah, mais si ! Si, si. Ah, non, non, non, non, non. Moi, ça me dérangeait, et je crois en plus pouvoir dire que ça dérangeait des autres aussi.

Esmerelda : Non, non, non. Ça dérangeait que vous.

M. Marin : Si, si. Moi, je suis désolé, mais rire comme ça en plein conseil de classe, c’est ce que j’appelle une attitude de pétasses.

Louise : Quoi ?

Esmerelda : Eh, mais vous pétez un câble ou quoi ?

What did he just call them? Here’s how the English subtitles translate the dialogue:

We’re just doing our job. / Yeah.

We say what happens at the staff meeting.

Yes, of course.

I didn’t get that feeling

When I saw you two giggling, I felt bad.

I felt bad for you.

Really? / It was not the time or the place to giggle.

That’s not responsible.

Well, it didn’t bother anyone.

Yes, it did.

It bothered me and the others as well. / No way.

To giggle during a meeting like that is behaving like a slut.

What?

Are you out of your mind?

The English insult in the subtitles certainly works in the film. It would believably trigger the student outrage against the teacher and the disciplinary proceedings that follow. But is it right?

When they come to talk about the insult later on, the student and the teacher have very different ideas about what the word means:

Esmerelda : Déjà, pour moi, pétasse, ça veut dire prostituée.

M. Marin : Une pétasse, c’est une fille pas maligne qui ricane bêtement.

And dictionaries also disagree. The Petit Robert defines pétasse as :

prostituée [employé le plus souvent comme injure]

while Le Dictionnaire de la Zone, which specializes in up-to-the-minute slang usage, says it means :

femme d´allure vulgaire, provocante, aguichante

which, while maybe not as innocent as M. Marin’s own definition of the word, is closer to his version of it than it is to Esmerelda’s.

So it does seem that M. Marin’s insult, while it’s definitely inappropriate language for the classroom, might genuinely mean different things to different people, especially if they’re people of different ages and backgrounds like M. Marin and Esmerelda. He thinks he’s accusing Esmerelda and Louise of behaving like dumb, giggling girls; they hear him calling them prostitutes.

Pity the poor translators who had to try to get these nuances across in the English subtitles. I think we can probably agree that they didn’t quite manage it, and I think we can also probably agree that we couldn’t have managed any better if it had been up to us to do it. Sometimes there simply is no word in English that will translate the full meaning of a French one, with all its connotations and ambiguities. Lucky for us, then, that we can deal with the French words directly, without having to rely on the subtitles!