This post was originally published on the Creative Multilingualism blog. Creative Multilingualism is a four-year AHRC-funded programme investigating the interconnection between linguistic diversity and creativity. Regular readers of Adventures on the Bookshelf will remember Prof. Matthew Reynolds’s earlier post about translations of Jane Eyre. In this post, Prof. Reynolds talks about the process of mapping different translations of the novel.

Mapping Jane Eyre’s translations is a challenge, on several fronts. First, where do you locate a translation on a map? It will have been done by a translator in a certain place, or places; but then it may have been published somewhere else; and it can be read wherever there is a reader who understands its language – which is, in many cases, pretty much anywhere.

Usually, we can find no information about where a translation has been written (often translations are anonymous). We don’t want to attach the translations to particular nation states, because languages don’t correspond to nation states: think of the many languages spoken in India (or indeed the UK), or the many states that have Spanish, French or Portuguese as official languages. So we have opted for the place of publication – not endeavouring to put boundaries around the territory inhabited by a translation, but showing the point from which it came out into the world.

Yet where exactly is a place of publication? For one set of maps, which allow readers to trace the development of the cover images in connection with the place and time of publication, we have used the publishers’ street addresses (this necessitated much careful work on the part of the project’s researchers – and caused some anguish!). Here we find a by-product of looking at the world of books through the lens of Jane Eyre: tracking the translations, we discover the bits of cities where publishers cluster, and find harmonies between the books’ designs and their locales. But for the general maps, which allow us to see and understand the spread of Janes across the world, street addresses seemed too specific. For these visualisations, the city seemed the right unit of location.

When I made this theoretical decision, I hadn’t quite understood the relationship between the computer-magic of Digital Humanities and the mind-numbing, slow, human labour that lies behind it. Once you know a translation’s place of publication, the computer can do quite a good job of assigning latitudes and longitudes to the given names. But not a perfect one: it can’t know if you mean Paris (France) or Paris (Texas), the Tripoli in Libya or one of the lesser-known Tripolis in Lebanon or Greece. And you can’t know when it is going to make a mistake – which means that every point needs checking by human eye and hand. In the case of Jane Eyre the number of points that have needed checking (so far) is 543.

But latitude and longitude still do not amount to a city. For that, you need to find the outline of each city and paste it onto your map. In our case, that meant 171 cities from Addis Ababa to Zutphen. You find the outline of a city in a long list called a ‘Shape File’; and there are separate Shape Files maintained by every State. So you go to the Shape File for India and find Ahmedabad; then you go to the Shape File for Syria and find Aleppo, and so on. And on. The process is not so very painful when you are dealing with Berlin or Rome; but when it is Dushanbe in Tajikistan, or Kaifeng in China (written in non-alphabetic characters) you feel your life draining away as you struggle to be sure you have pinpointed the right place.

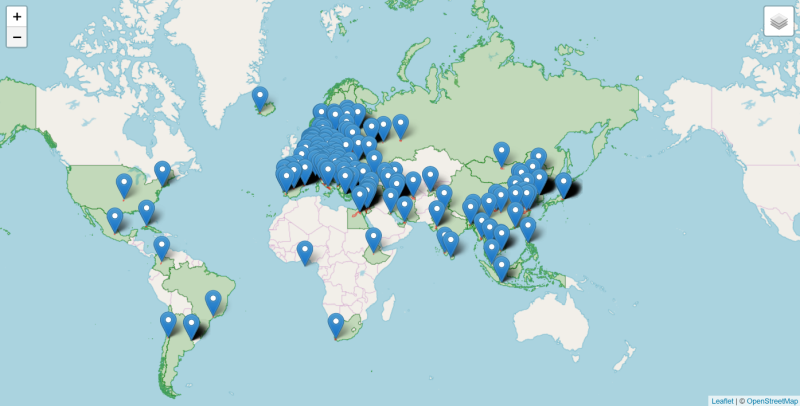

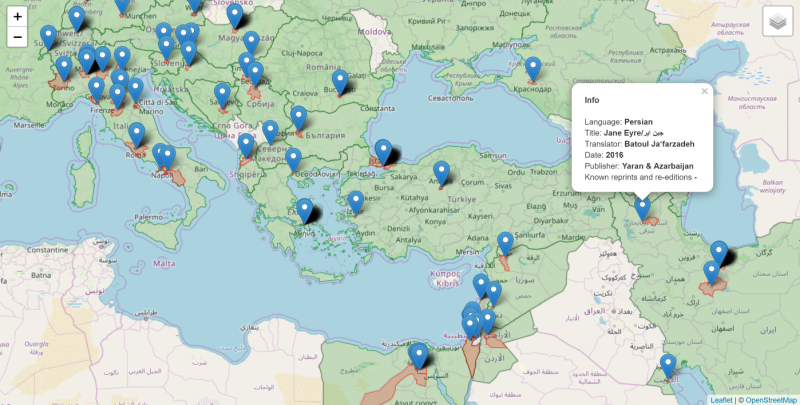

Then, after days of labour, the moment of magic, when you are suddenly able to witness the spread of Jane Eyres across the world, like this:

Or zoom in for a more detailed view, like this:

And this is only the beginning. The maps that we are currently working on organise the translations according to region and language, allowing a more analytical understanding of the processes at work; and they also show the translations unfolding year by year. So now (or, soon) you will be able to see before your eyes the startling spread of Jane Eyre translations that had already happened by 1850: Berlin, Brussels, Paris, St Petersburg, Stuttgart, Grimma, Stockholm, Groningen and – Havana!