We have just launched our annual competitions in French and Spanish. Details are below. If you have any questions please contact schools.liaison@mod-langs.ox.ac.uk. We look forward to reading your entries! Bonne chance! ¡mucha suerte!

Spanish Flash Fiction Competition

Did you know that the shortest story in Spanish is only seven words long? Here it is:

‘Cuando despertó, el dinosaurio todavía estaba allí’ (Augusto Monterroso, “El dinosaurio”).

Write a story in Spanish of not more than 100 words, and send it to schools.liaison@mod-langs.ox.ac.uk by noon on Friday 30th March 2018 with your name, age and year group, and the name and address of your school. A first prize of £100 will be awarded to the winning entry in each category (Years 7-11 and 12-13), with runner-up prizes of £25. The judges will be looking for creativity and imagination as well as good Spanish! The winning entries will be published on our website.

French Film Competition

The Department of French at Oxford University is looking for budding film enthusiasts in Years 7-11 and 12-13 to embrace the world of French cinema. To enter the competition, students in each age group are asked to re-write the ending of a film in no more than 1500 words. You can work in English or French. We won’t give extra credit to entries written in French – this is an exercise in creativity, rather than a language test! – but we do encourage you to give writing in French a go if you’re tempted, and we won’t penalize entries in French for any spelling or grammar mistakes.

The judges are looking for plausible yet imaginative new endings, picking up the story from the point specified (see below). There are no restrictions as to the form the entry might take: screen-play, play-script, prose, prose with illustrations. We’d also love to see filmed entries (e.g. on YouTube): feel free to experiment!

For the 2018 competition we have chosen the following films for each age bracket:

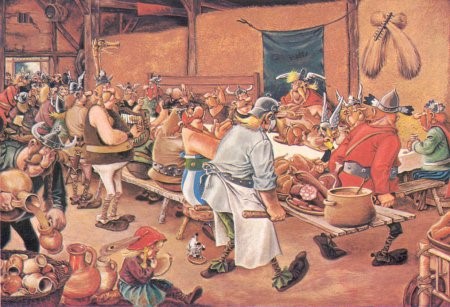

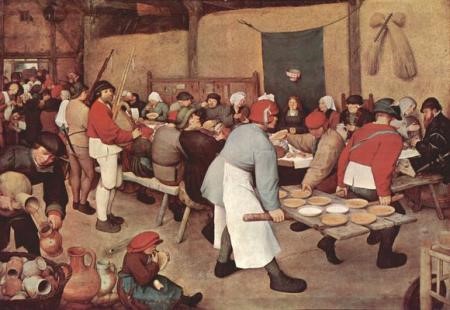

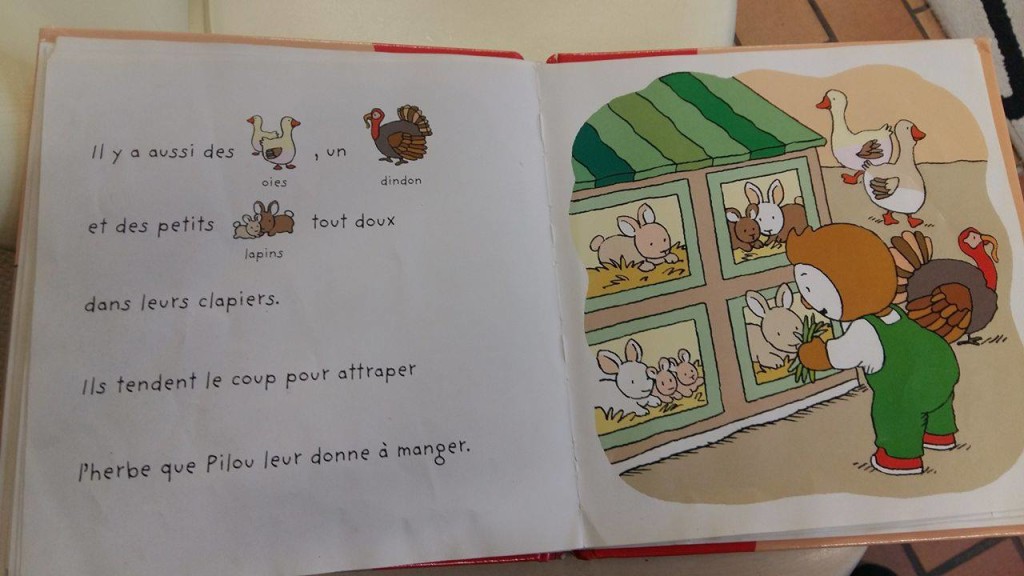

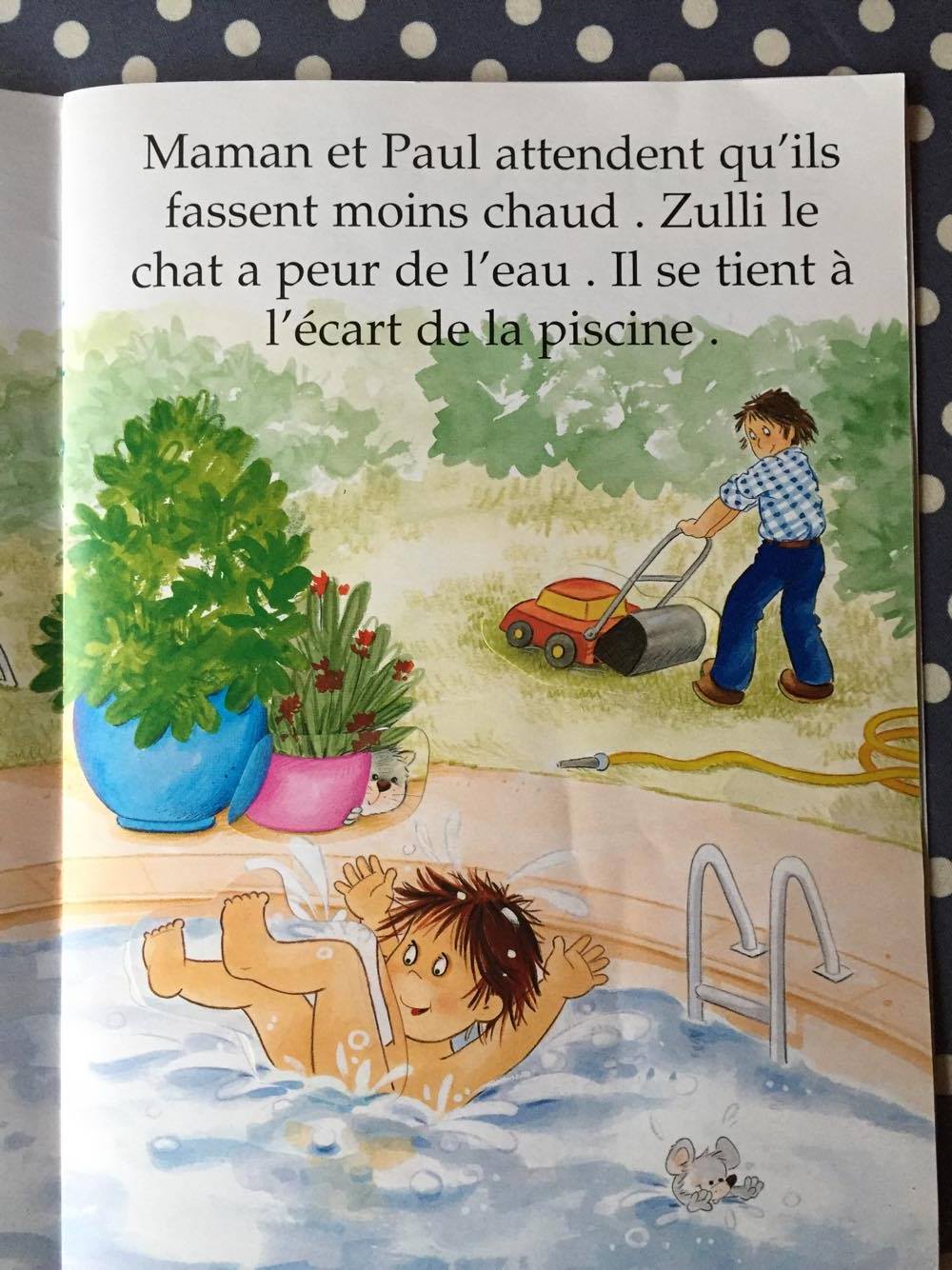

- Years 7-11: Une vie de chat (2010, dir. Jean-Loup Felicioli and Alain Gagnol)

- Years 12-13: Des Hommes et des dieux (2010, dir. Xavier Beauvois)

A first prize of £100 will be awarded to the winning student in each age group, with runner-up prizes of £25.

Your re-writing must pick up where the film leaves off, from the following points:

- Une vie de chat: from 49:20, when Nico says: ‘Allez, accroche-toi bien Zoë’.

- Des Hommes et des dieux: from 1:38:50, where Christian says ‘J’ai longtemps repensé à ce moment-là…’

Here are the trailers, to give you a taster:

DO’S AND DON’TS!

- DO keep to the word limit (1500 words)! Going over will lead to disqualification.

- DO use your imagination, and present your re-writing in any format you like – essay, screenplay, short film, storyboard, etc…. There is nothing stopping you from watching the ‘real’ ending and then modifying it as you see fit. Indeed, you might find this helpful. We’re looking for creative, entertaining and inventive new endings, which address as fully and plausibly as possible the strands of the story that are left unresolved at the end-points we’ve specified above.

- DO send in (through your teacher) individually named submissions. If you work in a group, the entry must still be sent under one name only: this is just to ensure as much as possible parity and fairness between entries, and to avoid any distinction between smaller and larger groups. There is a limit of 10 entries per school per age group.

- DO make sure you give your teacher enough time to approve and forward your submission!

- DON’T worry about which language you write in – and if you write in French (which we encourage, if you would like to), remember we do not penalise grammatical errors or spelling mistakes.

- DON’T forget to include a filled-in cover-sheet, signed by your teacher. Without this, your entry will not be judged.

- DON’T worry if you’re at the lower end of your age-range (especially Years 7 and 8). We particularly encourage entries from younger students, and we’ll take your age into account when judging your entry.

Where can I or my school/college get hold of the films?

The DVDs are readily and affordably available via Amazon (http://www.amazon.co.uk or http://www.amazon.fr). The films may also be available through legal streaming services (e.g. Amazon Prime, Google Play, or Blinkbox).

How do I send in my entry?

We’d like all your school’s entries to be submitted via your teacher please. Ask your teacher to attach your entries to an email, along with a cover sheet, which you can download here, and send it to french.essay@mod-langs.ox.ac.uk by noon on 31st March 2018. NB, to avoid missing the deadline, we suggest that you aim to give your teacher your entry and completed cover sheet by 24th March at the latest.

Good luck!

![‘… a parler, bien sonere et parfaitement escrire douce frances qu’est la plus belle et la plus gracious langage et la plus noble …’ [A detail from a manuscript of the Manière de langage, Cambridge University Library, MS Dd.12.23, f. 67v.]](https://farm4.staticflickr.com/3847/14940771507_dc23047502_o_d.png)

posted by

posted by

posted by Simon Kemp

posted by Simon Kemp