posted by Simon Kemp

I know from my students that for many people wanting to have a first go at reading a book in a foreign language, translations of J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter novels are the gateway to reading books in French. They’re a good place to start: if you’re familiar with the stories already from the books or films in English, then you’ll always have a rough idea what’s going on if the language gets tricky, plus it’s always entertaining to find out how a Crumple-Horned Snorkack or a Dirigible Plum comes out in a foreign language. (It would be good if Harry Potter were your first step towards trying a book by an actual French person, rather than your final destination, though, as I sometimes feel when I see it as the sole text cited on a personal statement as evidence of someone’s burning desire to study French culture…) Anyway, because you know the story already, and because it’s one of the trickiest and most interesting pieces of English-to-French translation of recent years, let’s head back to the École des sorciers in Jean-François Ménard’s translation for a second look.

Voldemort’s real name, as revealed in the climax of The Chamber of Secrets, is Tom Riddle, which, with the aid of his middle name, Marvolo, can be dramatically anagrammatized from

TOM MARVOLO RIDDLE

into the sentence

I AM LORD VOLDEMORT.

I remember thinking at the time that this was a lucky break for him. Only a couple of letters short and he’d have had to make do with

ORVILLE DOORMAT

as his evil alter-ego, which would have made the task of assembling a power-hungry army of ruthless dark wizards that bit more difficult.

If only, though, J. K. Rowling had invented an anagram that smoothly converted one name into the other. That ‘I AM’ at the beginning makes the big reveal into an English sentence, and an English sentence that can’t be translated into a foreign language without the whole puzzle falling apart. What is the poor translator to do?

One option is to do nothing. The Croatian, Portuguese and Polish translations of Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets give Voldemort’s name as Tom Marvolo Riddle, and then do the anagram sentence in English, as ‘I am Lord Voldemort’, with an explanation for their readers. The Korean and Japanese versions transliterate ‘Tom Marvolo Riddle’ into their own alphabets (톰 마볼로 리들 and トム・マーボロ・リドル), making it impossible to perform a new anagram in their own language or demonstrate the original one in English. Even if you’ve never seen the Korean alphabet before in your life, you can tell that 나는 볼드모트 경이다 (‘I am Lord Voldemort’, as it appears at the end of the Korean translation) is not an anagram of 톰 마볼로 리들.

Many translations, though, go for the more challenging option of changing the name to create an anagram that works in their language. So, in Italian, Tom Riddle is Tom Orvoloson Riddle (an anagram of “Son Io Lord Voldemort“), in Spanish he is Tom Sorvolo Ryddle (anagram of “Soy Lord Voldemort“), and in Icelandic, he is Trevor Delgome (anagram of “Eg er Voldemort”). (Incidentally, if you’re wondering where I got all these from, they’re all here, along with translations into thirty-seven languages of the names of all the major characters.)

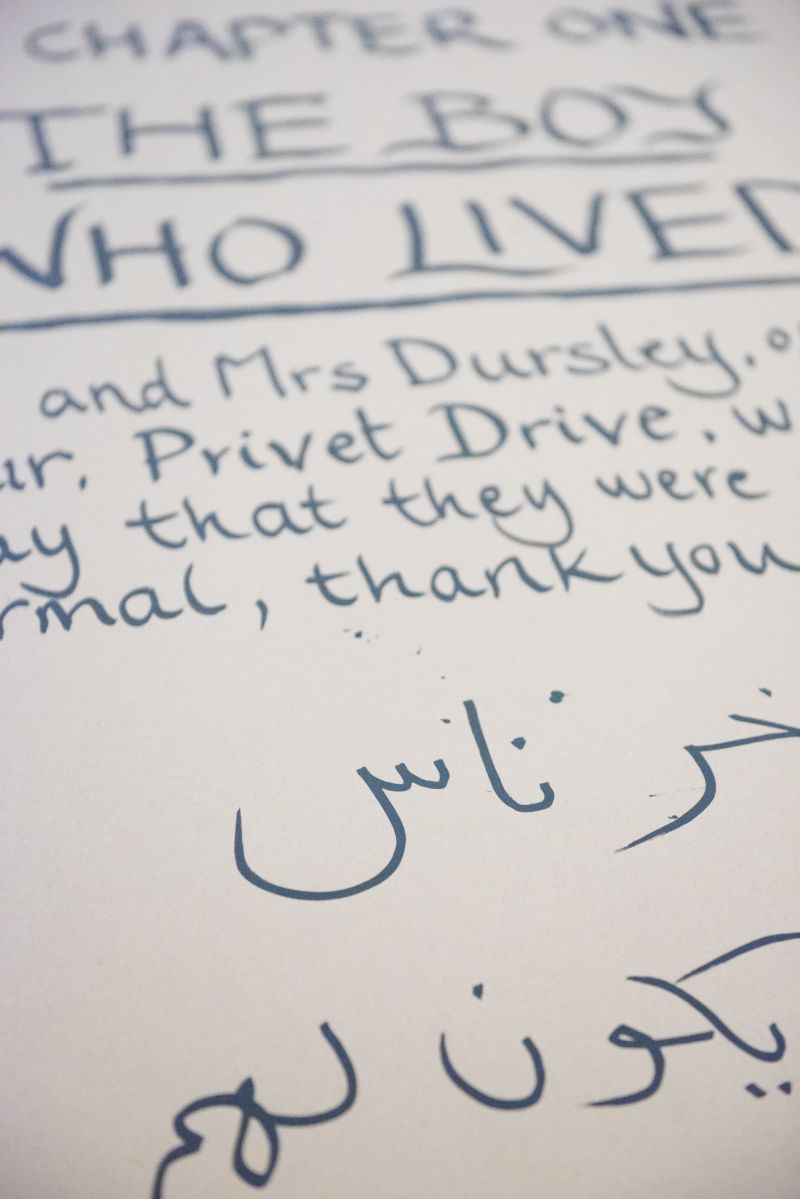

So what does Ménard do in his Harry Potter et la chambre des secrets? Well, he takes the more ambitious option and goes for an anagram that will work in French. The sentence he wants to reveal at the climax of the story is

JE SUIS VOLDEMORT

and so the name that replaces Tom Marvolo Riddle in the story is, wait for it…

TOM ELVIS JEDUSOR.

That’s right, Voldemort’s middle name, if you’re a French reader, is Elvis.

It’s actually cleverer than it may look. Ménard has managed to give Tom a real name for his middle name, unlike Rowling’s ‘Marvolo’, which looks suspiciously cobbled-together from the left-over letters she had after she’d come up with ‘Tom’ and ‘Riddle’. And ‘Jedusor’ is a phonetic spelling of ‘jeu du sort’, a phrase that means somewhere between ‘twist of fate’ and ‘game of chance’, and which perhaps also has undertones of the phrase ‘jeter un sort’, to cast a spell. Ménard weaves the meaning of the name into his story, making the Riddle House into La Maison des Jeux du Sort, and also has Voldemort himself tell Harry: ‘Tu crois donc que j’allais accepter le “jeu du sort” qui m’avait donné ce nom immonde de “Jedusor”, légué par mon Moldu de père?’.[‘Did you think I would accept the twist of fate that gave me the foul name Jedusor, bequeathed to me by my Muggle father?’] – a slight variation of Rowling’s original that helps to anchor Ménard’s new wordplay into the story.

And yet… and yet… Elvis? It has to be said that the name injects a rather incongruous element of rhinestone jumpsuits and Las Vegas glamour into Voldemort’s character. It also rather hilariously illustrates the perils of translating a story before the author has finished writing it. As you may remember, in Rowling’s English-language original, the name Marvolo turns up again in the sixth volume. Voldemort has in fact been named after his grandfather, the vile, abusive, squalid and half-insane dark wizard, obsessed with his aristocratic descent from Salazar Slytherin, who goes by the name of Marvolo Gaunt. And yes, in Harry Potter et le Prince de sang mêlé, penultimate volume of the French saga, we meet a vile, abusive, squalid and half-insane dark wizard, obsessed with his aristocratic descent from Salazar Serpentard, who does indeed go by the name of Elvis.