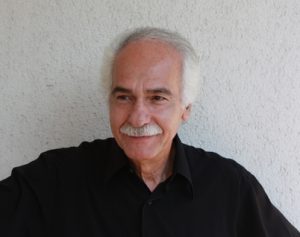

To celebrate publication of the new critical edition of Franz Kafka’s final, unfinished novel Das Schloss (The Castle), Carolin Duttlinger and Barry Murnane from the Oxford Kafka Research Centre hosted a day of activities with sixth-form students, two student workshops on editing and adapting Kafka, and a podium discussion to discuss the legacy of the novel. The day-long event brought together specialists from Oxford, Roland Reuß and Peter Staengle, and award-winning playwright Ed Harris, who recently adapted the novel for BBC Radio 4. In this blog post Barry Murnane, Associate Professor in German at St John’s College, introduces Kafka’s novel.

Das Schloss is not exactly the most obvious introduction to Kafka’s works. Written over a period of about seven months in 1922 while Kafka’s health was deteriorating (he had been diagnosed with what was probably tuberculosis several years earlier), Das Schloss is a rambling narrative that tells us how a protagonist known only as K arrives in a snow-covered landscape dominated by a castle and has to find his place in the local community:

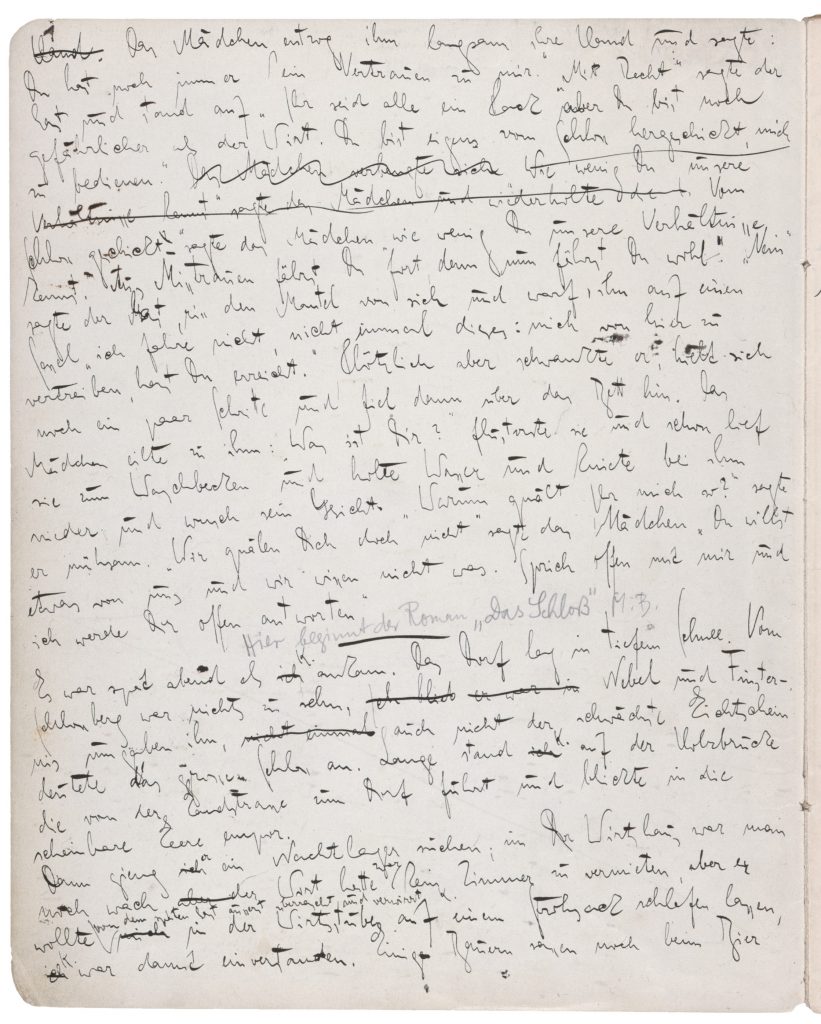

“It was late evening when K arrived. The village lay deep in snow. There was nothing to be seen of the Castle Mount, mist and darkness surrounded it, and not the faintest glimmer of light showed where the great castle lay. K. stood on the wooden bridge leading from the road to the village for a long time, looking up at what seemed to be a void.” (Franz Kafka, The Castle, transl. Anthea Bell. Oxford: OUP, 2009, p5)

Calling himself a “Landvermesser”, or “surveyor”, K finds himself in the middle of a society that is apparently dominated by a gigantic bureaucracy and he becomes involved in constant conversations with the locals trying to understand how this bureaucracy works.

For one reason or another, K never seems to ‘arrive’, however, and ends up constantly walking and talking in circles. On the one hand, he seems blameless because the castle authorities are not exactly forthcoming with any information. On the other hand, K appears at least partly responsible for his failure in that he treats the locals as little more than stepping stones on his way to the castle, including a potential lover called Frieda. It’s unclear how the novel would have ended: Kafka’s friend and first editor, Max Brod, says that Kafka told him on his deathbed how the novel was meant to finish with K being ‘accepted’ into the Castle and its community, but it seems a long way to go before K. would be accepted anywhere, never mind by the Castle authorities. Instead, we see a novel project trailing off into a “scheinbare Leere”, the seeming void, that K looks into at the start of the novel.

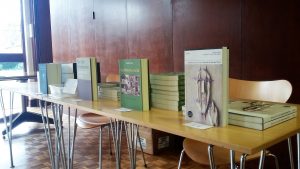

Thanks to the new critical edition of Das Schloss edited by Peter Staengle and Roland Reuß and published by the Stroemfeld-Verlag we now get a real sense of how Kafka actually wrote. Their edition reproduces the exact manuscript alongside an easy-to-read transcription, warts and all. The new edition is ground-breaking, but it puts an emphasis on scholars to make the overload of information it provides accessible. There is no easily consumable narrative of K against the Castle: we see passages where K is a less than positive hero figure, stubbornly refusing to actually listen to what people are telling him and treating women with little respect. One interesting thing is that the material of the manuscript itself shows no real sign of a struggle as Kafka begins to run out of steam with the project: the ductus of his handwriting remains smooth, flowing, perhaps even more so than at the start.

It is astonishing how relevant Kafka’s discussions of bureaucracy and social life in The Castle still are. With Oxford German Studies looking to build up to the centenary of Kafka’s death in 2024, the new edition of the novel is an ideal opportunity to discuss Kafka’s legacy and importance today.