Aleksandra Majak is currently working on her DPhil in English and Slavonic literature of the twentieth and twentieth-first century. In her project she looks on how the influx of Central Eastern European poetry in translation has galvanized a new, more ‘direct’ mode of poetic expression in the Anglo-American lyric of late modernism. In this post she shares some thoughts on the work of the Polish author Olga Tokarczuk.

Photography: Łukasz Giza

‘Literature is built on tenderness toward any being other than ourselves,’ said Olga Tokarczuk in a deep, calm voice as she addressed the audience during her Nobel acceptance speech. In 2018, the Swedish academy honored her work for ‘a narrative imagination that with encyclopedic passion represents the crossing of boundaries as a form of life’. That – after Henryk Sienkiewicz, Wladyslaw Reymont, Czeslaw Milosz, and Wislawa Szymborska – made Tokarczuk the fifth Polish author to receive Nobel Prize in literature, and quite possibly the coolest one.

Tokarczuk is a feminist, activist and ethical vegetarian. Still, the most intriguing thing about this author is the way her at once intricate and disturbing books encourage readers to consider the boundaries between the real and the imagined; how, perhaps somewhere on the verge of both, we live in the world of stories yet untold. Indeed, she believes that ‘a thing that happens and is not told ceases to exist and perishes’. Much of her work muses on an ostensibly simple but ultimately rather complex question: why does storytelling matter?

Since her 1993 debut, The Journey of the Book-People, Tokarczuk’s works have explored stories of borderlands; often occurring at the intersections of languages, flowing between literary genres, and taking place botheverywhere and nowhere at once. Early responses to Tokarczuk’s work often focused on its peripheral status vis-a-vis more mainstream tendencies within Polish mid-1990s fiction, until her Primeval and Other Times (1996) – in which a fictitious village evolves into a microcosm of turbulent twentieth-century history and the lives of its eccentric characters intertwine – became her first widely appreciated novel.

Written in Polish, her books have been translated into over 37 languages, each translation offering a subtly new interpretation of the original. Here, meaning is not – as Robert Frost’s oft-quoted line asserts – ‘lost’ in translation. Instead, it is through translation that literature otherwise ‘foreign’ to some audiences comes to matter. Antonia Lloyd-Jones, an alumna of MML at Oxford and now an award-winning translator of Polish literature into English (including Tokarczuk’s novels), sees a rising interest in contemporary literature in translation but also hopes to see more lost or forgotten classics revived: ‘postwar Polish literature is full of neglected gems.’

So what exactly do critics – most of whom read Tokarczuk in languages other than Polish – have in mind when they esteem the writer for her ‘narrative imagination’ and ‘crossing the boundaries as a form of life’? Part of the answer has to do with the writer’s fascination with the possibilities of telling the same story in multiple ways. Her most complex novels are narrated with unusual ease but in purposefully fragmentary threads – told by unreliable or eccentric characters, or emerging in moments of narrative breaks and silences.

In fact, the author’s keenness for decentralised, maze-like, and box-within-a-box plotlines took is rooted in her interest in psychology, which she went on to study at the University of Warsaw. The novelist once told The Guardian that reading Freud in her youth was her first step towards becoming a writer. Exploring his works on psychoanalysis brought her to the realisation that there are countless ways to interpret our experience – that storytelling, akin to the human psyche, is made up of constellatory rather than linear structures. This excerpt from the English translation of her Nobel lecture captures her desire to challenge narrative linearity (this is at 48:08-50:09 of the online recording of the lecture):

I keep wondering if these days it’s possible to find the foundations of a new story that’s universal, comprehensive, all-inclusive, rooted in nature, full of contexts and at the same time understandable.

Could there be a story that would go beyond the uncommunicative prison of one’s own self, revealing a greater range of reality and showing the mutual connections? That would be able to keep its distance from the well-trodden, obvious and unoriginal center point of commonly shared opinions, and manage to look at things ex-centrically, away from the center?

I am pleased that literature has miraculously preserved its right to all sorts of eccentricities, phantasmagoria, provocation, parody and lunacy. I dream of high viewing points and wide perspectives, where the context goes far beyond what we might have expected. […]

I also dream of a new kind of narrator―a “fourth-person” one, who is not merely a grammatical construct of course, but who manages to encompass the perspective of each of the characters, as well as having the capacity to step beyond the horizon of each of them, who sees more and has a wider view, and who is able to ignore time.

In all its contradictions, the concept of ‘a fourth-person narrator’ is both odd and fascinating. It combines as well as transgresses the well-known forms of narration that we first got to know in school: first or third person narrator; omniscient or limited perspective; direct address or the detached observer. Here the dream for ‘a fourth-person’ narrator, imagined as a tender and curious observer, is not only about the actual narrator but about the dream itself. Its potency, rhetoric, and creative power is able to transcend all the boundaries of traditional narrative. And if the project is intentionally left unfinished, why do you think that might be?

Her polyphonic vision of narration is also important if we consider the political situation of contemporary Poland. In this climate, literature has had a long-standing patriotic obligation towards promoting a monolithic idea of the country and its culture, which – as the noted historian Norman Davies, who works on Central Eastern Europe, has remarked – allows ‘myth to flourish’. Many of these myths have left their mark and much of the Anglo-American accounts of Poland became homogeneous in responding to this.

When the popularity of translation increased rapidly in the mid 1960s, commentaries promoted a naive belief that East Central European literature might be characterised by a few political clichés, prizing its universal aesthetics, and offering the reader an interpretation typically full of loose references to turbulent history or the poetry of witness or survival. It would be tempting though ultimately trite to look on the phosphorescent structures of Tokarczuk’s plots as a counter-balance to the daily reality of a country now overshadowed (and gradually damaged) by the politics of the ruling homophobic Law and Justice (PIS) party.

Tokarczuk’s polyphonic narration resounds ever more meaningfully in the growing popularity of autobiographical writing, particularly the type of one-season celebrity-authored work which has little to offer beyond self-promotion. One of Tokarczuk’s concerns about today’s printing market is the dominance of tales that ‘narrowly orbit the self of a teller who more or less directly just writes about herself and through herself’, thus creating an paradoxical and alienating opposition between the ‘I’ and reality. For Tokarczuk, this presents yet another potentially fruitful opportunity for her to cross the boundary.

Still, if reading Tokarczuk is an exercise in boundary-crossing, it is not without a certain paradox, for to cross the boundaries is to admit that they do exist. The author references this contradiction in a scene from her untranslated book Final Stories (2015), where one of the characters tells the story of an undefined borderland moved during the night to some entirely different place, leaving the people ‘on the wrong side’; as the speaker adds with irony: ‘as humans cannot live without borders, we set off to find one’.

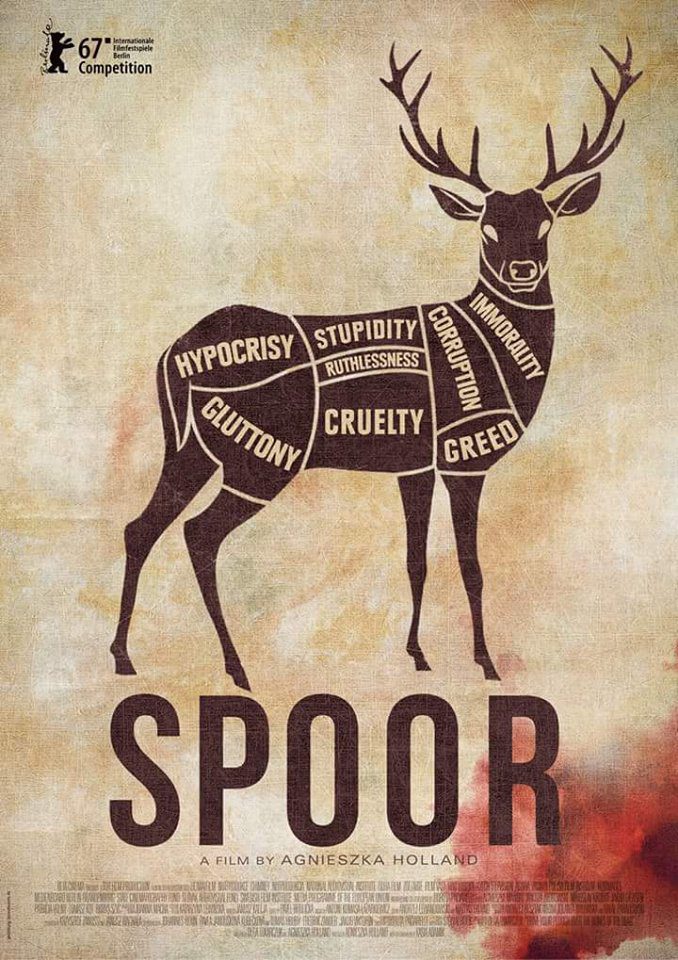

Other than readily available online resources, such as the full version of her Nobel acceptance speech, for a first read of Tokarczuk’s somewhat challenging work I would recommended Drive Your Plow Over The Bones of a Dead in the translation by Antonia Lloyd-Jones. This riveting novel toys with the genre of crime-fiction in its witty but dark quest to solve a mystery troubling the local community. Comparing the narrative to its film adaptation Spoor (2017) directed by Agnieszka Holland might spark a fruitful debate, especially in considering how the atmosphere and humour of the novel is translated into the visual language.

by Aleksandra Majak