Back in February we brought you news of an exciting translation competition being run by the Creative Multilingualism Programme, in connection with the exhibition at the Bodleian Library on ‘Babel: Adventures in Translation’. We are now pleased to share the winners of this competition.

Magical Translation

The task was to create a modern version of Cinderella in any language with an English prose translation. We received some fantastic entries in this category which played cleverly with the Cinderella story, adding twenty-first-century twists like Cinderella losing her luggage tag instead of a slipper, or being tracked down by the prince using social media. The best of these stories engaged with the question of Cinderella’s identity, manipulating the traditional tale to reflect on issues like Cinderella’s sexuality, her race, the prince’s gender identity, or the role of feminism in fairytales.

The overall winner of this task was fifteen-year-old Alice, whose version of the story, written in Spanish, sees Cinderella transported to the streets of Buenos Aires and dreaming of a football career…

En las calles sucias de La Boca, Buenos Aires, Cinderella Muños trabajó incansablemente por su madrastra y sus dos hermanastras. “Trabaja duro y agradece” le dijeron a ella. A Cinderella siempre le encantó el fútbol y soñaba jugar para su equipo local: Boca Juniors, a pesar de siendo una niña. Sus padres tenían boletos de temporada, sin embargo, tristemente cuando murieron, los boletos fueron entregados a su madrastra. Cinderella tenía prohibida ver algún partidos. A pesar de eso, su amor por fútbol nunca se detuvo y en las calles de La Boca practicaría todas las noches. Cinderella fue devastada perderse la victoria de Boca Juniors en las finales de la Primera División contra Plate River. Mientras se sentaba tristemente en las escaleras, vio un sobre de oro que contenía tres entradas para una fiesta para celebrar la victoria. Su madrastra se las arrebató como quería que sus hijas conocer el famoso futbolista: Jorman Campuzano. se vistieron de azul y amarillo (los colores del equipo) y salieron, dejando a Cinderella completamente sola. Estaba muy triste mientras ella pateó su fútbol por las calles oscuras. En la fiesta, Jorman miró fuera la ventana y él estaba asombrado por la curiosa figura quien dominó la hábil patada del arco iris. Se impresionó aún más y pronto se unió. Cuando el reloj golpeó a las doce, ella escapó, dejando atrás su fútbol, con el nombre: Cinderella Muños. Poco después, Jorman la encontró y la invitó ella probar para el equipo, y desde ese día, ella nunca más tuvó que ver a su madrastra o hermanastras.

In the dirty streets of La Boca, Buenos Aires, Cinderella Muños worked tirelessely for her stepmother and two spoilt stepsisters. “Work hard and be grateful” she was told. Cinderella always loved football and dreamed of playing for the local team, Boca Juniors, despite being a girl. Her parents owned season tickets however, sadly when they died, these tickets passed to her step mother Cinderella was forbidden to watch any matches. Despite this, her love for football never ceased and in the streets of La Boca she would practice nightly. Cinderella was devastated to miss Boca Juniors’s victory in the Primera division finals against Plate River. While she sat sadly on the steps she noticed a golden envelope which contained three tickets to a party to celebrate the victory. Her step mother snatched them away as she wanted her daughters to meet the handsome footballer Jorman Campuzano. They dressed in blue and yellow (the team colours) and set off, leaving Cinderella all alone. She felt very lonely as she kicked her football along the dark streets. Up at the party, Jorman looked out the window and was amazed by the curious figure who mastered the skilful rainbow kick. He became ever more impressed and soon joined in. As the clock struck twelve she ran off leaving behind her football with the name: Cinderella Muños. Shortly after, he found her and invited her to trial for the team, and from then on never had to see her step mother or sisters again.

To see other winners and highly commended entries in this task, check out the page on the Creative Multilingualism website here.

Fabulous Translation

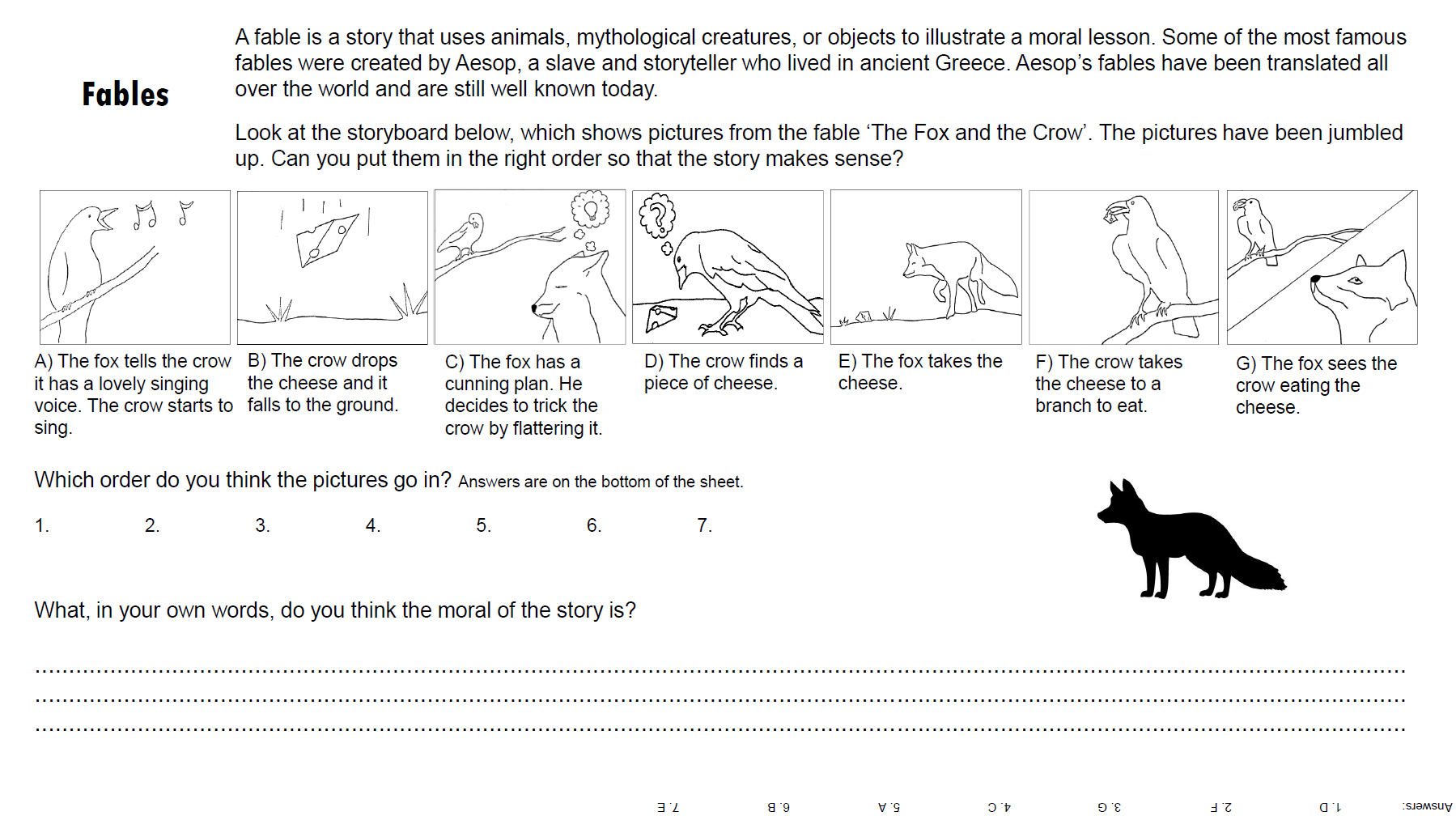

The task was to create a fable – an animal story with a moral – in any language with an English prose translation. The fables we received were wide-ranging and hugely imaginative. Stories were written in French, German, Italian, Irish (Gaelic), Korean, Spanish, and Yoruba. We read tales about foolhardy frogs leaping on the heads of crocodiles, a jealous rat envying a peacock’s beauty, dogs looking for love, a dolphin betraying its mother’s trust, and a crow going head-to-head with an eagle. The strongest stories in this task were filled with vivid imagery, linguistic courage, and showed a willingness to engage thoughtfully with the structure and purpose of the fable genre, often illustrating complex morals with subtle simplicity.

The overall winner of this task was thirteen-year-old Clémence, who wrote a poignant and visually striking fable in French about the consequences of not preparing for winter.

‘Un hiver long et froid’

Un jeune Cacatoès a huppe rouge se positionna sur la branche la plus haute du grand chêne. Son plumage était d’un des plus majestueux et sa huppe d’un couleur cramoisi. Son regard lumineux faisait scintiller la foret pleine de végétation. Ou, c’est ce qu’il croyait. Ses parents cacatoès pépiait sans cesse de leurs fils précieux.

En bas, dans l’un des trous les plus sombre vivait une petite famille d’écureuil roux. Leur fourrure était toute douce, comme les nuages et portait un point d’interrogation tout doux pour une queue. Ils étaient silencieux et rapides, travaillait dur et s’organiser. Leurs petites moustaches repairaient le vent tourner au nord, symbolisant l’arrivée de l’hiver, un hiver sombre et froid.

Le plus jeune écureuil regarda le haut du grand chêne avec intérêt. Il n’avait jamais récupéré les noix là-haut, celles qui était les plus juteuse. L’idée lui monta à la tête. Quel mal ferait t’il d’essayer. En plus l’hiver s’approcha de plus en plus, il fallait faire des récoltes.

‘Mais que fais-tu là-haut petit écureuil.’ Lui chanta le cacatoès.

‘Et toi, tu n’as pas fait tes provisions’ réponds l’écureuil.

‘Moi, je suis trop beau et intelligent pour telles taches ! L’hiver viendra quand ça me chantera !’

‘Toi tu te crois sorti de la cuisse de Jupiter mon pauvre. La neige et le vent te changera les idées.’

L’hiver arriva sans même dire un autre mot. La famille écureuil se tenait au chaud autour de la grande réserve lorsque la famille cacatoès, on ne les distinguer presque pas avec la neige nacrée.

A young red crested cockatoo positioned himself on the highest branch of the large oak. His plumage was one of the most majestic and a crimson colour. His glowing eyes made the forest full of vegetation glitter. Or, that’s what he believed. His cockatoo parents constantly chirped about their precious sons.

At the bottom, in a dark hole, lived a small family of red squirrels. Their chestnut fur was soft, like clouds, and had a question mark for a tail. They were silent and fast, hard working and organised. Their little moustaches sensed the north wind coming, symbolising the arrival of winter, a dark and cold winter.

The youngest squirrel looked up the large oak with interest. He never collected the nuts up there, the ones that were the juiciest. The idea rose to his head. What harm would it do to try. In addition the winter was coming and provisions where needed.

“But what are you doing up there little squirrel?” Sang the cockatoo to him.

“And you, you have not yet made your provisions” answered the squirrel.

‘I am too handsome and intelligent for such jobs! Winter will come when I want it too! ‘

‘You believe yourself to have come out of the thigh of Jupiter my poor. Snow and wind change your ideas. ‘

Winter arrived without even saying another word. The squirrel family kept warm around the great reserve unlike the cockatoo’s family, we hardly distinguish them against the pearly snow.

You can read more of the highly commended fables here. Well done to all the winners and many thanks to everyone who took part! Some of the winning stories will be on display this Saturday, 15 June, at the Oxford Translation Day. This is a day full of translation events, which are free to attend. You can find the full programme here.

If you are near Oxford and your thirst for translation has not yet been quenched, do consider going along – and be sure to check out the winning Babel stories while you’re there.