In our final blog post before Christmas, first year French & Philosophy student at St John’s College, Laurence, tells us all about his first term at Oxford – settling in, making friends, and exploring new literature… over to you, Laurence!

I have finished my first term studying Philosophy and French at St John’s College, and what a rollercoaster it has been! Freshers’ week, matriculation [1], my first tutorial [2]… and all while making new friends and starting to feel at home in Oxford. I initially wanted to study Law but decided that I first wanted to explore French literature and culture, as it had been my favourite subject during A levels. It is not a decision that I have come to regret! I would recommend French at Oxford to anyone with a passion for languages and literature.

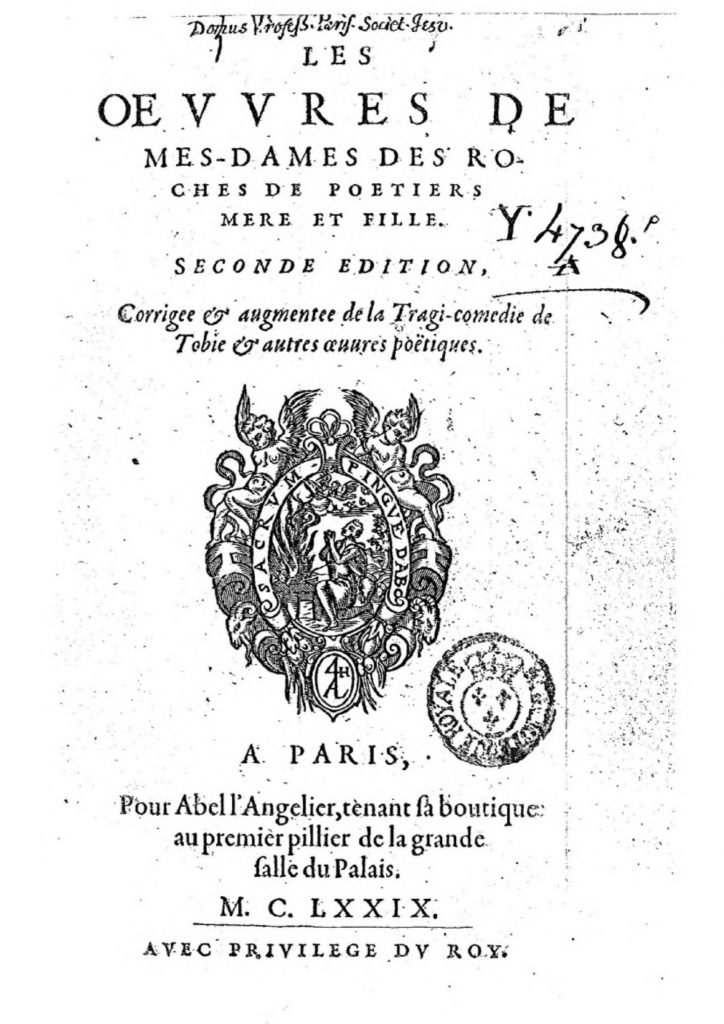

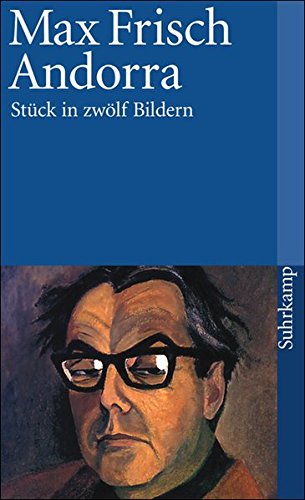

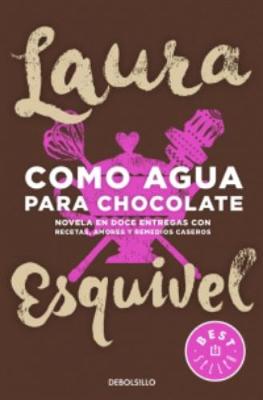

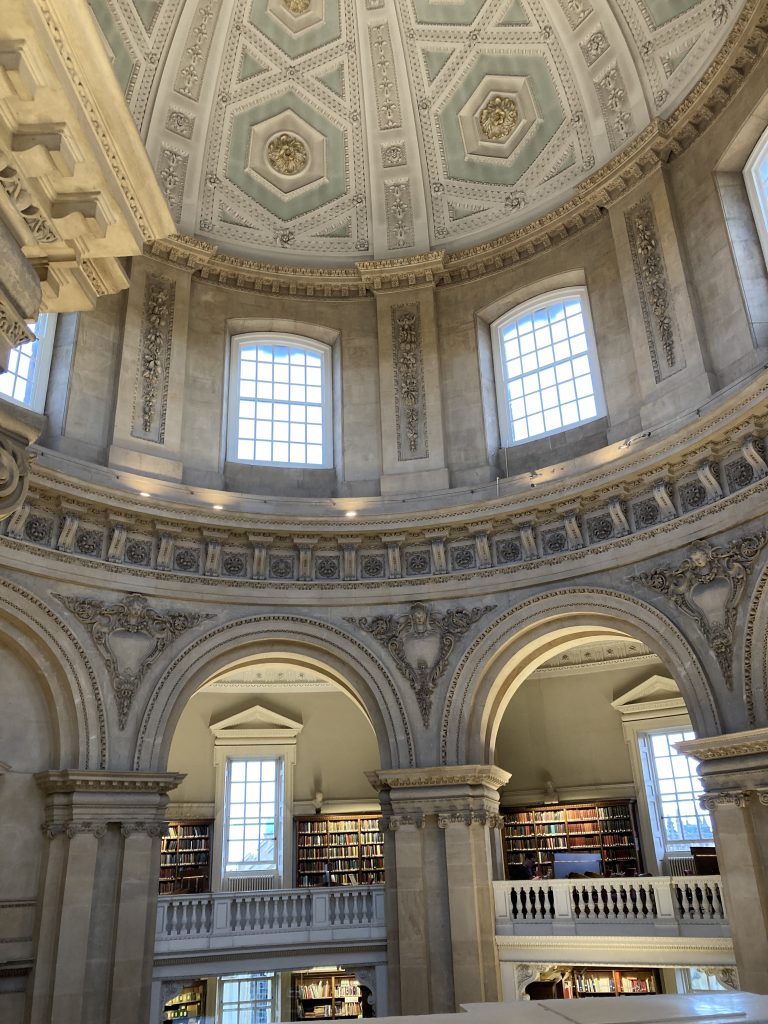

The French course at Oxford is varied and engaging, with something for everyone. The first year syllabus is perfect for helping students get a sense of what they might like to pursue in future years – in the space of eight weeks I studied French essays, tragedies, and poetry. These included Michel de Montaigne’s Des Cannibales (c. 1580) which sheds light on French attitudes to South American tribes, raising fascinating questions of religious politics, Gallic identity, and colonialism’s fallacious distinction between savage and civilised cultures. Montaigne also pioneered the form of the ‘essay’ itself and his later revisions and editions to the initial text demonstrate his attempts to grapple with complex subject matters. We touched on all these points and more in our classes and tutorials, which are supplemented by lectures in the beautiful Taylor Institution Library.

Another benefit of the course is the variety of subjects that can be combined with French: whilst I study philosophy, I have friends studying French and English, Arabic, German, and linguistics, to name a few. I think Philosophy and French is a great combination… in later years I will have the opportunity to read the philosophical works of Descartes, Sartre, Pascal, and Merleau-Ponty in their original French, as well as studying the philosophy of language.

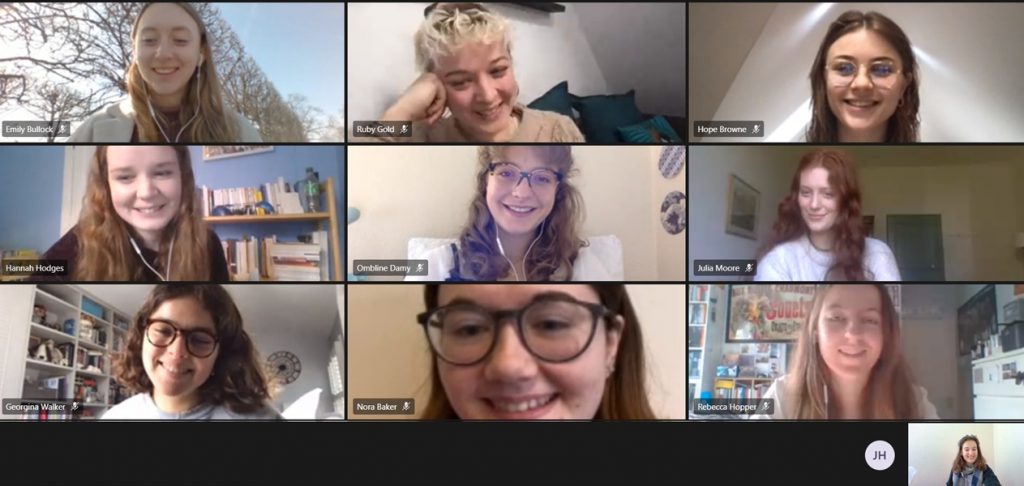

On an average day in my week, I might wake up early and go to the Radcliffe Camera for at least an hour of work as it is my favourite study spot. After a couple of lectures or a tutorial and then some lunch, I might have a grammar or conversation class. I particularly enjoy these because I love speaking in French, and there is no better place to practise than with the patient, friendly native speakers that are employed at St John’s to help us improve. We have discussed topics as varied as the Bouquinistes (book sellers on the banks of the Seine in Paris) and the life of Louis XIV, the ‘Sun King’, through presentations, debates, and games. After dinner, my class might work on a translation together or do some reading in the college library. The collaborative element of language learning is really encouraged in the Oxford environment – tutors want us to test each other on vocab and speak French among ourselves wherever possible. You might even find a native French speaker in your college – I often test my speaking skills with my Canadian friend!

Finally, life at Oxford is not all about work. I enjoyed a languages ‘initiation’ party in college where second year language students encouraged us to dress up as figures from our personal statements. I came as Socrates, and one friend of mine donned his long, black wig as Madame Bovary! In short, life as a language student at Oxford has so much to offer…

Thank you Laurence for that excellent insight!

After a short break over Christmas, we’ll be back with more blog posts in the new year. For now, we wish you a restful and joyous festive period with loved ones. Bonne fêtes à toutes et tous!

[1] An Oxford ceremony that marks a student’s induction as a member of the university.

[2] A teaching format of a tutor and 1-3 students.