Present-giving around the turn of the year involves traditions which vary from country to country. In different parts of the world, gifts are brought by Father Christmas, Saint Nicolas (more about this here) or the Three Wise Men (the Spanish ‘Reyes’ or Kings).

In Bergamo and some other parts of Northern Italy, Santa Lucia, a 4th-century martyr from Syracuse in Sicily, is the one who distributes treats to children. With a name based on the Latin root for light (Lux), Santa Lucia is celebrated close to the shortest days of the year with candles (like in parts of Scandinavia) and gifts which bring good cheer in times of darkness. An (incorrect) Italian saying holds that ‘Il giorno di Santa Lucia è il più corto che ci sia’, Santa Lucia’s day is the shortest one there is—the longest night actually falls on the winter solstice. Santa Lucia (or St Lucy) is the patron saint of the blind and of opticians, and she is often represented holding a plate or a staff on which sit a pair of eyes as an allusion to an episode in her life. The Italians value the figurative meaning of light and view Santa Lucia as a figure representing a form of wisdom and clear-sightedness.

The reason for Santa Lucia’s importance in Bergamo is to be found in the presence of her relics in Venice—the large church of Santa Lucia, not far from the train station which bears her name, was built to house them. Bergamo, which is in Lombardy, was (until the end of the eighteenth century) a part of the territories of the republic of Venice and the lion of St Mark is visible on town gates, fountains and other constructions throughout the town.

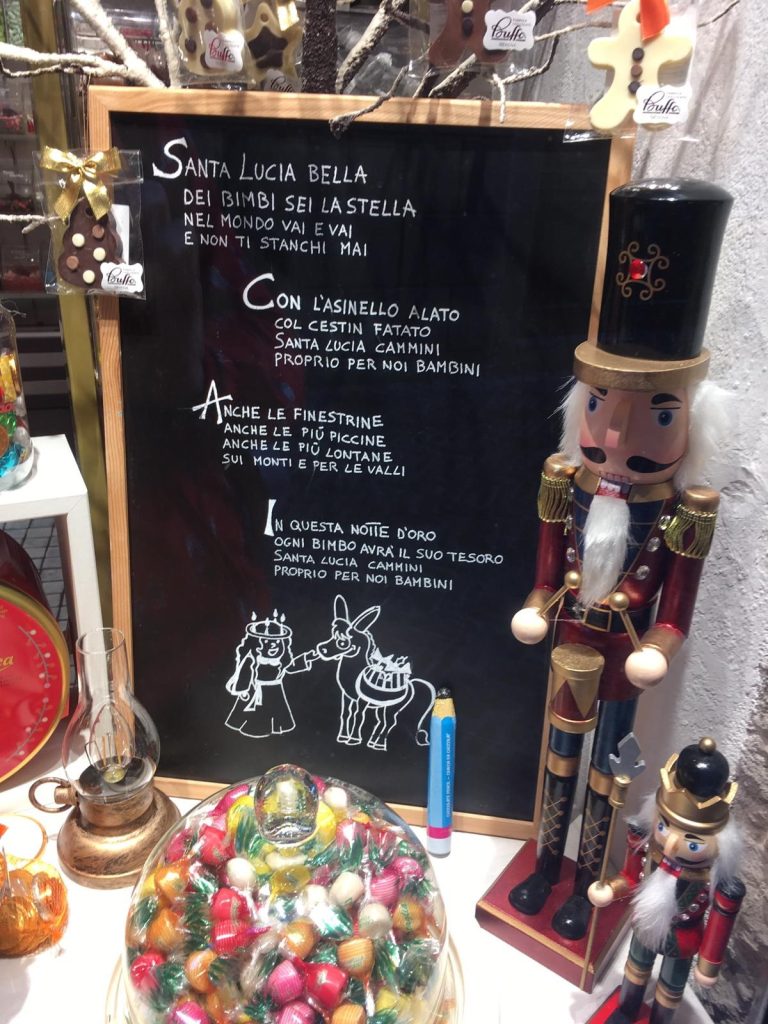

Whilst Santa Claus has his reindeer, Santa Lucia is said to be accompanied by a donkey, her asino or asinello. He is sometimes described as alato or winged to help him fly from house to house on his mission to deliver presents—at the top of the page you can see a picture of the saint and the donkey on the blackboard showing a festive poem which was in the window of a confectioner’s in Bergamo. Since the early 20th century, children in the city have taken to writing letters to Santa Lucia to give her an idea of what they would like and, sometimes, to assure her that they have spent the year being good. The letters, known as letterine (for little letters or lettere) are taken to a small church and set in colourful piles in front of the saint’s statue.

When I visited the church, I was struck by the variety of the letterine and the canny approach some of the authors had taken. To guarantee that the presents will go to the right place, the children make sure their names are on their messages.

Stefano wrote his in large capitals. A parent had possibly added on a red envelope that another letter was from la piccola Amelia—little Amelia. One child hedged her bets and addressed her requests to both Santa Lucia and Babbo Natale—Father Christmas!

A girl called Gaia wrote Cara Santa Lucia mi piacerebbe ricevere questi regali or Dear Santa Lucia, it would please me to receive these gifts and then stuck five pictures out of a catalogue showing what she hoped she would get. Next to the photograph of pink headphones she added Senza filo, literally without thread or wire, i.e. cordless, to make sure the right pair was delivered.

Until December 12, children drop in to the church, clutching their letters and dropping them on the top of the growing piles of missives. That evening, at home, they will prepare snacks for the saint and her donkey—she gets biscotti and milk, he gets carrots, water and sometimes hay. They then go to bed and are instructed to sleep: Santa Lucia is said to throw ashes into the eyes of naughty girls and boys. The next morning, on waking up, if they have been good, they will find lots of sweet treats including monete di cioccolato—chocolate coins—and, possibly, some of the gifts for which they had asked.

Written by Catriona Seth, Marshal Foch Professor of French Literature

All Souls College, Oxford