Posted By Rowan Lyster, a third year at Somerville College, reading French and Linguistics, and is currently on her year abroad in Montpellier, France. This is an extract from rowanlyster.blogspot.fr

I’ve decided it’s time that the secret competitiveness of being-on-a-year-abroad was made official, and have created the Year Abroad Game. Rewards are measured in smug-points; any inconsistencies in the rules are down to artistic licence (and definitely not the fact I couldn’t be bothered to make up a proper scoring system).

START: You find yourself trapped in a foreign land where nobody has heard of Doctor Who. Will you survive?

Gain 5 points for each cool attraction you discover in your new hometown.

Such as the ice rink, which has a disco section complete with a light tunnel and hills. In classic French style, this is completely dark, and full of terrifyingly reckless locals. Great fun, despite frequent near-death experiences.

Gain 2 points (and a few pounds) every time you sample a local foodstuff

such as crêpes, of which I’ve eaten a shocking number since discovering the heaven-in-a-pancake that is Nutella with Speculoos-spread.

Gain 10 points if you wring a smile out of one of the bitter and twisted administrators you’ll no doubt encounter.

Such as the receptionist of my accommodation, who regularly tells off residents for the heinous crime of asking for our post. After a determined campaign of sickly sweet bonjour’s, I miraculously got a friendly smile back.

Lose 15 points and go back 3 spaces if you let out a snarky comment to one of the bitter and twisted administrators who’ll no doubt be pointlessly rude to you.

Believe me, the former is ultimately a better way of getting things done.

Gain 30 points if you get a non-disastrous haircut during your time abroad.

I managed this the other day, despite an alarming lack of French hairdressing vocabulary. Aside from nearly accepting an unwanted fringe, it went surprisingly well!

Gain 20 points if you go on a spontaneous trip with no particular destination in mind.

We accidentally did this after attempting to go to Nîmes by bus (it turns out there is no bus to Nîmes, despite the confident assertions of 6-8 locals who sent us on a frankly impressive wild goose chase). After giving up on Nîmes, we hopped on a bus and ended up in Pézenas, a gorgeous town an hour or so away.

|

|

Pézenas

|

Gain 15 points for each new town you visit.

The Nîmes story has a happy ending; we finally made it there (by train) the other day!

|

|

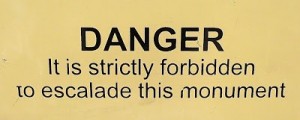

We saw this gem…

|

|

|

…and this badass.

|

Gain A MILLION POINTS if you ever manage to actually receive CAF (the French housing allowance).

I was lulled into a false sense of security by a letter saying I’d been approved for this, but apparently that’s just a hilarious prank they like to play before asking you for every document you’ve ever heard of and a lot that you haven’t. On the plus side, there’s free money available to anyone willing to undergo the seven labours of Hercules.

Lose 1 point every time you accidentally insert snippets of English e.g. ‘yknow,’ and ‘like,’ into your target language.

This is particularly embarrassing in official meetings.

Gain 10 points for each new hobby you take up.

I’ve joined a walking group. Yes, I have become my parents… It’s actually a great way of exploring, as the people with cars drive everyone to somewhere cool.

Gain 15 points per nationality for all the international students you manage to befriend.

So far I’ve met people from Germany, Spain, Italy, Algeria, America, Switzerland, Poland, Brazil and Hungary.

Gain 30 points if you do something ridiculously brave that you’d never do at home.

I went with a German friend to a café that had libre-service instruments, and eventually decided to go for the plunge and play the piano in public. Nobody booed, although hell may have frozen over.

Wild card: OH MY GOD ANYTHING COULD HAPPEN if you completely change your plans for the year.

By ‘completely’ I mean ‘quite a lot’ – I’m moving house at Christmas and have replaced a lot of my study-time with volunteering-time, which conveniently involves interacting with Actual French People.

Gain 100 points if you get mistaken for a French person by another foreigner.

This has happened to me a few times, albeit briefly. I’m also often asked if I’m German, due to my Nordic good looks (I like to think).

And if you get mistaken for a French person by an Actual French Person

Go home, you have won.

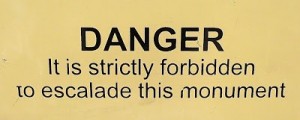

|

|

Here’s a bonus picture of the French doing what they do best: taking extremely strange things rather seriously. This man was darting about and pointing at people, occasionally shouting “ACHEVÉ!” all filmed by solemn people in white coats. Here’s a bonus picture of the French doing what they do best: taking extremely strange things rather seriously. This man was darting about and pointing at people, occasionally shouting “ACHEVÉ!” all filmed by solemn people in white coats.

|