posted by Simon Kemp

Last week we saw the slippery way in which Meursault tells his story from different points along the way, without drawing attention to the fact that he’s doing it.

I left you with the opening lines of the story, which contain the first of Meursault’s time-slips, with an invitation to look at the verb tenses and catch him in the act.

Here’s the passage again, with all the verbs in different colours used to highlight the présent, futur, passé composé, imparfait and futur antérieur (‘will have done’) tenses:

Aujourd’hui, maman est morte. Ou peut-être hier, je ne sais pas. J’ai reçu un télégramme de l’asile: “Mère décédée. Enterrement demain. Sentiments distingués.” Cela ne veut rien dire. C’était peut-être hier.

L’asile de vieillards est à Marengo, à quatre-vingts kilomètres d’Alger. Je prendrai l’autobus à deux heures et j’arriverai dans l’après-midi. Ainsi, je pourrai veiller et je rentrerai demain soir. J’ai demandé deux jours de congé à mon patron et il ne pouvait pas me les refuser avec une excuse pareille. […] Pour le moment, c’est un peu comme si maman n’était pas morte. Après l’enterrement, au contraire, ce sera une affaire classée et tout aura revêtu une allure plus officielle.

J’ai pris l’autobus à deux heures. Il faisait très chaud.

You can see first of all just how complex it all is when you use tenses to work out how everything relates to everything else in time. In the first two paragraphs, the present tense is used to set the scene with facts (L’asile de vieillards est à Marengo) and to tell us Meursault’s current situation (he doesn’t know when his mother died, the line in the telegram doesn’t mean much, it is a bit like she’s not dead). From that present tense anchoring us in now, we head back to events in the past: his mother died, he received a telegram about it, he asked his boss for some leave. With the imperfect we get a situation in the past (his boss wasn’t able to refuse), and a hypothetical alternative present (it feels as if she weren’t dead). We look ahead to a future in which Meursault will get the bus, will arrive at the old people’s home, will watch over the body, will come back home, and the whole business will be over and done with. And finally Meursault imagines looking back to the past from the future, from which point everything will have taken on a much more official air.

So, as you see, the opening lines establish a knot of past and future events around Meursault’s now, from which he’s telling his story, a point after getting the news of his mother’s death and speaking to his boss, but before heading off to the funeral. Straight away, though, when we get to the third paragraph, this now has shifted. The action that Meursault got on the bus and the situation that it was hot are now in past tenses, which means the events are in Meursault’s past, and his storytelling now must have shifted some way into the future.

There are other odd little references to the storytelling now in the book. In Chapter Four, as Meursault is telling us about the day Raymond’s attack on his girlfriend brought a policeman to the flat, he starts by saying what happened ‘ce matin’ suggesting that he’s narrating the chapter from later the same day. And the last chapter of the novel seems to pull a similar trick to the first: the opening lines are narrated from a now before the prison chaplain has come into Meursault’s cell, and then at some point we jump forward, and the chaplain’s visit is told in the past tense. That means there are at least five different points from which the story is told, and probably more — perhaps every chapter is told from a different moment in time.

So what’s the point of doing this?

One important effect is that it makes the novel immediate. Meursault is always telling his story from a point close to the action, either in the heart of events or shortly afterwards when they’re fresh in his mind. This makes the novel much more vivid, and allows us to share Meursault’s experience much more closely, than we would if he were telling us the story retrospectively from a point after it was all over.

Secondly, a related effect is that the story being told feels raw. Because he’s telling us the story more or less as it happens, he hasn’t had much time to process or analyse it. That means he gives it to us straight, without having really thought deeply about what things mean, but also without trying to present things in a way that might put him in a good light. This makes the storytelling seem honest and sincere.

And lastly, the intermittent time of narrating means that Meursault has no hindsight. As he’s telling us about the funeral, he doesn’t know the terrible consequences that his trivial actions will have when they’re brought up at his trial as evidence of his heartless nature. As he agrees to write a letter for Raymond, he doesn’t know that he’s taking the first step along the road to his own conviction for murder. Camus’s philosophy of life, like that of his friend, Jean-Paul Sartre, emphasised the randomness of life. For them, life, unlike stories, was not heading for a particular conclusion and had no meaning or message to impart along the way. Camus’s way of telling his story as it goes along is part of his attempt to capture a vivid sense of life as unplanned and unpredictable.

As a guy who takes life as it comes, going with the flow without too much thought or effort, Meursault doesn’t seem the type to keep a diary. Nor is he the sort of person who’d be writing an autobiography for publication, or even someone likely to recount his story to friends over a drink. This might be why the novel keeps its unusual storytelling in the background. We’re meant to feel that the narration is close to the action, but perhaps not enquire too closely as to how, why, and to whom Meursault is telling his story.

posted by

posted by

![photo [8485]](http://bookshelf.mml.ox.ac.uk/wp-uploads/2016/01/photo-8485.jpg)

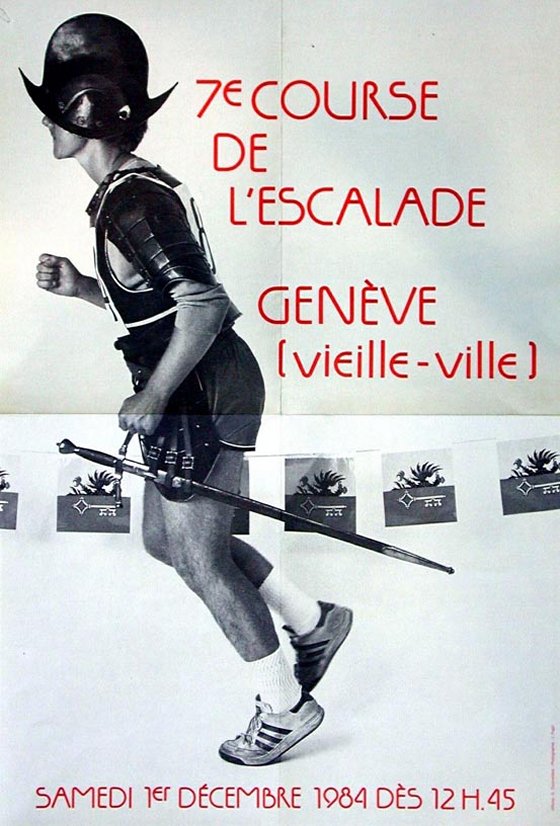

It is hugely popular and, made up in fact of several races according to the distance you want to run, your age etc. It happens in early December and is the largest event of its kind in Switzerland with tens of thousands of men, women and children taking part, some in fancy dress. Doubtless many of those who start when the whistle is blown and they hear

It is hugely popular and, made up in fact of several races according to the distance you want to run, your age etc. It happens in early December and is the largest event of its kind in Switzerland with tens of thousands of men, women and children taking part, some in fancy dress. Doubtless many of those who start when the whistle is blown and they hear