https://youtu.be/CXiQtJXTZSo

posted by Simon Kemp

It’s university admissions time again, and Oxford has been trying to take some of the mystery out of our interview process. As well as releasing the video above, the university has been asking its tutors to reveal the questions they ask interview candidates. The story has been widely reported in newspapers, as well as on the BBC website here.

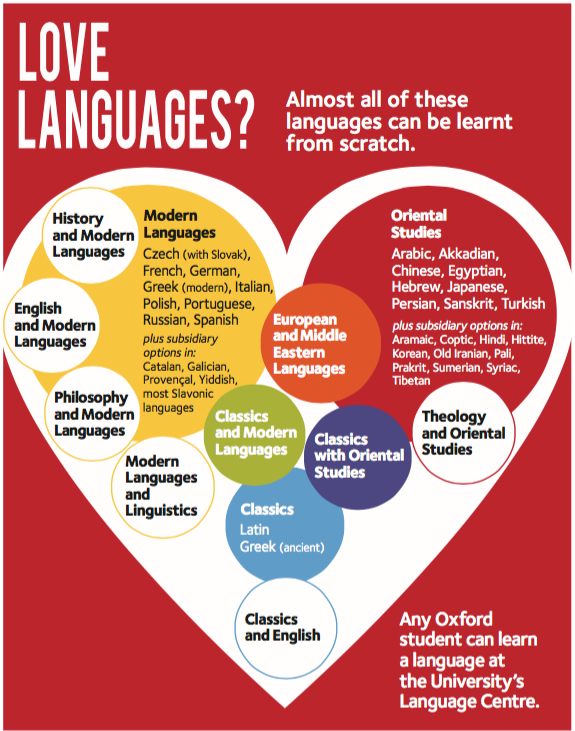

One of the questions was from an interview for a place on a degree involving French:

What makes a novel or play “political”?

This was a question for a French course. Interviewer Helen Swift, from St Hilda’s College, said:

“This is the sort of question that could emerge from a student’s personal statement, where, in speaking about their engagement with literature and culture of the language they want to study, they state a keen interest in works (such as a novel, play or film) that are “political”.

“We might start off by discussing the specific work that they cite (something that isn’t included in their A-level syllabus), so they have chance to start off on something concrete and familiar, asking, for instance, “in what ways?”, “why?”, “why might someone not enjoy it for the same reason?”.

“We’d then look to test the extent of their intellectual curiosity and capacities for critical engagement by broadening the questioning out to be more conceptually orientated and invite them to make comparisons between things that they’ve read/seen (in whatever language).

“So, in posing the overall question, ‘What makes this political?’ we’d want the candidate to start thinking about what one means in applying the label: what aspects of a work does it evoke? Is it a judgement about content or style? Could it be seen in and of itself a value judgement? How useful is it as a label?

“What if we said that all art is, in fact, political? What about cases where an author denies that their work is political, but critics assert that it is – is it purely a question of subjective interpretation?

“A strong candidate would show ready willingness and very good ability to engage and develop their ideas in conversation. It would be perfectly fine for someone to change their mind in the course of the discussion or come up with a thought that contradicted something they’d said before – we want people to think flexibly and be willing to consider different perspectives…

“Undoubtedly, the candidate would need to take a moment to think in the middle of all that – we expect that “ermmm”, “ah”, “oh”, “well” will feature in someone’s responses!”

There are further details about the Oxford interview on the university website here.

And you can explore lots more on the subject in the blog archives in the ‘Applying to Study Modern Languages’ category.