We’ve posted on here before about UNIQ, Oxford University’s flagship outreach programme. The UNIQ programme, which is for Year 12 students at UK state schools/ colleges, is a fantastic opportunity to immerse yourself in the Oxford environment, sample some of our teaching, and try out life as an Oxford student. The big news this year is that UNIQ has expanded and the University is now able to take double the amount of students for this programme than in previous years. So if you’re in your first year of further education and are thinking Oxford might be for you, send in your application to UNIQ by 28 January 2019. Read on to find out more or check out the UNIQ website….

What is UNIQ?

UNIQ is open to students studying in their first year of further education, who are based at UK state schools/colleges. Students make a single application between December and January and can be selected to participate in one of two activities: UNIQ Digital or UNIQ Spring and Summer.

UNIQ Spring and Summer gives you a taste of the Oxford undergraduate student experience. You will live in an Oxford college for a week, attend lectures and seminars in your chosen subject area, and receive expert advice on the Oxford application and interview process. The timetable also allows plenty of time for social activities; in the evenings you are free to tour the city, sample some of the University’s sports and cultural facilities, and let your hair down at the farewell party.

UNIQ Digital provides comprehensive information and guidance on the university admissions process, and aims to give you a realistic view of Oxford student life through videos, activities and quizzes. The platform offers a range of forums where you can discuss both academic and social topics. These forums are monitored by student ambassadors, who are always on hand to answer questions and offer support.

What does this look like for Modern Languages?

The in-person Modern Languages UNIQ courses have been slightly restructured during the UNIQ expansion. This year, we will be offering courses in French, German, and Spanish, with each of those courses also incorporating an introduction to a language from scratch (Italian, Portuguese, Russian, or German*). What this means is that you will apply for a course in French, German, or Spanish but you will effectively cover two languages during the summer school. The first two days of the course will be spent focussing on the language you study at A Level (or equivalent), including sessions to hone your language skills and knowledge of grammar, as well as lectures and seminars introducing you to an exciting array of topics in literature, culture, or linguistics, from the medieval period to the present day. During the final two days, meanwhile, you will be given the opportunity to study an unfamiliar language from scratch, learning some beginners’ grammar and new phrases, and exploring a new culture through its literature, film, or linguistics. The dates for the Modern Languages UNIQ courses are 14 – 18 July and 21 – 25 July.

* Participants will be allocated to a ‘new’ language by us. Those already studying German at school will not be allocated to German as a new language.

How do I apply?

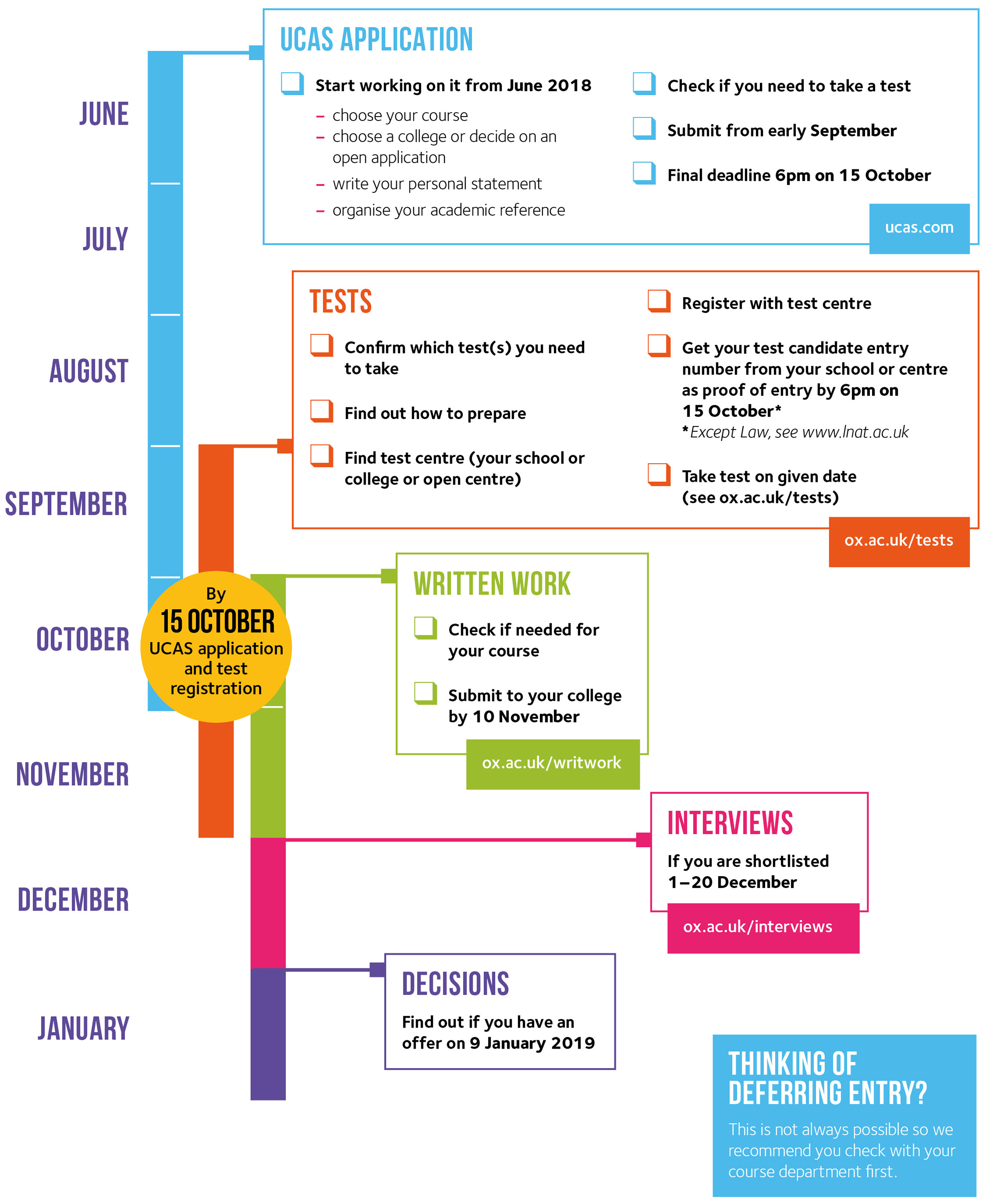

To be eligible for UNIQ you must be studying in your first year of further education at a UK state school or college and you must reside in the UK. For Modern Languages UNIQ courses, we would expect you to be studying the language for which you apply to A2 Level. Although we would generally expect you to have high GCSE grades, we are aware that, sometimes, circumstances arise which mean you do not perform to the best of your ability at GCSE. If this is the case, you should fill in the extenuating circumstances section of the application form. This doesn’t guarantee you a place on UNIQ, but when we look at the applications we will take this into account.

You should apply online through the UNIQ website. You will need:

- At least six GCSE/National 5 (or equivalent) qualifications, with a preference for 8-9/A-A* grades

- A short statement detailing interest in your chosen course

- School Information (Current UK state school/college and a past school)

- Your current A-level/Scottish Higher (or equivalent) courses

- Contact details of a current teaching referee

- Contact details of a parent/guardian referee

You will receive an email on the 25 February containing the result of your application.

Good Luck!