Ramani Chandramohan is studying for an MSt in Modern Languages at St Anne’s College, and is a long-standing cinephile. In this post she shares some of her favourite French films from her language-learning journey so far.

It’s a Sunday evening. You’re chilling in bed watching Netflix. And yet you’re also improving your French at the same time. How is this possible?!

Watching films via any streaming platform or with good old fashioned DVDs is a great way of immersing yourself in the language you are studying beyond grammar textbooks. Films showcase vocabulary, regional accents, culture, history and politics in ways that books alone cannot. Whilst it may be frustrating to not be able to understand what is happening initially or to rely on subtitles, you can eventually work your way up to changing the subtitles to your target language or maybe even turning them off altogether!

Here are some French films to get you started, although I have avoided some of the most well-known titles such as Les Intouchables, La Haine and Amélie.

Classics

These films are part of what is known as the Nouvelle Vague of the 1950s and 60s, a movement characterised by an emphasis on the artistic and the personal and elements such as improvised dialogue, jump cuts, location shooting and handheld cameras.

Jean Cocteau

- Orphée (1950) – this film, along with Le Sang du Poète (1930) and Le testament d’Orphée (1960), forms part of a trilogy that reimagines the ancient Greek myth of Orpheus and Eurydice in modern-day Paris.

La Belle et la Bête (1946) – a sumptuous retelling of the eighteenth-century fairytale originally written by Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont.

François Truffaut

- Les Quatre Cents Coups (1959) – this is the first in a series of five coming-of-age films about a rebellious young boy called Antoine Doinel which were based in part on Truffaut’s own childhood.

Jean-Luc Godard

- À bout du souffle (1960) follows the adventures of a petty thief and his American girlfriend in Paris.

- Bande à part (1964) – in this gangster film, two crooks who are fans of Hollywood B-movies commit a robbery with the help of an English student in Paris.

Agnès Varda

- Cléo de 5 à 7 (1962) – Varda was instrumental in the development of the Nouvelle Vague and she received the most votes in a poll conducted by the BBC of the greatest films made by female directors. This film focuses on Cléo’s wait for the results of a biopsy which could turn out to be a cancer diagnosis.

Marcel Pagnol

- La Fille du puisatier (2011) – set in Provence in the south of France, this film (based on Pagnol’s 1940 original) follows a father’s struggles as his daughter gets caught up with the son of a rich shopkeeper during the First World War. Other films based on Pagnol’s works include Jean de Florette (1986), Manon des Sources (1986), Marius (2013) and Fanny (2013). Pagnol championed authentic depictions of the south of France, overcoming prejudice against Southern accents in the French film industry.

- Bienvenue chez les Ch’tis (2008) – this cult classic reveals the hilarious fallout of a post office manager’s move from south to north and the clash of regional stereotypes. It made waves when it first came out, with TGV trains in the Nord-Pas-de-Calais region being decorated with film posters, and remains one of the highest-grossing films ever made in France.

Francophone

- La noire de…Sembène Ousmane was a famous Senegalese film director and writer; he is sometimes credited as the father of African film. La noire de… focuses on Diouana, who moves from Senegal to the south of France to work as a nanny for a rich French couple but is soon subject to racial discrimination.

- Un divan à Tunis (2019) – this film deals with a young psychotherapist called Selma who returns to Tunis after many years in Paris to set up her own practice, though it turns out to be far more challenging than she initially envisaged.

- Deux jours, une nuit (2014) – set in Belgium, this film stars Marion Cotillard and follows her character Sandra as she tries to convince her work colleagues to give up their bonuses to protect her job.

- Juste la fin du monde (2016) – Xavier Dolan is a young and prodigious film director from Montréal in Canada. This film tells the story of a terminally-ill writer who returns home after twelve years away to tell his family of his impending death.

Historical

- Au Revoir Les Enfants (2015) – a simple but affecting movie about two boys living in a boarding school in Nazi-occupied France during the Second World War.

- Le Bossu (1997) – this adventure film is an adaptation of Paul Féval’s 1858 historical novel Le Bossu and stars Daniel Auteuil as Lagardère, a swordsman who becomes friends with the Duke of Nevers. Auteuil is a famous French actor who has been in just about every French movie!

Romance

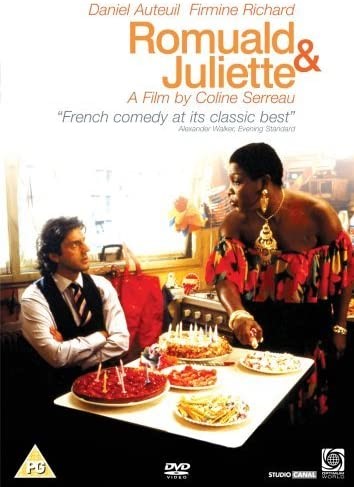

- Romuald & Juliette (1989) tells the story of a charming and somewhat unlikely romance between a cleaner working for a yoghurt company and the CEO.

- Populaire (2012) throws us into the world of typewriting contests in the 1950s in which love blossoms between a contestant, Rose, and her coach, Louis.

- Portrait de la jeune fille en feu (2019) tells the story of the relationship between an aristocratic lady and the female painter commissioned to paint her portrait.

- 120 BPM (2017) – winner of the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival, this film is set in 1980s France and focuses on the work of Act Up, an advocacy group that campaigns for legislation and research to alleviate the AIDS crisis.

Sci-fi

- La Planète Sauvage (1973) explores the tensions between two communities on the planet of Ygam: the Oms (small creatures who resemble humans) and the Draags, larger alien-like creatures who treat the Oms like animals and rule Ygam). This film is inspired by Stefan Wul’s 1973 novel Oms en série.

Feel-good

- Les Choristes (2004) – this was the first French film I ever saw and its charm, warmth and humour made me fall in love with the language. It follows music teacher Clément Mathieu’s attempts at setting up a choir out of a group of unruly school boys in a strict boarding school and, unsurprisingly, features a great soundtrack!

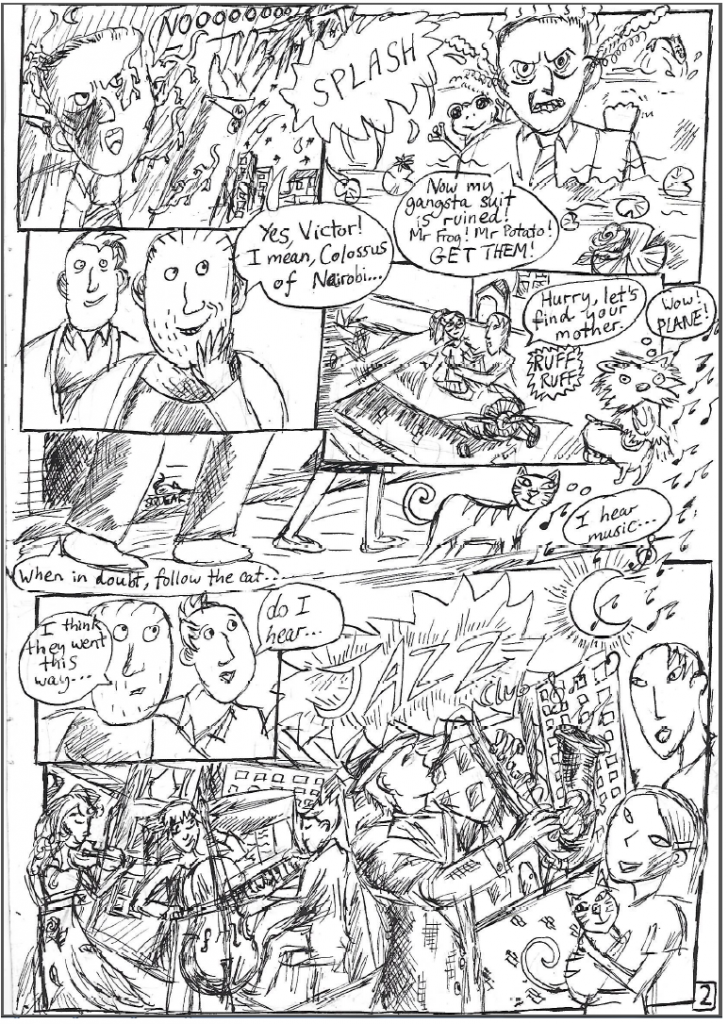

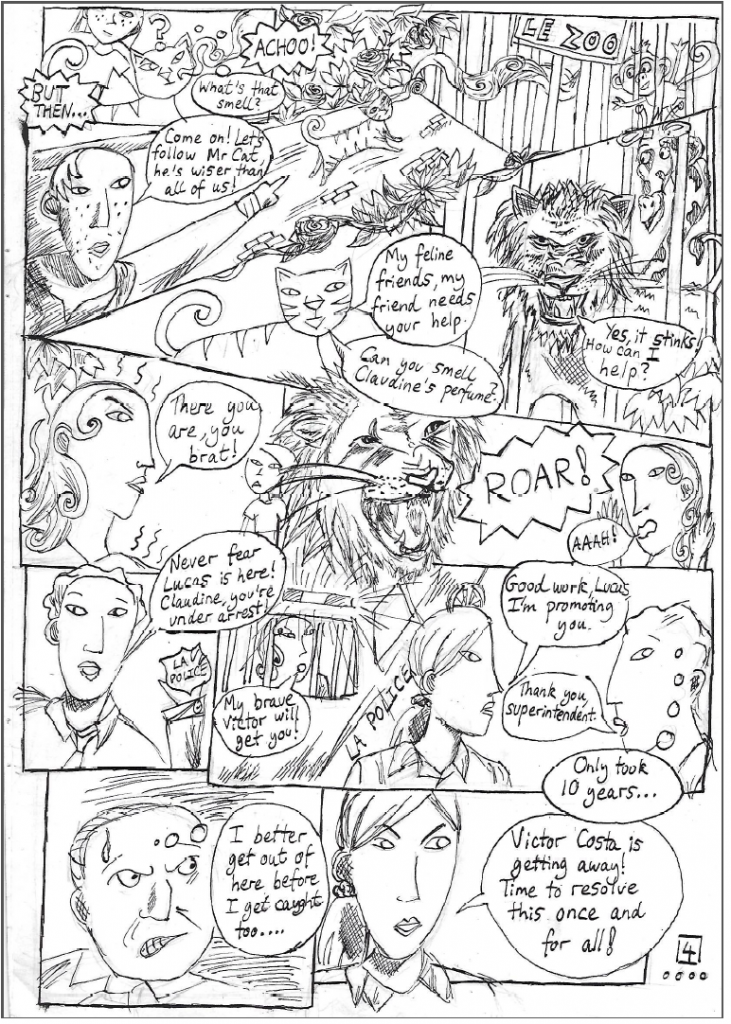

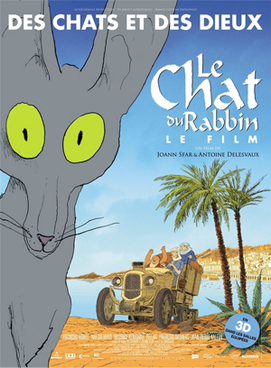

- Le chat du rabbin (2011) – this animated film is based on a series of comics by Joann Sfar; its protagonist is a rabbi’s cat in 1920s Algeria who swallows a parrot and learns how to speak whereupon he is taught the tenets of Judaism by his owner.

Medical dramas

- Thomas Lilti is a French film director and practising doctor. He is known for his trilogy of medical films: Hippocrate (2014) focuses on junior doctors; Médecin de campagne (2016) country doctors and Première Année (2018) medical school students.

Education

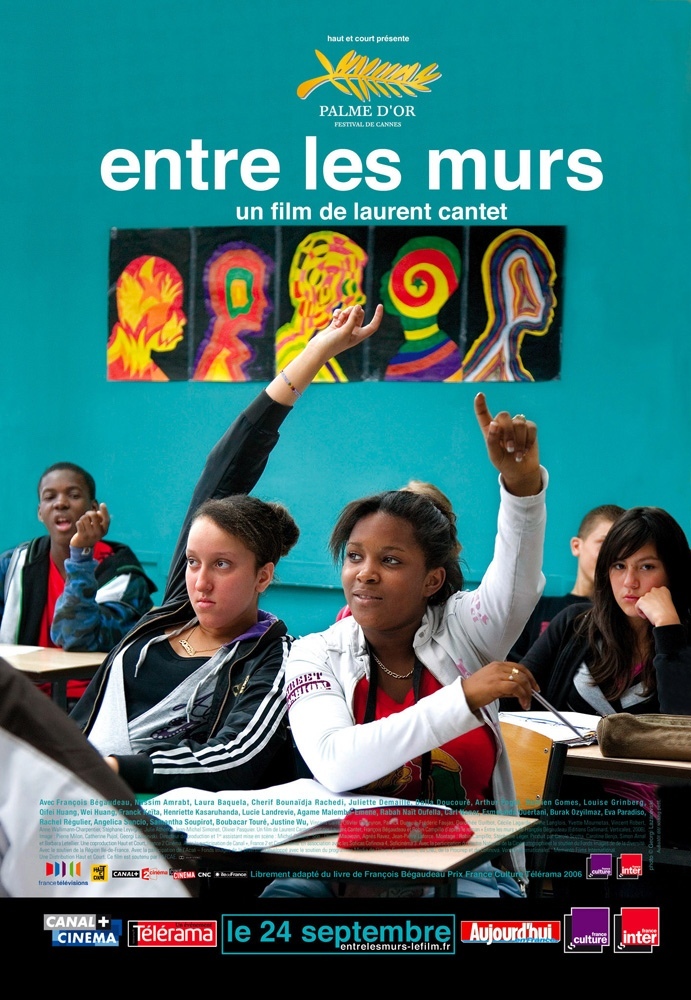

- Entre Les Murs (2008) – set in an inner-city school in Paris, this film is an adaptation of François Bégaudeau’s semi-autobiographical novel of the same name. Bégaudeau stars as a French teacher struggling to deal with his students’ difficult behaviour.

- Avoir et Être (2002) – this documentary looks at the lives of the pupils and teacher at a village school in the French countryside; the school is so small that it only has a single class of children aged four to twelve.

Bon visionnement!

by Ramani Chandramohan

Image credits Wikimedia Commons