posted by Alina Ruiz

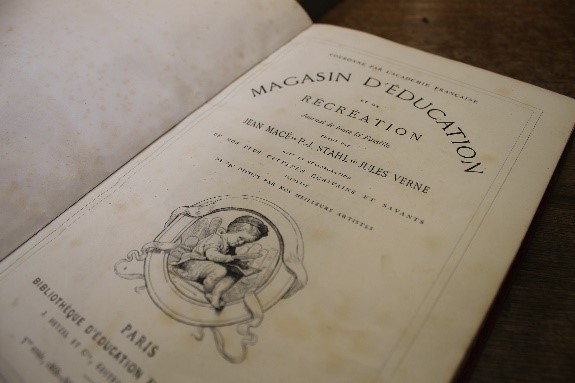

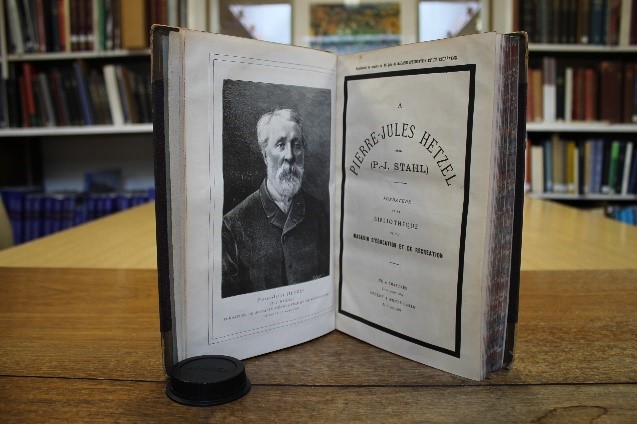

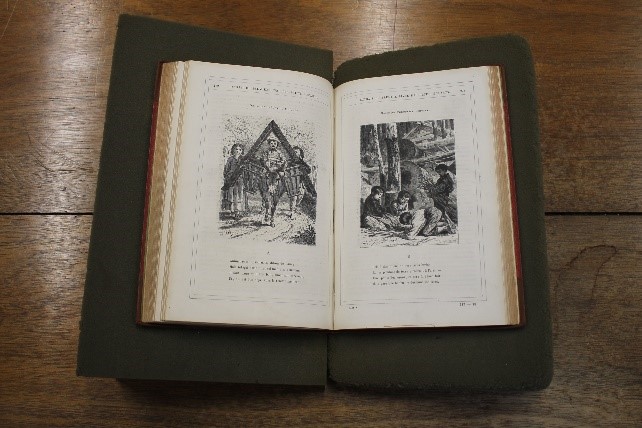

Typical title page of the Magasin d’éducation et de recreation, the era’s most popular children’s periodical. Typical title page of the Magasin d’éducation et de recreation, the era’s most popular children’s periodical. |

What kind of books defined your childhood? In Canada where I’m from, it was all about Robert Munsch, but I personally also enjoyed Franklin, Horrible Harry, Goosebumps, Where the Sidewalk Ends, and of course Harry Potter. When you’re a Master’s student in literature at university, you can feel nostalgic about your childhood reading practices; mostly the fact that you didn’t feel compelled to analyse every passage until all pleasure was lost from reading! Remember when going to the library was part of the class schedule in elementary school and for literally two hours a week the librarian would read to you? Yes, you didn’t even have to read the books yourself! Those were the days!

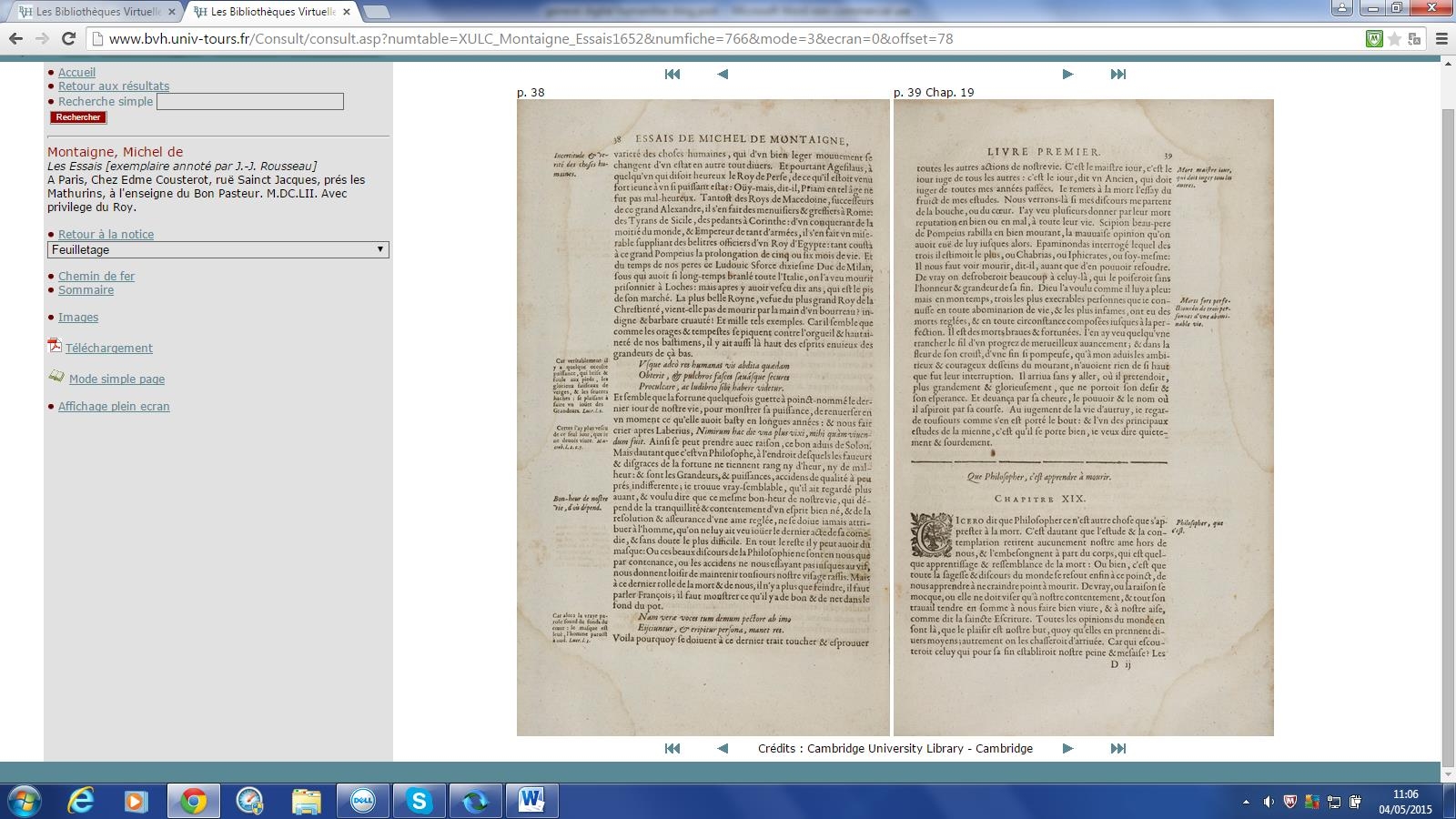

Fast forward to 2016, and yours truly needed to find a nifty topic for her History of the Book project. I combined my nostalgia with my period of specialization and BAM! the topic ‘Children’s Literature in the Nineteenth Century’ was born. It was a good thing I’m a nineteenth century enthusiast, because as I conducted my research, I found out that Children’s literature didn’t even exist prior to this period. ‘But how is this possible,’ you ask? Surely kids were reading before then? The answer is yes – but they were reading books that were originally destined for adults! Even the Fables by Lafontaine were written for adults (if you ever get a chance to read Émile by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, he goes on quite the spiel about how inappropriate it is for children to read the Fables).

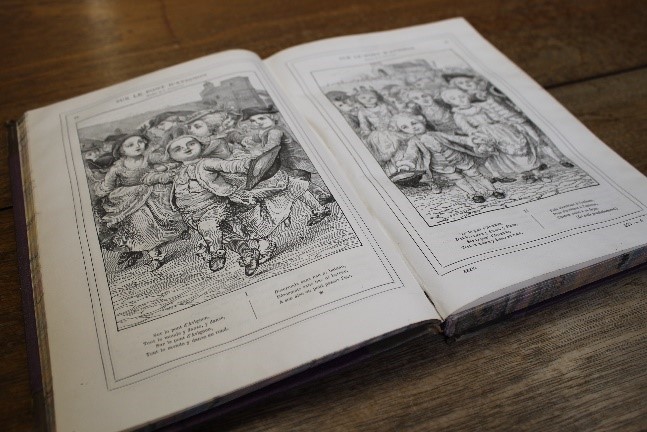

Remember this song from when you were a kid? They were teaching it in the 19th century too! Remember this song from when you were a kid? They were teaching it in the 19th century too! |

At the end of the eighteenth century, the literature available to children ranged from school books dealing with arithmetic, grammar and history, didactic short stories and dialogues written by (mostly) governesses, or whatever kids could find in their parent’s library (they took a strong liking to Robinson Crusoe). Among the literary circles of high society, it was generally accepted that children were not worth writing for. Furthermore, those authors that did write stories for children were not considered ‘real’ writers, and were often ridiculed for their incompetence or shunned from literary gatherings.

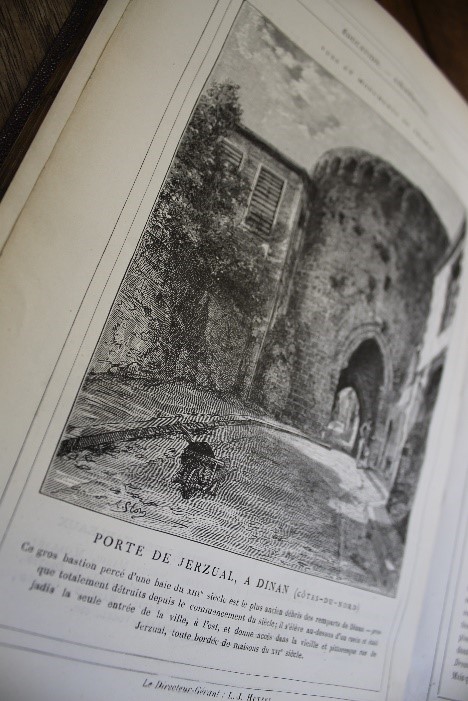

Learn about France’s heritage in this segment called ‘Vues et monuments de France’. Learn about France’s heritage in this segment called ‘Vues et monuments de France’. |

Two things happened in the nineteenth century that were to change the way people perceived children and writing. Firstly, the literacy rate amongst the young was skyrocketing due to the introduction of new education laws that established new schools, subsidized the costs of supplies, secularized the curriculum and introduced mandatory attendance. Children suddenly became thirsty for new books, and publishers took the opportunity to monetize on the phenomenon. This brings us to point number two: industrialization. Thanks to inventions of new presses and cheap paper, books could now be mass-produced at lower costs. A new network of railways made transporting these inexpensive books to eager children all over France much easier and sooner than later, books for children were the era’s top bestsellers.

Issue in memorial to P.-J. Hetzel, following the editor’s death. |

During my research, I kept coming across the name of one specific publisher, Pierre-Jules Hetzel. Out of all the publishers specializing in children’s book, he stood out for me due to his respect, genuineness, and compassion for his audience. Remember how I said that children’s authors were perceived as ‘inferior’ to other writers? Hetzel worked very hard to change that consensus in France. As a publisher of books destined for adults as well, Hetzel commissioned some of the greatest writers of the period to write children’s stories for his first magazine: Nouveau magasin des enfants. Surely you’ve heard of George Sand, Alfred de Musset, and Balzac, but did you know that they wrote stories for children too? Yup! And it may have never happened without Hetzel’s determination to change the face of children’s literature in France.

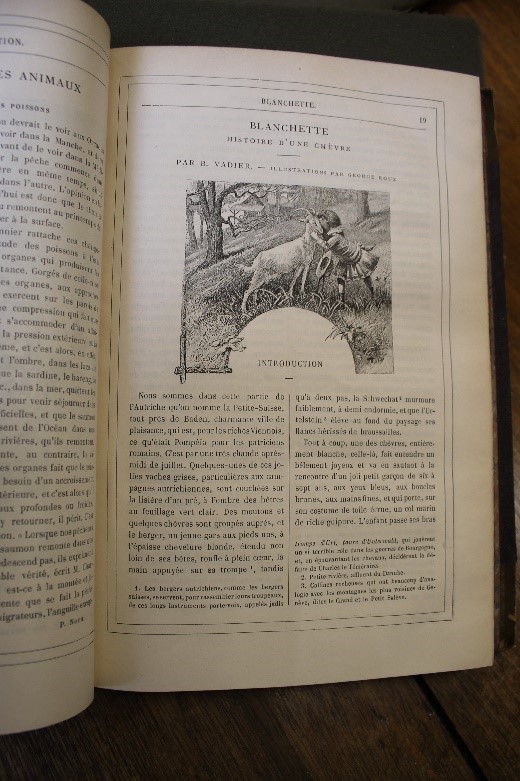

Notice the footnotes designed to help the young readers with new vocabulary. Notice the footnotes designed to help the young readers with new vocabulary. |

Hetzel was a fascinating man and I encourage you to read about his life. For the purpose of my study, I concentrated on what is arguably his greatest accomplishment as an editor: the Magasin d’éducation et de récréation. The title says it all: Hetzel wanted to create a publication that would combine practical information with entertainment. He wanted it to be a high quality project written by renowned authors and academics, and illustrated by the best artists in France. It is important to note that while children’s literature was expanding as a genre, most publishers were purely profit-driven, using the smallest fonts, the cheapest paper and certainly not spending the money to commission illustrations. But not Hetzel. He felt that children deserved better and would be more inclined to learn if you gave them quality material. The paper he used was thick and glossy. The size of his books was large in-8o and hundreds of pictures were featured in each volume. Hetzel’s books were literally works of art.

So what could you read about in this magazine, you ask? Literally everything regarding the arts and sciences. Top academics from the nation’s most reputable schools were invited to contribute factual articles and entertaining fiction. Over the course of nearly forty years of existence, the Magasin included numerous topics including architecture, astronomy, anatomy, geography, family life, history, chemistry, folklore, charity, poetry… you name it! One thing you wouldn’t find, however, was detailed discussion about God and religion. This was demonstrative of Hetzel’s republican values, and his promotion of a secularized society long before the Ferry Laws made it common practice. Another unique aspect of this magazine was that it contained content for all reading levels, meaning that the whole family, from newborns to parents, would enjoy and benefit from it. The most successful writer Hetzel discovered was undoubtedly Jules Verne whose scientific novels first appeared in the Magasin in serials before later becoming classics in their own right. Verne was a perfect example of an author who could appeal to both younger and more mature audiences.

Short poems to teach the letters of the alphabet. Can you see the letters hidden in the pictures? |

As you can probably imagine, the Magasin was an immense project that consumed Hetzel until the day he died. But why did he care so much about it? Why did he personally check every manuscript submitted and rework it until he thought it was absolutely perfect? Considering the success of the publication, he probably could have retired early and moved to some exotic, sunny place, right? Well, that was inconceivable for Hetzel. The man was a fervent republican and truly believed in the progress of humanity through literature. He saw that science and knowledge were the avenue through which people would make the world a more comfortable and just place to live in. He also saw that children, if given a good education and taught to respect and help each other, would be the ones capable of bringing real change in the world. Sounds like someone should be giving this man a peace prize!

I’m not sure about you, but to me this magazine seems pretty downright cool! Sometimes I think I was born in the wrong era and fear for my own future kids who will be reading books on tablets! They will never know the joy of unwrapping a beautifully illustrated keepsake book on Christmas day (and actually being happy to receive it) or waiting by the mailbox for the next chapter of a Jules Verne novel. Or maybe you think I’m crazy and just want to surf the internet. Regardless of how you read literature, hopefully this little post has enlightened you on children and their literature in nineteenth century France. Don’t forget to let us know your favourite book from your childhood by leaving a comment!

P.S. If the Magasin d’éducation et de recreation sounds really neat to you, you may wish to check out Volume I available for free online through Google Books. While you’re at it, why not check out the Bodelian Library Special Collections website to find out what other gems of the past are hiding in the basements of Oxford.

Alina Ruiz is a postgraduate student in French at Oxford University. This post was developed from her research into the History of the Book as part of her Masters degree.

!['Les Comedies Facecieuses', by Larivey [Picture 2]](http://bookshelf.mml.ox.ac.uk/wp-uploads/2015/11/Les-Comedies-Facecieuses-by-Larivey-Picture-2.jpg)

![A 1465 woodcut of 'La Farce de maître Pierre Pathelin' [Picture 3]](http://bookshelf.mml.ox.ac.uk/wp-uploads/2015/11/A-1465-woodcut-of-La-Farce-de-maître-Pierre-Pathelin-Picture-3.jpg)

![Catherine de' Medici playing the role of 'Columbine', possibly with the Ganassa troupe (c. 1574) [Picture 4]](http://bookshelf.mml.ox.ac.uk/wp-uploads/2015/11/Catherine-de-Medici-playing-the-role-of-Columbine-possibly-with-the-Ganassa-troupe-c.-1574-Picture-4.jpg)

![The title-page of the first edition of Shakespeare's 'Romeo and Juliet' (1597) [Picture 5]](http://bookshelf.mml.ox.ac.uk/wp-uploads/2015/11/The-title-page-of-the-first-edition-of-Shakespeares-Romeo-and-Juliet-1597-Picture-5.jpg)