Adventures on the Bookshelf is heading off on its summer holidays. Over the next few weeks, we’ll be picking out some recommended reading from our archives to keep you busy on the beach. We’ll be back with new posts from the first Wednesday in September.

![affiche-finale-agathe-212x300 [55473]](http://bookshelf.mml.ox.ac.uk/wp-uploads/2016/05/affiche-finale-agathe-212x300-55473.jpg)

posted by Catriona Seth

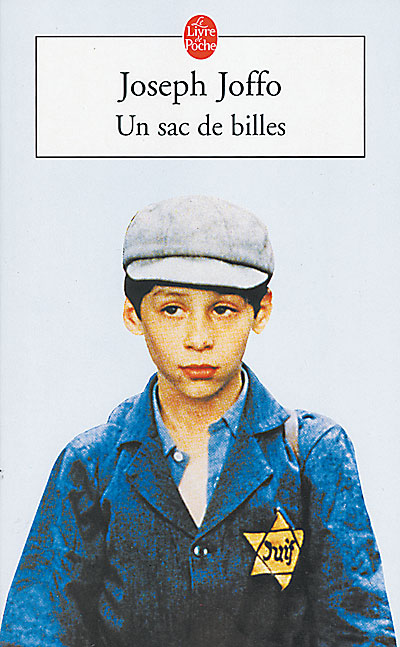

This recommendation comes via the pupils of Culham School. They visited Oxford for a session at the wonderful Maison Française which is a sort of French cultural centre, open to academics, students and the general public. They had spent time working on a recent novel of which I knew nothing, D’Argile et de feu (Of Clay and Fire). They invited the writer, Océane Madelaine, over to talk about her craft. The session at the Maison Française was the culmination of their preparatory work. They were obviously fascinated by the text which involves two characters both called Marie, one of whom lives nowadays and sets out on a long walk towards the South to try and recover from a traumatic experience, that of a huge fire she witnessed. The other is a long-dead potter, Marie Prat, based on the nineteenth-century folk potter Marie Talbot. The modern Marie hurts her foot and takes refuge in an abandoned hut. She discovers the historic Marie’s art and this gives her renewed strength and energy.

Océane Madelaine was born in the Drôme in 1980, read French literature at university and went on to study pottery in a town near Bourges which is where she came across Marie Talbot’s productions. Here is the beginning of the novel:

J’écris les yeux dans le feu, à me cramer les sourcils, le front, les joues. Je regarde et j’écris, chaque mot vient de la braise. Et chaque mot cuit comme ont cuit les pots de Marie Prat dans le four immense du village. Je regarde encore. Autour de moi il fait jour, il fait nuit, la brume de septembre vient, s’en va, revient, je suis au milieu du monde entre nord et sud, au milieu d’une forêt qui m’a donné de l’argile noire et plus encore, je traque les mouvements des flammes douces ou retorses et une chose est sûre : je sais autrement la sauvagerie du feu. Quinze ans durant je l’ai fui, maintenant à mon grand étonnement il brûle à nouveau et c’est moi qui l’alimente, entasse les bûches et enlève les cendres, c’est moi qui fais.

You probably understand most of it.

“Cramer” is a colloquial way of saying to burn. It has the same root as the much formal term “crémation”.

“La braise” is what the French call the embers (it can also be used in the plural—les braises).

“Retors, retorse” is an adjective which means twisted and is often used metaphorically.

“Sauvagerie” is a noun based on the adjective “Sauvage” and is the equivalent of the English term savagery.

“Alimenter” is to feed, and can be used whether you are feeding a fire or a person.

The students’ enthusiasm made me want to read the novel so it is on the top of my pile! And for those who are fluent in French, here is a digest of some of the questions and answers from Océane Madelaine’s Oxford meeting.

Quels sont les trois mots que vous choisiriez pour décrire votre roman ?

C’est une question très dure. Le premier mot ce serait « pieds », le deuxième, « ferveur » et le troisième, « espace ». Ce sont trois mots assez différents.

Pourquoi les pieds et pas la marche ?

Quand on parle des pieds, on parle vraiment du corps. C’est quelque chose qui me tient vraiment à cœur. La marche, c’est l’activité.

Pourquoi la marche est-elle si importante dans votre livre ?

D’Argile et de feu est mon premier roman. Le départ de ce livre, c’est l’envie urgente d’écrire un personnage qui marche. J’ai avancé avec un plan très flou qui s’est affiné et affirmé au cours du travail d’écriture. La chose à laquelle je me raccrochais, c’est cette envie d’écrire un personnage qui marche.

C’est l’histoire de deux cahiers, un blanc, un rouge. L’histoire de la Marie d’aujourd’hui est dans le cahier blanc. La marche est le début du livre. L’autre cahier contient l’histoire de la potière du XIXe siècle, l’autre Marie. Je me suis demandé ce que moi, humblement, je pouvais ajouter à la littérature. J’ai voulu faire la place au cœur même de l’écriture à la sensation. Ce qui m’intéresse, c’est de faire revenir dans l’espace abstrait du langage le corps, la marche.

Quel est le lien entre les deux Marie ?

Les deux Marie sont les deux personnages. J’ai un peu compliqué les choses en leur donnant le même prénom. Le livre est né de l’envie d’écrire sur un personnage qui marche, mais je voulais aussi parler d’une potière du XIXe siècle, Marie Talbot, qui a travaillé en céramique à une époque où c’était un métier d’hommes. Marie Prat est inspirée par le personnage de Marie Talbot dont j’ai vu certaines pièces.

Le lien entre les deux Marie est multiple. Il y a une espèce de filiation. Elles ne se rencontrent qu’à travers les traces. Marie Prat est un personnage fort, une potière, liée à l’argile. Il y a une filiation symbolique, comme si l’une aidait l’autre, sans que ce soit si net. C’est tout ça qui se joue entre les deux Marie. La Marie d’aujourd’hui choisit son héritage. Elle avait au début des souvenirs pesants, très forts, l’incendie. Elle aura l’envie de choisir son héritage, ses souvenirs. On est au niveau symbolique.

Comment les sensations et les éléments interviennent-ils dans le livre ?

Les sensations interviennent de tous les côtés. Il faut que ça circule à partir du corps, vers l’extérieur. Je vois une porosité entre les corps des deux Marie et la forêt. On est dans le personnage et on est dehors. La sensation se situe à l’articulation entre le dehors et le dedans.

Pourquoi vous avez choisi ce titre ? Quel est le lien entre poterie et écriture ?

Parmi les quatre éléments, je suis spontanément attirée par la terre et le feu. L’air et l’eau sont comme des invités. Le titre est venu petit à petit. On a cherché longuement avec mes éditrices. D’Argile et de feu s’est imposé. C’est une histoire de matière. Je voulais laisser la place au corps. J’avais besoin d’accueillir l’argile et le feu qui sont des éléments puissants. Je les connais bien. Je suis céramiste. C’est aussi mon métier. Cela me ressemble bien. Cela ressemble à mon texte. J’appréhende les mots comme je pétris l’argile. Ils deviennent des matières. Dans le texte, la Marie d’aujourd’hui écrit des cahiers. Vers la fin du texte, elle s’adresse à la Marie d’avant : « Je cuis des mots. Il faut qu’ils soient ardents et justes. » Elle met cela en parallèle avec la cuisson des pots par la potière du XIXe siècle.

Pourquoi y a-t-il si peu de ponctuation dans le roman ?

Enlever de la ponctuation me donne une grande liberté dans la phrase. Parfois on ne sait pas qui parle, c’est pour cela qu’il n’y a pas de guillemets. C’est aussi une volonté de laisser de la place au lecteur.

Pourquoi avez-vous choisi d’alterner le présent et les souvenirs ?

C’est une question abyssale. Ce sont aussi des choix. C’est ainsi que les personnages acquièrent une épaisseur. Ils sont dans un présent très fort, mais sont aussi constitués de mémoire, de souvenirs.

Est-ce que vous avez des projets futurs ? Et est-ce que les rencontres avec les lecteurs vous motivent à écrire un deuxième tome ?

Bien sûr, il y a des projets futurs. D’Argile et de feu continue sa route et a pris une certaine autonomie. Cela me laisse la place de me plonger dans un second texte. Pour moi, le travail d’écriture a un rapport assez fort à la solitude. C’est toujours une fête de rencontrer des lecteurs. C’est l’inverse. Ça me nourrit. Un auteur doit amener son texte au plus loin. L’écriture, c’est un artisanat.

Combien est-ce que vous écrivez par jour ? Est-ce que vous écrivez tous les jours ? Est-ce que vous écrivez d’une traite avant de retravailler le texte ?

Chaque écrivain invente sa discipline. Moi le travail d’écriture c’est le matin, souvent tôt, avant la journée d’atelier.

![Pichet Marie Talbot [55474]](http://bookshelf.mml.ox.ac.uk/wp-uploads/2016/05/Pichet-Marie-Talbot-55474.jpg)

***

With thanks to Océane Madelaine, but also to Alexandra, Maud, Clémence, Cassandre, Anaïs, Camille, Pauline, Lucas, Agathe, Jean, Lallie-Rose, Euan, Fanny, Elie-André, Brieuc, Giulia, Nicolas, Tomas, Lydia and their teacher, Céline Martin.

posted by

posted by

![affiche-finale-agathe-212x300 [55473]](http://bookshelf.mml.ox.ac.uk/wp-uploads/2016/05/affiche-finale-agathe-212x300-55473.jpg)

![Pichet Marie Talbot [55474]](http://bookshelf.mml.ox.ac.uk/wp-uploads/2016/05/Pichet-Marie-Talbot-55474.jpg)

posted by

posted by