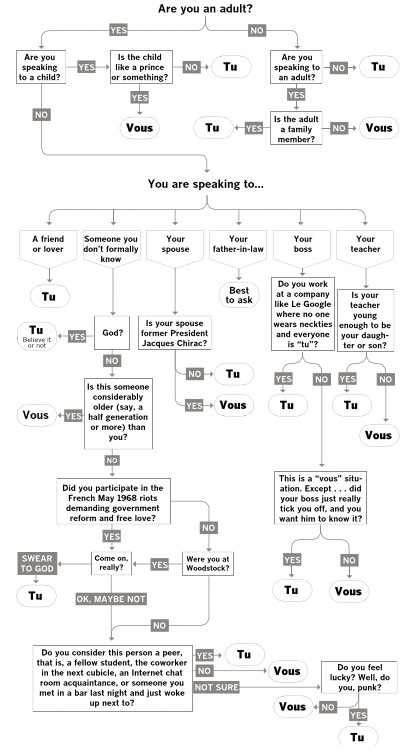

Last week, we offered you a helpful guide towards when you should use tu and when to use vous in conversation with a French speaker. This week, there’s news that these guidelines are falling apart, social chaos is breaking out, and it’s all the fault of social media. Twitter in particular.

Le Monde, the BBC and the Guardian have all been discussing the issue recently, sparked off by a twitter spat between French journalists. Here’s part of Le Monde’s take on the drama (vocab in bold given below the extract):

Il y a un peu plus d’un an, un utilisateur de Twitter, @peultier, journaliste au Monde.fr, a été mal inspiré : il a tutoyé Laurent Joffrin. Les deux confrères ne se connaissent pas, ne se sont jamais rencontrés. Cette audace formelle s’est déroulée sur Twitter. Il n’est pas rare que deux journalistes se tutoient dès leurs premiers échanges lorsqu’ils se rencontrent en reportage, un tutoiement confraternel en quelque sorte. Sauf que Laurent Joffrin, Laurent Mouchard de son vrai nom, est l’aîné de son interlocuteur, et lui est supérieur dans l’échelle sociale, puisqu’il est patron de la rédaction du Nouvel Observateur.

Franz Durupt, alias @peultier, aurait-il tutoyé son aîné s’il l’avait croisé dans la « vraie vie » ? Sans doute pas. Et son accès d’audace virtuelle n’avait pas plu à Laurent Joffrin, peu séduit par ce décalage entre les bonnes manières et les usages en vogue sur les réseaux sociaux : « Qui vous autorise à me tutoyer ? »avait rétorqué le patron du Nouvel Obs à l’impudent, sur une tonalité« volontairement balladurienne », a-t-il expliqué plus tard.

être mal inspiré: have a bad idea

le confrère: colleague, fellow (journalist); the adjective ‘confraternel’ (‘between colleagues’) comes up later

l’aîné de: older than

l’échelle sociale: the social scale

patron de la rédaction: editor-in-chief

croiser qqn: run into someone, come across someone

son accès d’audace virtuelle: his fit of virtual daring

le décalage: gap, mismatch

le réseau social: social media

rétorquer: retort

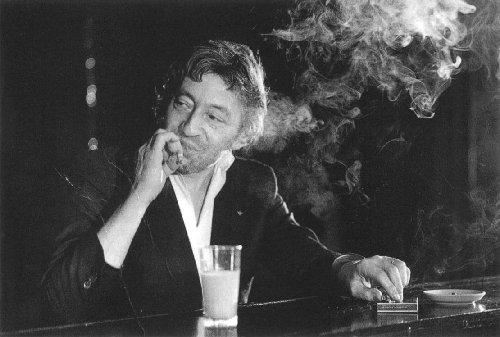

balladurien: reminiscent of former Prime Minister, Édouard Balladur (here, haughty and dignified)

The BBC explores the social niceties involved in online communication in French in a bit more detail. Here’s an extract:

The informal version of “you” in the French language – “tu” – seems to be taking over on social media, at the expense of the formal “vous”. As in many countries, online modes of address in French are more relaxed than in face-to-face encounters. But will this have a permanent effect on the French language?

Anthony Besson calls most people “vous”. As a young man, it is a sign of respect to those older than him, and he’s often meeting new people through his work in PR in Paris.

Yet this all changes on social media. “I always use ‘tu’ on Twitter,” Besson says. “And not just because it takes up fewer of the 140 characters!”

Lots of other French people do exactly the same.

“Tu” is normally for family and friends, but when you’re communicating through @ symbols, joining networks and tweeting under a pseudonym, a formal “vous” can seem out of place, even to someone you’ve never met.

“In the philosophy of the internet, we are among peers, equal, without social distinction, whatever your age, gender, income or status in real life,” Besson says.

Addressing someone as “vous” – or expecting to be addressed as “vous” – on the other hand, implies hierarchy.

It’s too early to say whether Twitter will change how French people talk in everyday life.

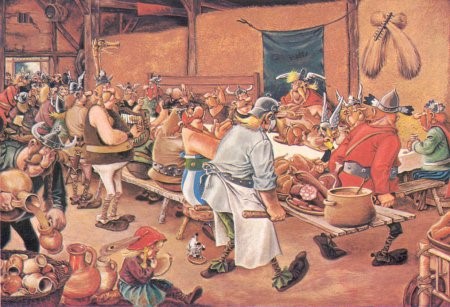

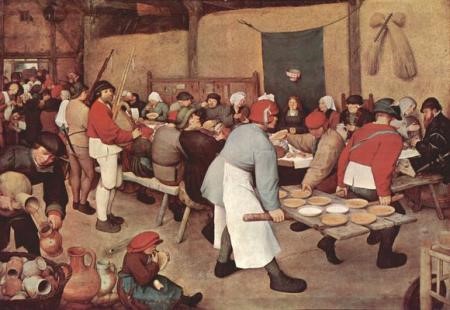

Historically, the biggest shifts towards “tu” occurred at the time of the French Revolution and during the social upheavals of May 1968.

“People who played an active role in May ’68 pleaded in favour of getting rid of the distance created by ‘vous’ and doing away with hierarchy,” says Prof Bert Peeters, of the French and Francophone Studies department at Macquarie University in Australia, co-editor, of Tu ou vous: l’embarras du choix – Tu or vous: an awkward choice.

“However, as they grew up and became mature adults, they realised that having just ‘tu’ in French was not adequate, or not part of being French, and ‘vous’ started coming back.”

Although “tu” is more common than it was pre-68, strict rules still govern its use.

“You would offend a lot of people if you used ‘tu’ and they didn’t know you. It is difficult to say whether social media will change this,” Peeters says.

“However, if people’s first contact is on social media and they start using ‘tu’, it would be awkward to use ‘vous’ in a different context. Once you start with ‘tu’, it is very hard and very rare to abandon it.”

So, frankly, it’s a social mine-field, especially if you’re tweeting someone from an older generation with more old-fashioned ideas about politeness than you. One thing you can definitely get right, though, is the lovely new French verb, tweeter. Here,, to finish, it is conjugated in all its forms:

Présent: je tweete, tu tweetes, il tweete, nous tweetons, vous tweetez, ils tweetent

Passé composé: j’ai tweeté,tu as tweeté, il a tweeté, nous avons tweeté, vous avez tweeté,ils ont tweeté

Imparfait: je tweetais, tu tweetais, il tweetait, nous tweetions, vous tweetiez, ils tweetaient

Plus-que-parfait: j’avais tweeté, tu avais tweeté, il avait tweeté, nous avions tweeté, vous aviez tweeté, ils avaient tweeté

Passé simple: je tweetai, tu tweetas, il tweeta, nous tweetâmes, vous tweetâtes,ils tweetèrent

Futur: je tweeterai, tu tweeteras, il tweetera, nous tweeterons, vous tweeterez, ils tweeteront

Subjonctif: que je tweete, que tu tweetes, qu’il tweete, que nous tweetions, que vous tweetiez, qu’ils tweetent