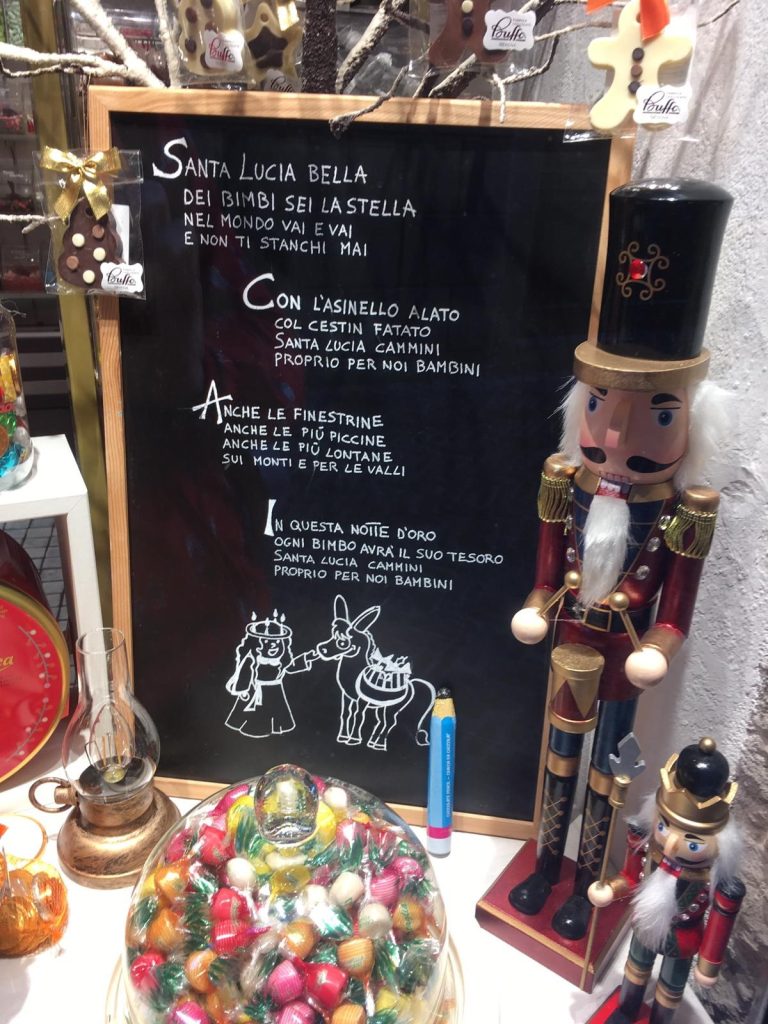

Rather than racing to get their cards in the post in time for Christmas, the French more often send Cartes de vœux, literally ‘cards of wishes’. These can be written until January 31 and will typically express the writer’s hope that the recipient might enjoy health, prosperity and happiness in the year which has just started. This tradition goes back a long way as a note from tragic queen Marie Antoinette, who was guillotined in 1793 in Paris at the age of 38, demonstrates.

The brief letter is held in the library at Bergamo (Biblioteca Angelo Mai) and addressed to Giovanni Andrea Archetti (1731-1805), an Italian priest who was made a cardinal in 1784. [1]

Here is a transcription of the letter. Despite the calligraphic flourishes, it is relatively legible as the close-up shows.

Mon Cousin. Je suis si persuadée de votre attachement à ma personne, que je ne doute pas de la sincerité des vœux que vous formés pour ma satisfaction au Commencement de cette Année, les expressions dont vous les accompagnés sont pour moi un motif de plus de vous rassurer de toute l’Estime que je fais de vous. Sur ce je prie Dieu qu’il vous ait mon cousin en sa S[ain]te et digne garde.

écrit à Versailles. Le 31. Janvier 1787.

Marie Antoinette

There are few differences with the way we would write things. An accent is missing on ‘sincérité’, there is a capital on the name of the month (which is now considered incorrect in French) and, more importantly, the polite ‘vous’ forms of first group verbs, ‘former’ and ‘accompagner’ are here spelled with an ‘-és’ ending rather than the ‘ez’ we would expect. You may also have noticed the full stop after ‘31’ which was a way of transforming the cardinal number into an ordinal number (the equivalent of 31st). Whilst the practice has disappeared from modern French usage, you will find it in German. The signature makes it look as though the final ‘e’ of ‘Antoinette’ has been swallowed into the ‘tt’.

If you compare the transcription with the photograph of the whole page, you will observe different things even before you look at the meaning of the message: it is written on a very large sheet of paper of which the text only occupies about one third; there are slits down the side of the sheet; a strange seal hangs off an appended strip of paper; you can spot the handwriting of three different people. What explains these surprising aspects?

Paper was a luxury commodity in 18th-century Europe and there was a lot of re-using of scraps. Here, the choice of a sheet much larger than would be necessary for the length of the text is a clear sign of wealth. Unlike most of the inhabitants of France, the queen did not have to worry about waste or expense. In addition, a large sheet rather than a smaller one honoured the recipient: it meant he was being treated with the respect owed to an eminent person. The strange folds and the slits down the side (by the blue-gloved fingers on the first picture and along the opposite edge), as well as the paper-encrusted seal, show that this missive would have been sent with a removable lock. The sealing wax pressed between two sides of paper to ensure it would not get broken is on the strip which served as a lock. This was part of a ceremonial practice again intended to make the document seem important but without including a proper seal. Because of the lack of confidential information on the one hand, but also the important diplomatic value of a letter from the queen of France, a particular closing process was adopted. It allowed for the missive to be opened without breaking the seal—rather like when we tuck the flap in to an envelope rather than sticking it down. The French refer to a seal which does not have to be broken for the letter to be opened as a ‘cachet volant’ or ‘flying seal’. You can discover how it would have been prepared in an excellent video about a similar letter from Marie Antoinette to a different cardinal:

As you will notice if you watch the video, once the single sheet had been folded and sealed, it would have looked a bit like a modern envelope with the addressee’s name on it. No street or town address was included because it would have been entrusted to a courier and delivered by hand.

The letter was written by a secretary, almost certainly a man, who had clear bold and ornate handwriting. You can see a change of ink when you get to the signature. Marie Antoinette is the French version of the names Maria Antonia which the future queen of France had been given at her christening in Vienna in 1755. The third person to have intervened also simply signed. This was Jacques Mathieu Augeard, the ‘secrétaire des commandements de la reine’ who was an important court official and would have ensured the letters were duly sent off to the right people. Clearly, this is not a personal letter addressed by Marie Antoinette to cardinal Archetti, but a formal stock message prepared in her name. She may well not even have read the text before it was signed.

What do the contents of the letter tell us? The first thing to note is that the queen calls the cardinal ‘Mon Cousin’. They were not related. This was a conventional courtesy used between people of a certain rank. The missive is clearly an answer to a letter received from Archetti who had sent his own best wishes—it refers to ‘la sincérité des vœux que vous formez’ and ‘les expressions dont vous les accompagnez’ (modernised spelling). It ends with a pious formula hoping that God will watch over the cardinal. The date of 31 January, the last one on which such wishes could be sent, was usual for the royal family. It bears witness to the eminence of the signatory who has not initiated the correspondence but is providing a response.

We are documenting Marie Antoinette’s letters as part of a project with the Château de Versailles’ CRCV research centre. Oxford student Tess Eastgate is one of the participants thanks to her AHRC-funded Oxford-Open-Cambridge Doctoral Training Partnership. Tess is working on weighty political exchanges from the revolutionary period which are quite unlike the message presented here.

To the casual reader, it might seem disappointing to come across a letter like the one to Archetti, with so little personal content, it is in fact very useful for us to have it. It documents the formal relations between the French monarchs and the Catholic hierarchy. It suggests that there may be other similar missives addressed to different dignitaries across the world (examples of ones to cardinals Boncompagni Ludovisi and Borgia have been located) [2] so, if you are anywhere near archive holdings, take a look at what they have. Who knows, you may even come across seasonal greetings to a cardinal from the Queen of France!

Written by Catriona Seth, Marshal Foch Professor of French Literature

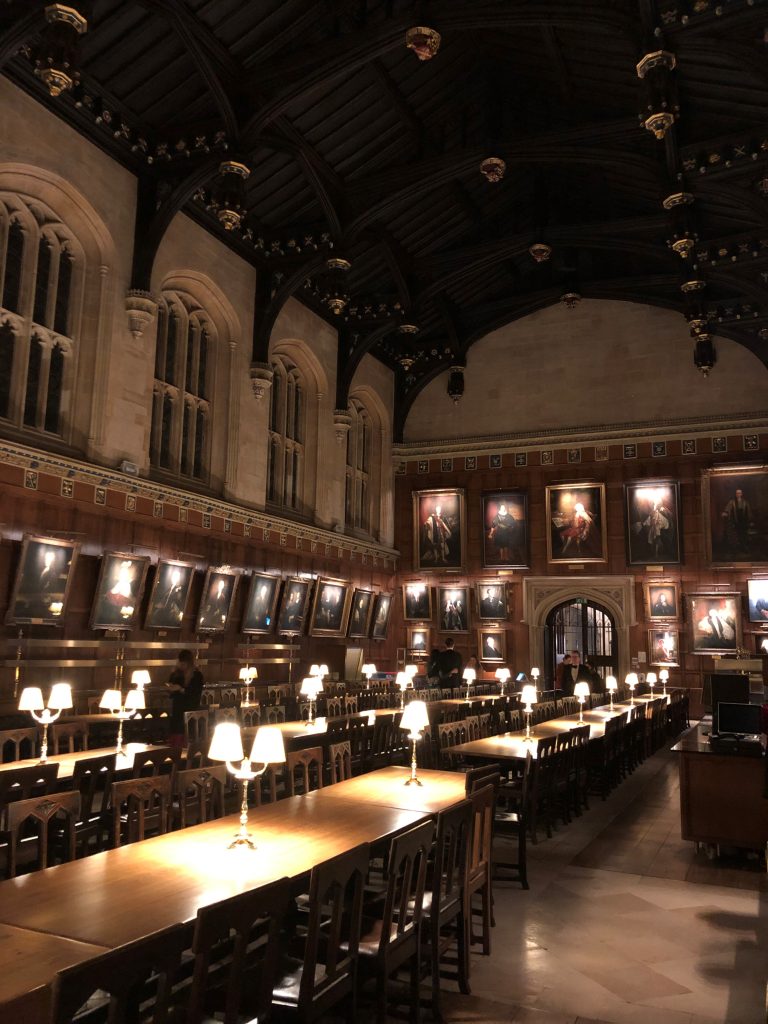

All Souls College, Oxford

[1] Library reference: Autografi MMB 938-945 Faldone A 2) REGINA MARIA ANTONIETTA DI FRANCIA Lettera con firma autografa da Versailles in data 31 gennaio 1787 portante il sigillo reale diretta al Cardinale Archetti (in francese). My thanks to Dottoressa Maria Elisabetta Manca and the staff at the Bibliotheca Angelo Mai.

[2] See https://villaludovisi.org/2022/11/03/new-from-1775-1787-a-revealing-exchange-of-new-years-greetings-by-louis-xvi-marie-antoinette-with-cardinal-ignazio-boncompagni-ludovisi/ (with a 1787 letter which contains many similar terms to the one published here) and https://auktionsverket.com/arkiv/fine-art/rare-books/2016-12-20/150-letter-from-marie-antoinette-to-cardinal-borgia/ [Links accessed on 11 December 2022].