This post originally featured on the Creative Multilingualism blog. It was written by Julie Curtis, Professor of Russian Literature at Oxford and Fellow of Wolfson College. Prof. Curtis is also the Director of Outreach for Medieval and Modern Languages. Here, she reflects on the transformation of a Russian ‘New Drama’ play, Oxygen, by Ivan Vyrypaev, into a UK hip hop version, provoking questions about translation, transformation, and creative ownership.

2002-2018: Ivan Vyrypaev’s play Oxygen, and its 16-year journey between a basement theatre studio in Moscow and a basement rehearsal room at the Birmingham Rep Theatre.

When Ivan Vyrypaev’s play Oxygen was first performed in 2002 at Moscow’s edgiest theatre, Teatr.doc, it caused a sensation. On the one hand it depicted an act of extreme violence – a young man battering his wife to death with a shovel in order to start a new relationship with a woman he believes will offer him more ‘oxygen’ – and it also used aggressively obscene language, transgressing against one of the strongest taboos of Soviet-era theatre. On the other hand, the play had a haunting beauty, deriving from the poetic inventiveness of its use of Biblical motifs, specifically the Ten Commandments, and the musical structuring of the language around refrains, patterning and other compositional devices deriving from both classical and contemporary musical traditions, such as rap.

The play became known as the flagship play of the ‘New Drama’ movement which has arisen in the era of President Putin, and which remains one of the few spheres in which challenges are still offered to official state narratives about society, politics, gender and sexuality, national identity and international relations. It was seen at the theatre by a narrow range of Moscow intellectuals, but gained wider impact within Russia when it was turned by Vyrypaev into a film in 2009; and it also attracted attention internationally – it has been staged in many countries of the world, including a brilliant production (featuring world-champion break-dancers from Russia) staged by the RSC at Stratford in 2009.

Dr Noah Birksted-Breen is a theatre director and Russian scholar who has for many years been exploring contemporary Russian drama and staging it at his London-base Sputnik Theatre. When he joined the Creative Multilingualism team, he attended an event organised by Professor Rajinder Dudrah which brought the grime artists RTKAL, Ky’orion and Royalty from Birmingham to perform on the stage of the Taylor Institution. Their verbal ingenuity, the Rastafarian frame of reference they deployed in their performance, and above all the powerful and infectious rhythms of their art provided a lightbulb moment for me and Noah – we looked at each other, and wondered aloud what would happen if we introduced them to Vyrypaev’s work….

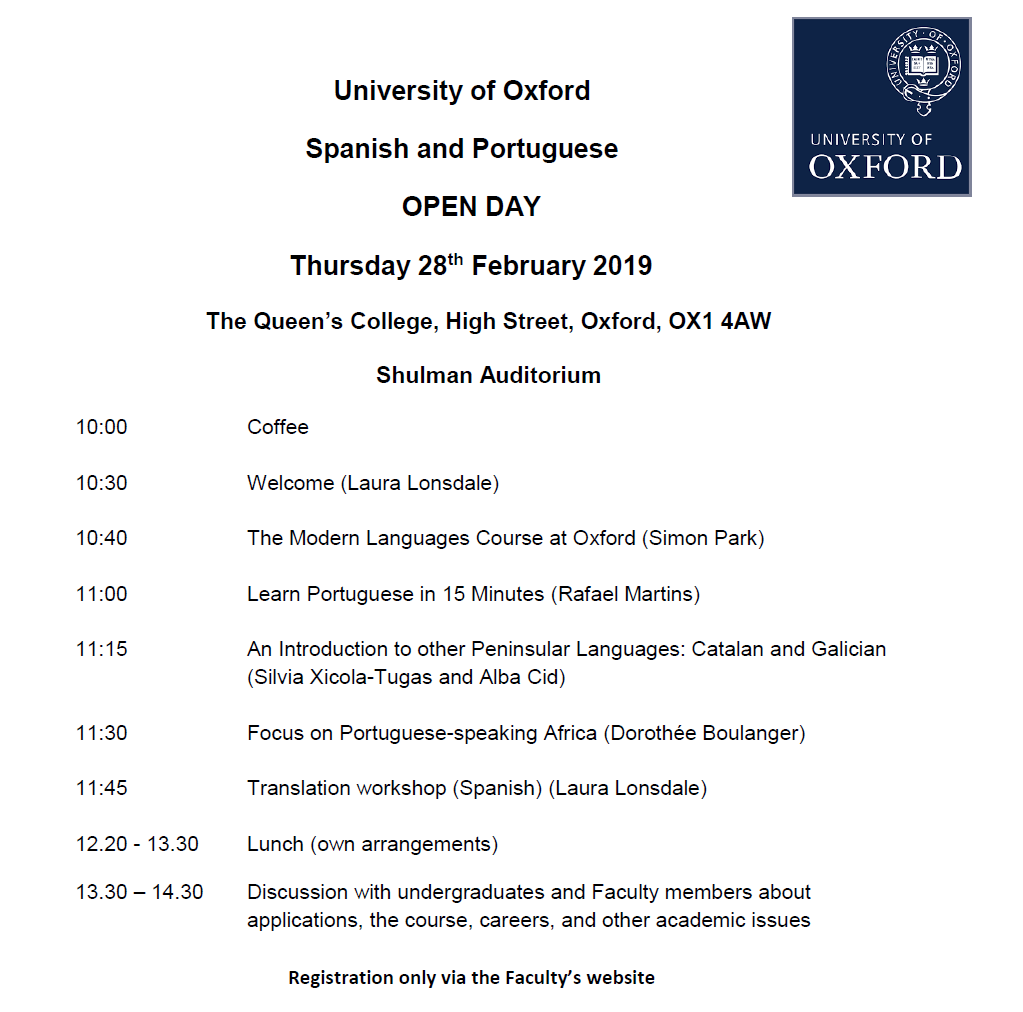

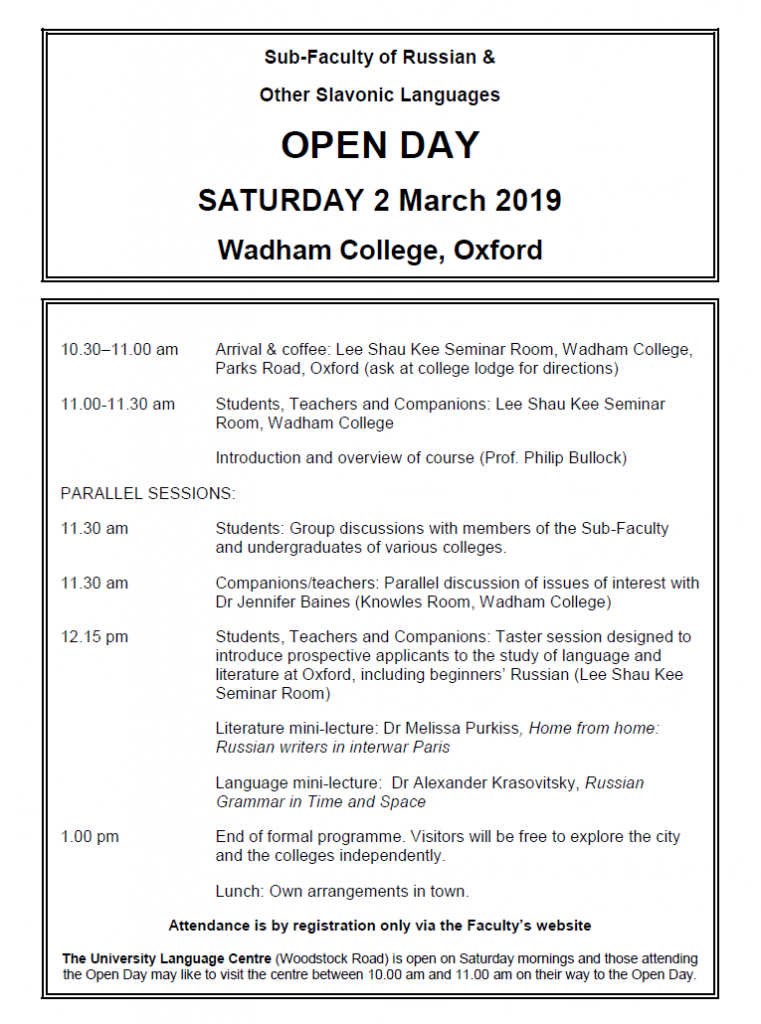

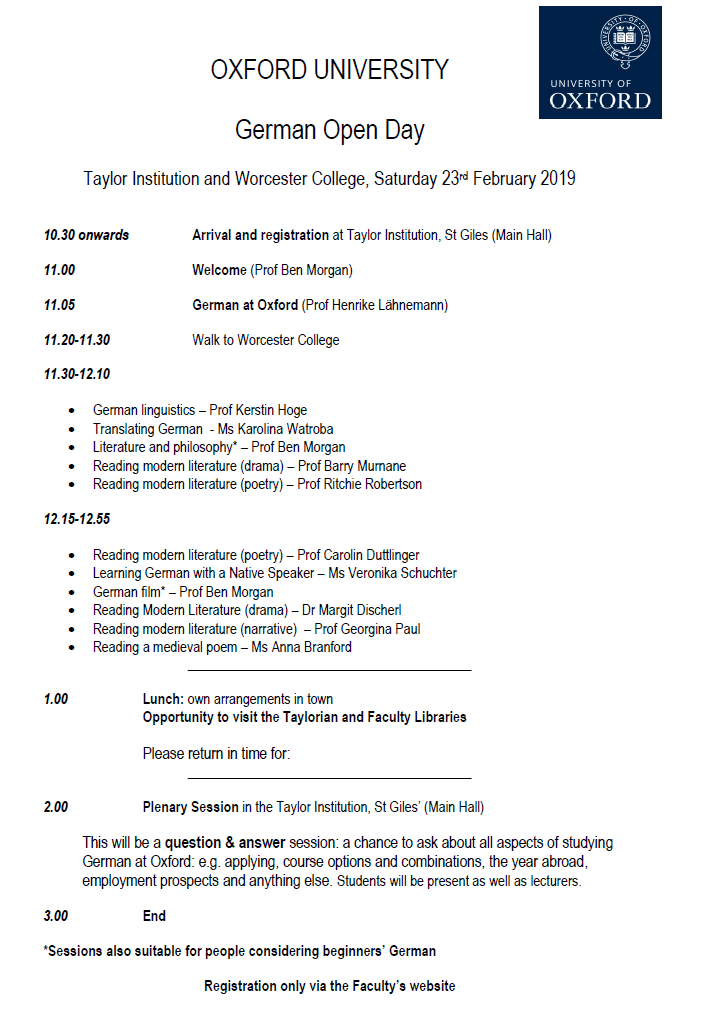

A couple of years later, and that thought has translated into reality, with a performance based on extracts from Vyrypaev’s work being rehearsed in the Birmingham Rep by the brilliant UK rap, hiphop and grime artists Lady Sanity and Stanza Divan, directed by Noah. On Thursday I went along to watch the final research and development session, before the performance later that day curated by Rajinder at Birmingham City University. It prompted all sorts of thoughts in my mind about how issues of ownership and collaboration came together to produce this spectacular meeting of minds across two very different cultures:

- Vyrypaev owns his text, and is very protective about performances of it across the world;

- But Noah is one of the most admired directors of contemporary Russian drama in Britain, so Vyrypaev willingly licensed the text for Noah’s project in Sasha Dugdale’s translation, trusting to both Noah’s knowledge of Russian culture and his artistic gifts to create something which would be both new and true to the original;

- Rajinder knows the rap and hiphop scene in Birmingham via our project partners Punch Records also from the city, and together they recruited artists who would bring their talents to bear on very unfamiliar material, originating from an entirely alien society;

- Once Lady Sanity and Stanza Divan got to know the text, they worked with Noah on how to make it their own, retaining the skeleton of the piece and certain elements of the refrains, playing with the ideas of the male and female characters with the same name – the two Sashas became the two Jordans…

- Lady Sanity and Stanza Divan have focused less on the violence and the obscenity, but have translated the relationship between the two to fit into the witty ‘clashing’ routines typical of rap/hiphop/grime performances; this allows them to develop a gendered rivalry which is absent from the original, with Stanza Divan using sarcasm (‘Calm down!..’ – to use a phrase typical of some male politicians…) to scorn and disparage the sharp-tongued teasing of Lady Sanity;

- But they retain the relative social positions of the two Russian protagonists; she more educated, and from a more comfortable, secure background, he instead from a disadvantaged, broken family and dropping out of secondary education;

- And above all they retain the message of the final section of Vyrypaev’s original, concerning the difficulties faced by the young in today’s world, where so many threats loom;

- Did their UK hiphop theatre work absorb Vyrypaev into their British world? Or did Vyrypaev lead Birmingham’s hiphop performers into new areas? Above all, they said, they recognised that elements in the text of the original were primarily about the freedom of self-expression, and that chimed in with the same preoccupation in British hip-hop and grime art.

- The generosity of very many different people’s collaborations brought this work of art into being: but who ‘owns’ the creative result? Is cultural transposition different from translation?

Watch the below film to find out more about the hip hop theatre version of the Russian play Oxygen.