In this second post in a series by some of the Oxford students who were involved in the judging of this year’s Choix Goncourt UK, Hannah Hodges (French and German, Hertford College) shares her thoughts on the winning book.

Is patience always a virtue? Or are there times when impatience gives us strength?

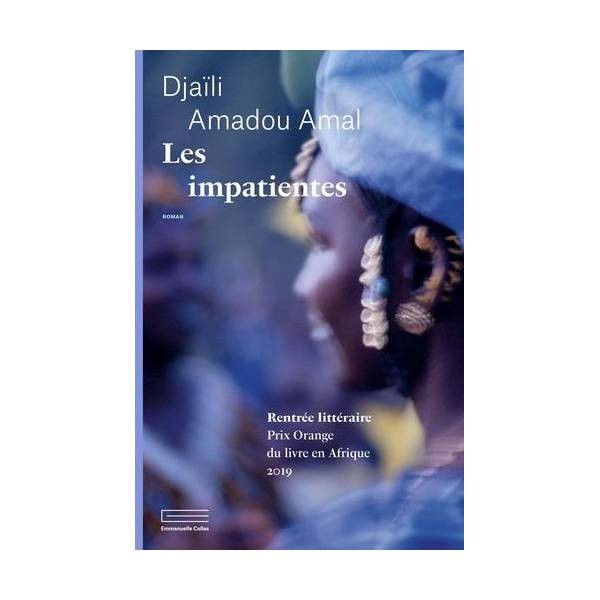

Djaïli Amadou Amal’s novel Les impatientes prompts us to think critically about patience as a quality. Divided into three sections, the novel gives us an insight into the lives and struggles of three women: Ramla, Hindou and Safira. Although very different, these women are united in their suffering under society’s misogynous laws and expectations. Each of these women are encouraged (even forced) to be patient: patient through forced marriage, patient through violence and rape, and patient through polygamy. As Ramla, Hindou and Safira recount the violence and difficulties they face as married women in the Sahel, Amal reveals to the reader the ways in which patience has become a synonym for silent endurance. In this novel, which was inspired by real events, Amal narrates the moments these three women become rightfully impatient.

We begin with Ramla’s story. Ramla’s dream is to become a pharmacist. However, she knows that marriage will put a stop this as married women were not allowed to study, so she rejects several marriage proposals in the hope of finishing her school education and continuing on to university. One day, to the surprise of her mother, she accepts a marriage proposal from a man named Aminou—the best friend of her brother Amadou. Aminou and Ramla had hoped to move away together to study at university. Yet, Ramla’s bubble is soon burst when her uncle informs her that she will marry one of the most important men in the area. Ramla has no option to refuse, she must be patient and do what the men in her family demand. The novel opens with a powerful scene in which Ramla leaves the family compound.

On this same day, Ramla’s half-sister is also leaving the family home. Hindou has been forced to marry her cousin Moubarak, a violent man and heavy drinker. We hear Hindou’s story in the second section of the novel. Hindou’s attempts to flee the violence of her husband but her attempts are unsuccessful. Hindou’s story demonstrates the difficulty of being impatient or refusing to accept the cruelties of marriage. Despite her attempts to flee, she is found and taken back to her father where she receives violent punishment. Patience is something that is forced upon Hindou: she cannot escape the oppressive household of Moubarak or the oppressed position of women in the Sahel.

In the third section of the text, we read Safira’s story. Safira was the first (and only) of Alhadji Issa’s wives until his marriage to Ramla. Like the other two protagonists, Safira is also required to be patient and to accept her husband’s new bride – something she struggles to do. Safira’s section of the novel paints a picture of the toxic environment that is created through polygamy. She tries all manner of ways to remove Ramla from the compound. In the end, she succeeds but not without great difficulty. Safira is different to the other women in that she seems attached to her husband. The violence done to Safira stems from the practice of polygamy which throws her into a state of crisis as her position as the only wife of Alhadji is threatened.

Les impatientes is a polyphonic novel. This works particularly well considering Djaïli Amadou Amal’s purpose in writing the text, which seems to be to both emphasise differences in the violence faced by women and also to show that women are united in this struggle. Watching interviews with Amal (including one with Professor Catriona Seth and hosted by the Maison Française, Oxford), one thing that particularly struck me was her insistence that the concerns she raises in Les impatientes are universal, as they relate to the fight for equality between men and women on all continents. This may at first seem surprising, as her novel seems to be anchored very specifically in the culture of the Sahel—Amal describes vividly medicinal practices, cooking, the housing situation in this part of the world. Yet, the novel also demonstrates that even within this one culture, women face different forms of violence and respond differently. Amal gives each of her three female protagonists a distinct voice, but they are also united in a common fight. In this sense, the text encouraged me to think about how the fight for equality for women often means facing different forms of violence and oppression in different places; it is, in its own way, polyphonic.

Choosing the winner of the Choix Goncourt UK this year proved to be particularly tight. Most of the universities were torn between at least two of the nominated texts. However, it was the poignant simplicity, humbling honesty and the enlightening structure of Amal’s writing that meant Les impatientes emerged victorious. Those universities who cast their vote in favour of Les impatientes were not only motivated by Amal’s style which is at once moving and accessible to students whose mother tongue is not French, but also by the political necessity of the novel. In the interview with Professor Seth, Amal speaks of a MeToo movement for the women of the Sahel, a movement which she believes her novel contributes to. More than the characters themselves, it is the novel which is impatient—impatient to grant women a voice in a society which silences them by demanding they be patient. Les impatientes is a powerful reminder of the emancipatory and political potential that writing and literature offers, and this is what made it a worthy winner of the Choix Goncourt UK 2021.

by Hannah Hodges