posted by Emma Beddall, final-year undergraduate student at Somerville College reading French and German

Why French?

French is a fantastic language with a rich associated culture and history and has a strong literary tradition. Not only is it a language spoken by our closest neighbouring country and a number of others, it is also widely spoken around the world by many as a second language.

Why Oxford?

If the course appeals to you, why not Oxford? The French course is different to many other Modern Languages degrees and provides a truly unique academic experience which allows you to gain an insight into another language and its literature.

How is the course structured?

The first year of the course essentially counts as an introduction to a wide-ranging selection of French literature through the set texts, as well as developing language skills such as translation. Second year onwards, you then have the chance to make choices based upon your interests. Third year is generally spent abroad (although there are certain courses, such as French and Arabic in which the year abroad occurs in the second), before returning to Oxford for the fourth and final year of the course.

What makes the Oxford course different?

The French course offered at Oxford is very different to the courses offered in Modern Languages elsewhere. The main difference is that the study of French at Oxford is very literature-focused, whereas other courses tend to have more modules in topics such as politics, film, cultural studies and linguistics. Furthermore, there is the opportunity to study a broad range of literature, including medieval and early modern texts which are infrequently offered for study at undergraduate level at other universities. Although the course is more traditional in nature, there are a wide range of options available and these include modules on European cinema, linguistics and translation, among others.

What if I’ve done no literature?

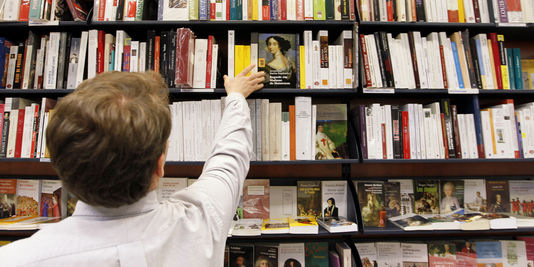

It is not a problem if you haven’t already studied French literature before coming to Oxford, the most important thing is a willingness to study and engage with literature. Everyone arrives having done different things at school, especially given that the range of A-level courses (or their equivalents) tend to focus upon different aspects, some include literature while others, for example, involve studying French films. Furthermore, you may well have previously studied literature in English classes or written essays in various subjects and many of the skills will carry across. I’d also advise trying reading some books in French, and you really don’t have to start off with the imposing classics of French literature, unless you really want to!

Is the course just literature?

No, and we don’t spend all our time just writing essays on literature. Although the course does allow you to study literature in depth and this is an important component of the degree, the course is not solely focused upon literary studies and there is also language component, with oral exams, translation both into and out of French and French cultural studies. Having heard a lot about the literature side of the course before attending Oxford, I was actually surprised by the extent of the language content within the degree.

What if I’m not sure I want to do a year abroad?

The most important thing I can state is that there is time and you do not have to immediately embark on a year abroad. At present, going to university is a big step, especially if you are coming straight out of school, and the very idea of living abroad for a year may seem intimidating. However, after two years of studying, you will likely see things differently and probably feel very different as an individual. The year abroad is an obligatory part of the course, except under specific circumstances, and most people end up loving it and the many experiences it offers. After all, very few other courses give you the chance to spend a year partway through your degree going and doing something completely different of your choosing.

What options are there if I don’t want to do just French?

You can study French as part of a Joint Honours with a number of other subjects. Furthermore, it is also possible to combine French with another language, both European languages and others such as Russian and Arabic. For full details on available course combinations with French, see the prospectus.

Is it okay if I haven’t done any other languages before?

Yes. You can do just French or study French with another subject. However, there is also the chance to start another language from scratch (known as ‘ab initio’) and study it alongside French, if you would like the chance to learn a new language.

Can I study at Oxford with a disability?

Yes, there are many students studying at Oxford with disabilities or long-term health condition. It may be particularly useful to speak to people at the Colleges or the department on an open day if you have any queries. There is also a range of support available, including the Disability Advisory Service for the university, welfare structures within the individual colleges, and the student-organised Oxford Student’s Disability Community (OSDC).

Is the interview scary? How do I prepare?

Think about what you’ve put in your personal statement, especially the books you’ve read and any statements you’ve made about why you want to study French, as these are likely to be the start point of discussion. I actually spent quite a lot of my German interview talking about the Harry Potter series and the challenges it poses for translation. You will likely be nervous beforehand and the interview sounds like a daunting prospect, but try to see it as a chance to discuss things that interest you with another likeminded person; you will likely be surprised by how quickly the time passes!

Does my personal statement have to be full of classic French literature? Should I make my personal statement sound like I’ve read loads of things?

First things first, honesty is always the best policy and if you claim you’ve read things you haven’t, you will potentially get caught out at the interview and this will inevitably be awkward. If you happen to have read some French literature, go ahead and write about it. However, you can also think outside the box, the idea is to show your enthusiasm for the French language, so don’t hesitate to write about your favourite French book, even if it isn’t the most literary of texts, or a French language film or play you’ve seen or how you’ve read the English translation of a classic French work.