This week we continue our series on career profiles. We hear from Daniel Milnes, who studied German and Russian at Somerville College and graduated in 2011. Orginally from Leeds, Daniel now works as a Curator for modern and contemporary art at the Hamburger Bahnhof Museum for Contemporary Art in Berlin. Daniel tells us how his languages have fed into his career path…

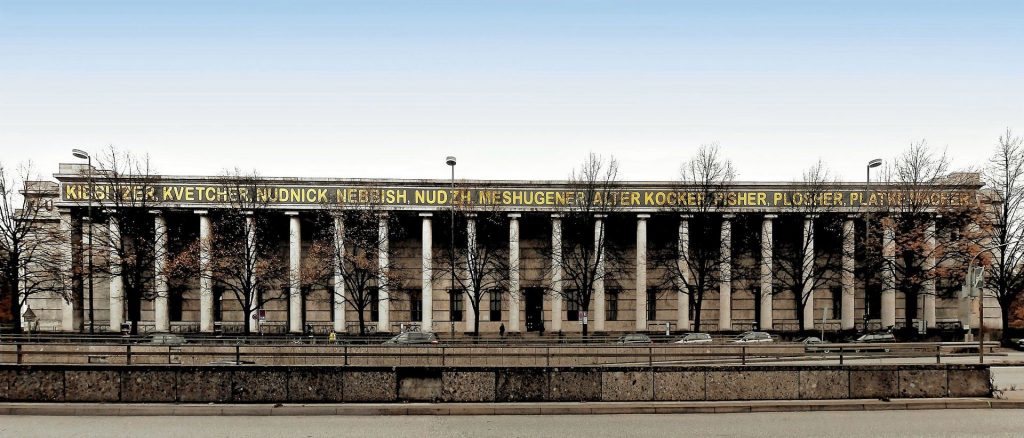

After graduating from Oxford in 2011 I completed a Master’s degree in Art History at the Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg with a research period at the European University at Saint Petersburg (2011-2013). This proved to be the first step toward my current career as a curator for contemporary art. After graduation I completed a two-year traineeship in curatorial practice at the Kunstmuseum in Stuttgart where I served as assistant curator on two large-scale exhibition projects as well as curating my own exhibition with the artist Raphael Sbrzesny. This led to my next position as Assistant Curator at Haus der Kunst, Munich, a leading international institution for the display and discussion of contemporary art and culture.

At Haus der Kunst I served as assistant curator for the project “Postwar: Art between the Pacific and the Atlantic, 1945-1965” which redefined the art historical canon of the postwar period from a multifocal and global perspective, deconstructing the traditional narrative that has until recently been dominated by the work of white male artists from the West. For this project I was responsible for the selection of art from the Soviet Union, liaising with artists, curators, theoreticians, and museum workers in Russia. My contact to the contemporary Russian art world was further strengthened through the development of a solo exhibition with media artist Polina Kanis, who works between Moscow and Amsterdam. In addition, I curated two further exhibition projects which analysed how models of identity have changed since digital forms of mediation have come to dominate daily life.

Since 2018 I am working as Assistant Curator at the Hamburger Bahnhof Museum for Contemporary Art in Berlin, where I am currently organizing the exhibition of the winner of the National Gallery Prize, Agnieszka Polska.

In my day-to-day working life I am constantly travelling and shifting between languages in order to coordinate exhibitions, write academic articles, proofread catalogues, give tours through exhibitions, deliver presentations and speeches, and liaise with artists. This would all be unthinkable without my training in Modern Languages and the sensibility for the nuances of language and culture that it fostered.