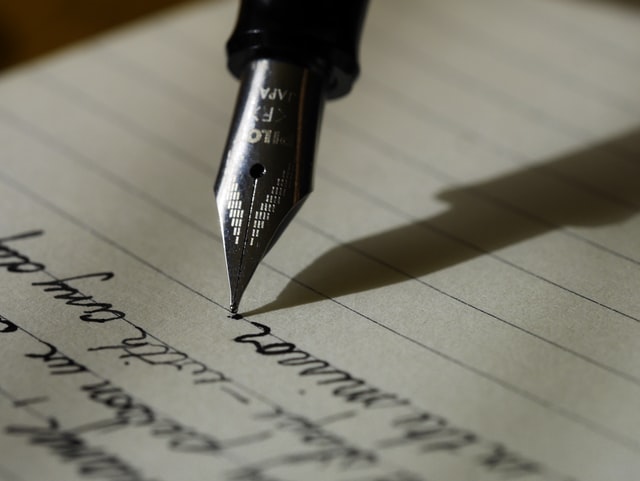

Following the publication of the winning and runner up entries, we are excited to present the highly commended entries for the Year 12-13 category of this year’s French Flash Fiction competition!

A huge well done to all our highly commended entrants! Without further ado, allez, on y va!

****

L’horizon

J’entendais l’horizon dans la voix de ma mère, saisissant le bleu d’un lac sous le ciel blanc : elle était l’immensité entre tout cela. La maison effaçait l’éternité brouillée entre la noyade et l’envol.

Une fois, j’ai vu des rivières coulant sur ses joues. Elle avait pour yeux des fontaines tremblantes qui m’ont fait peur. Plus tard, j’ai appris à craindre les ténèbres et l’inconnu.

C’est d’elle que j’avais appris le mot « fort », et tous les mots pour la peine. Ce jour-là, il n’y en avait aucun.

Aujourd’hui, l’horizon est disparu. C’est trop tard pour des paroles.

– Sophie Shen, Year 12

IEl

« Iel » ai-je dit.

Ce n’est pas offensif, mais il me regarde comme saleté sombre , comme des épées dégoûtants , qui pénètrent son corps propre .

« Vous-Voulez dire…il »

« Non. »

Le silence. J’ai détesté le silence. C’est plus facile d’être silencieux et j’ai souffert des conséquences.

J’ai été ancré par mon propre désir d’être accepté par les gens qui m’accueillent comme un chien. Je voulais encore l’amour; un amour doux qui me mettrait au lit et me tiendrait délicatement.

Il me regarde encore une fois. Ses yeux sont morts; son visage gras et opaque. Qu’est-ce qu’on doit faire pour apparaître vivant dans ses yeux?

– Niall Slack, Year 12

Il est allé loin, trop loin…

Il a demandait au seigneur, “Seigneur, donnez-moi la force pour que je puisse aller loin, loin d’ici.” Il a priait, rêvant d’ une vie où il ne serait embrassé que par sa tranquillité d’esprit. Il aspirait à la sérénité, il aspirait à l’agrément. Le rouge était la couleur qu’il voyait tous les jours, et le noir était la couleur qu’il voyait quand tous les sons autour s’éloignaient. Il voulait voir des arcs-en-ciel, mais à la fin, il n’a vu que de la lumière blanche, et il réalisa qu’il était allé loin, mais trop loin…

– Ishana Sonnar, Year 13

Jamais je n’ai ressenti une joie authentique. Mais, dans un monde où on met les émotions en bouteille et les vend, un jour j’ai découvert un marché clandestin vendant des émotions les plus rares. J’ai trouvé, acheté une fiole de pur bonheur. En sortant, j’ai entendu une conversation choquante: les émotions étaient récoltées de donneurs non-consentants, dont certains ne survivaient au processus. Je dois faire quoi- révéler la vérité, risquant tout, ou me taire, vivant avec la culpabilité? J’ai pris ma décision. Brisant la fiole, je suis partie. Et, ce-moment-là, j’ai ressenti un sentiment libérateur que je n’avais jamais connu.

– Maliha Uddin, Year 13

Avec mes doigts tremblants, je pose le garni finale, une tige de persil, délicatement sur le filet.

«La recette vient de ma grand-mère, j’espère qu’elle te ferait plaisir,” je dis, avec un gros sourire sur mon visage. Ma voix manque d’air car je suis exaspérée par le travail dur de cuisiner. Le plat est symétrique, avec deux demi-cercles de purée de pommes de terre entourant la viande et la sauce au vin de cerise qui s’accumule avec de la myoglobine.

En face de moi, le cadavre en décomposition de mon copain suinte du sang—un biceps decoupee du bras gauche.

– Alexandra Kozlova, Year 12

Tendre la main

‘Prête?’

Je ferme les yeux et j’acquiesce. La partition bruisse dans sa poigne tremblante. Soudain, les touches du piano s’animent. Les années fondent de ses mains fragiles, maintenant se tendant, pleines d’assurance. Je les saisis. Mon saxophone inonde l’air avec nostalgie. Nous échangeons des notes, tissant nos pensées en débat enjoué. Comme le tonnerre et la pluie, nos mélodies fusionnent et avec un apogée, l’orage éclate.

L’enregistrement se termine. Le silence tombe. J’ouvre les yeux pour voir le couvercle du piano toujours fermé. Je tends la main, tremblant comme lui autrefois. J’appuie sur play à nouveau.

‘Prête?’ Non, pas encore.

– Odette Mead, Year 12

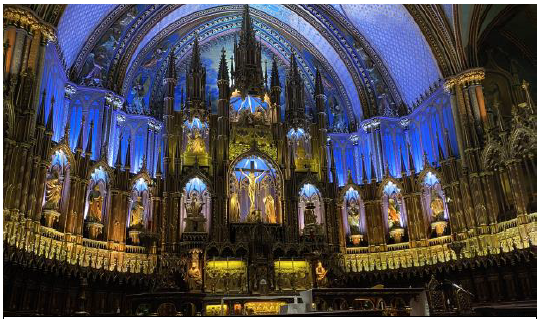

Le Flâneur

C’est moi, le flâneur. C’est moi, que tu vois chaque jour, autour de la ville.

Qui traverse le pont, qui fais le tour du marché, qui rentre dans l’église juste pour en ressortir. Qui dis bonjour au boulanger, à ceux et celle qui passe.

Mais que vois-je ? Je témoins l’antan : les traces de nos empires, nos républiques, nos luttes et nos avances… l’âme incassable de notre ville.

Un jour, je ferais partis de cette histoire. Rien qu’une mémoire, rien qu’un esprit. Mais, un morceau de cette âme, que je ressens avec une telle amour.

– Hugo Sherzer-Facchini, Year 12

Prouvez votre humanité.

Prouvez votre humanité.

Je regarde fixement l’écran de l’ordinateur. Le site me demande de prouver mon humanité, mais comment? Et d’ailleurs, c’est quoi, l’humanité – les guerres ou les principes humanistes? Les deux? Ou bien l’indifférence envers eux?

Frustrée, je passe à un autre onglet qui s’avère être celle du ChatGPT. Je lui ai demandé de terminer mon essai sur la poésie d’Emily Dickinson comme un défi pour son temps. Et c’est exactement ce qu’il a fait, cet outil écrivant plus éloquemment que moi et pourtant pas arrogant; impartial mais pas insensible.

Prouvez votre humanité; non, c’est trop ironique.

– Daria Knurenko, Year 12

****

Félicitations tout le monde!