The Oxford German Network have launched the 12th edition of its annual Olympiad Competition! The competition will run between now and March 2024 with winners being announced in June.

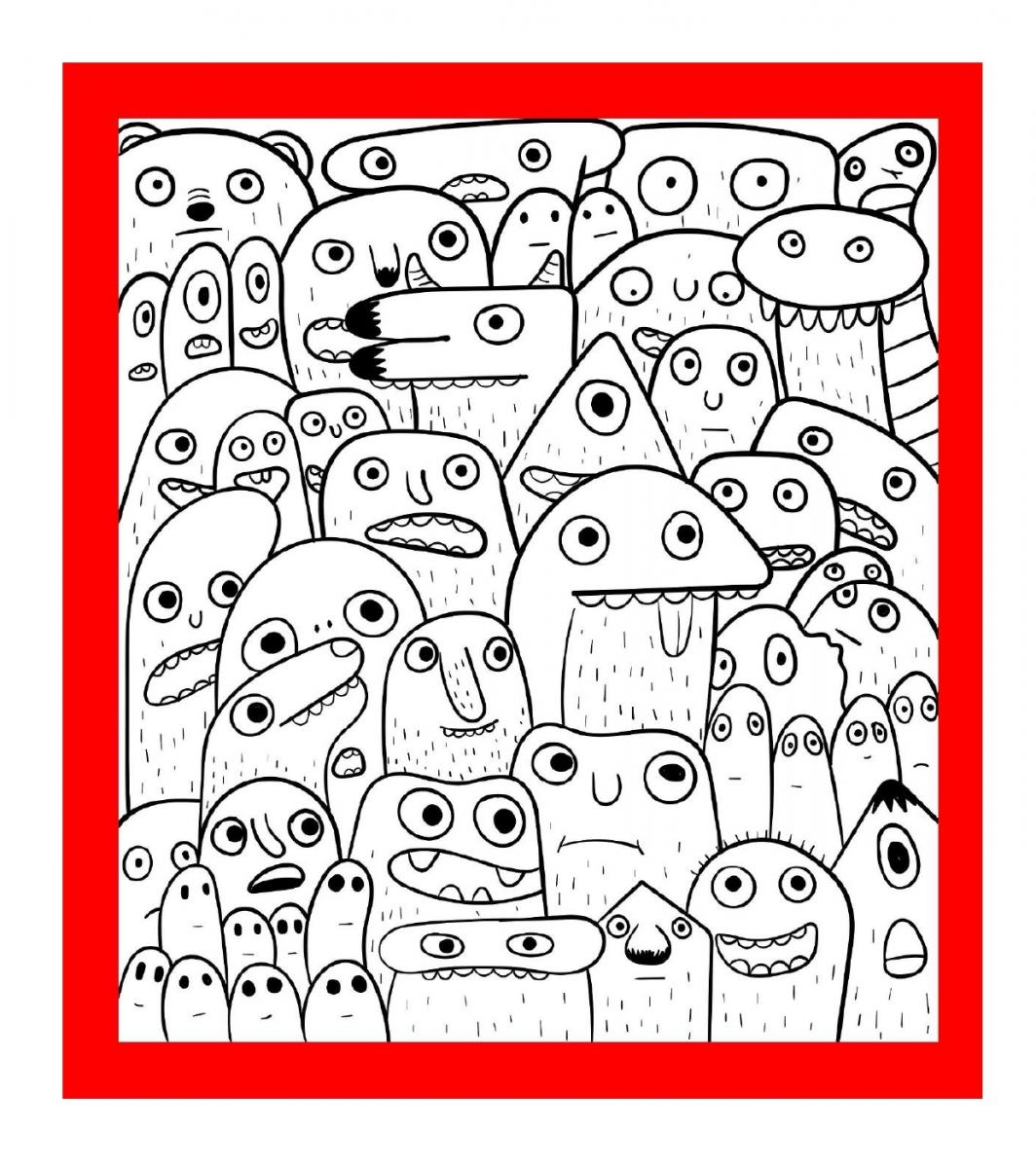

2024 theme: Kafkaesque Kreatures

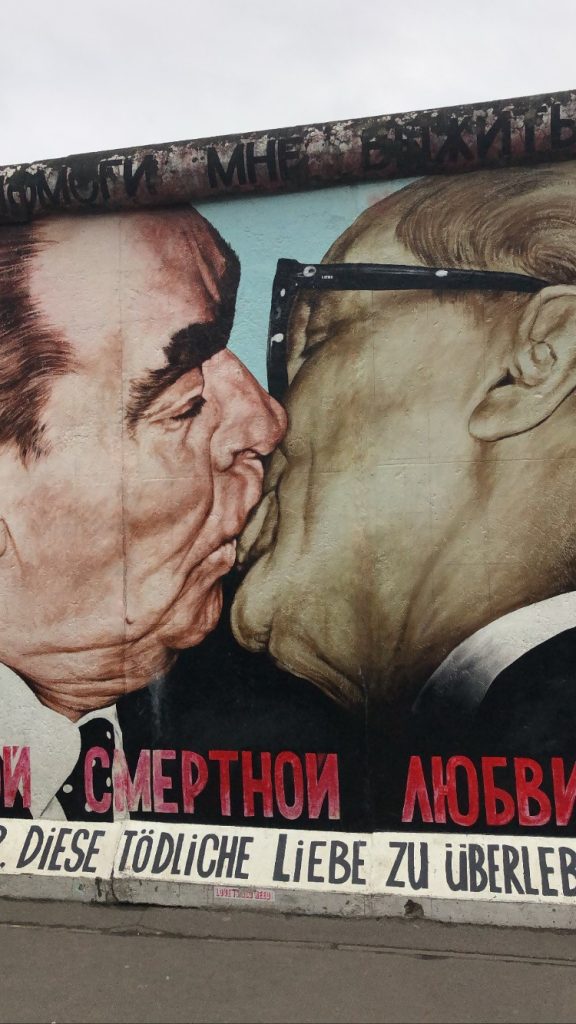

This year’s competition is all about animals – but from perspectives with a difference. The tasks take inspiration from the animal stories by Franz Kafka (1883-1924), who gave the German and English languages the word kafkaesk / Kafkaesque to describe a weird, disturbing experience. Imagine waking up one morning and finding you’ve turned into a beetle. Or that you’re an animal living in a burrow, worrying about your animal enemies up above. But the animal perspectives aren’t all about weirdness – Kafka was a vegetarian. And his story about the ape Rotpeter shows deep concerns about how humans treat animals.

The Competition Tasks

There are a variety of different challenges aimed at pupils in Years 5 and 6 all the way to Years 12 and 13. Some are for individuals to enter, others are aimed at groups. There is even a taster competition for pupils who have never studied German before! From drawing and painting to writing stories and planning conferences, there’s something for everyone! Take a look at the Olympiad website for more details.

You should:

- Choose one of the tasks appropriate for your age group.

- Complete all tasks in German, unless indicated otherwise.

- Refer to the full competition details and guidelines for word count guidance.

Please note:

- All entries must be submitted via the online entry form.

- Each participant may only enter for one task within their age group as an individual entrant. We will only accept group entries (2-4 participants) for the “Open Competition for Groups” category.

- We require a consent form for under-13 participants. Click here to download the form.

Note to teachers: Teachers will be able to submit their students´ entries in bulk. Please contact olympiad@mod-langs.ox.ac.uk for instructions.

Further resources & information

Click here for some thoughts and ideas about this year’s tasks. You can also find the Kafka texts and creatures mentioned in the tasks here.

The closing date for all entries is Thursday, 7 March 2024 at 12 noon.

Results will be announced on the Oxford German Network website in June 2024. Winners will be contacted by e-mail.

Any questions? Please email the OGN Coordinator.